This judgment was handed down remotely at 12 noon on Thursday 8th May 2025 by circulation to the parties or their representatives by e-mail and by release to the National Archives.

.............................

Lord Justice Green:

A. Introduction

The applications

1. The issues before the Court concern the legality of various models of pricing for the sale of generic pharmaceutical drugs to the NHS . The Competition and Markets Authority (“CMA”) issued a decision, running to nearly 650 pages, in which it found that a supplier had abused a dominant position by increasing the price of a generic, long out of patent, drug designed to treat thyroid deficiency to excessive and legally unfair levels in sales to the NHS. Between 2009 and 2017 the price rose from £20 per box to £247 per box. The CMA held that there was no objective justification for these price increases and imposed penalties exceeding £100m. Following an appeal on the merits of that decision to the Competition Appeal Tribunal (“CAT”) a judgment was handed down running to 498 paragraphs dismissing the appeals, save in relation to one narrow point on penalties.

2. The applications before the Court are for permission to appeal from the judgment of the CAT with the appeals to follow immediately if permission is granted. The judgment (“the Judgment”) is dated 8th August 2023 ([2023] CAT 52). This upheld the decision of the CMA dated 29th July 2021 (“the Decision”). This found that, contrary to section 18 Competition Act 1998 (“CA 1998”), a single undertaking, identified as “Advanz”, abused a dominant position from 1st January 2009 to 1st July 2017 (the “Infringement Period”). The Decision is entitled “Excessive and unfair pricing with respect to the supply of liothyronine tablets in the UK”.

The applicants

3. The applications are from the Cinven and Advanz Pharma Corp groups of companies - individually “Cinven” and “Advanz Pharma Corp” and collectively “the applicants” and/or “Advanz”. In the Decision, Advanz was treated as a single “undertaking”. However, at various points in time over the Infringement Period the entities which made up Advanz changed. The CAT (Judgment paragraph [1]) described these changes in the following way:

“…Between 2007 and 2017, a single undertaking consisting of Mercury Pharmaceuticals Limited, Advanz Pharma Services (UK) Limited and Mercury Pharma Group Limited (“the Mercury Pharma Companies”) and, at various points, the Hg Appellant, the Cinven Appellants and Advanz Pharma Corp Limited (“Advanz Pharma Corp”), was the sole supplier of 20mcg liothyronine sodium tablets (“Liothyronine Tablets”) in the UK. This single undertaking as it existed at any particular point is referred to in this Judgment as “Advanz”.”

The penalties

4. The CMA concluded that Advanz made an unlawful profit of over £92.3 million from the infringement, of which:

- £5.7 million dated from the period when Advanz was controlled by HgCapital (“Hg”);

- £34.1 million dated from the period when Advanz was controlled by the Cinven applicants; and

- £52.5 million dated from the period when Advanz was controlled by Advanz Pharma Corp.

5. The CMA imposed a total financial penalty of £101,442,899. It held that Advanz infringed the section 18 prohibition intentionally, or at the least negligently. The CMA divided the penalty between the various entities as follows: (i) Hg was liable for £8.6 million; (ii) Cinven was liable for £51.9 million; and (iii), Advanz Pharma Corp was liable for £40.9 million (after adjustment to prevent the penalty exceeding the statutory maximum).

B. An overview of the case

6. Given the substantial complexity of the facts I set out below an overview of the case.

Liothyronine Tablets

7. The drug in question is Liothyronine. It is used to treat patients with a thyroid hormone deficiency. The majority of patients suffering from hypothyroidism are treated with Levothyroxine which is the frontline drug. Liothyronine tablets are a second line treatment for those patients for whom Levothyroxine is ineffective. The tablets were developed in the UK in the mid-1950s and were sold under the brand name “Tertroxin”. Advanz acquired Tertroxin, which was then long off-patent, in 1992, as part of a portfolio of 22 products acquired by Goldshield Pharmaceuticals Ltd from Medeva plc for a consideration of £1 million. Advanz sold Tertroxin until 2007. The tablets are difficult to manufacture due to the low amount of active pharmaceutical ingredient per tablet and the sensitivity of Liothyronine to minor changes in processing technology. Advanz outsourced manufacture to third-party contract organisations and distribution was outsourced to wholesalers and pre-wholesalers.

Increases in the price of generic Liothyronine

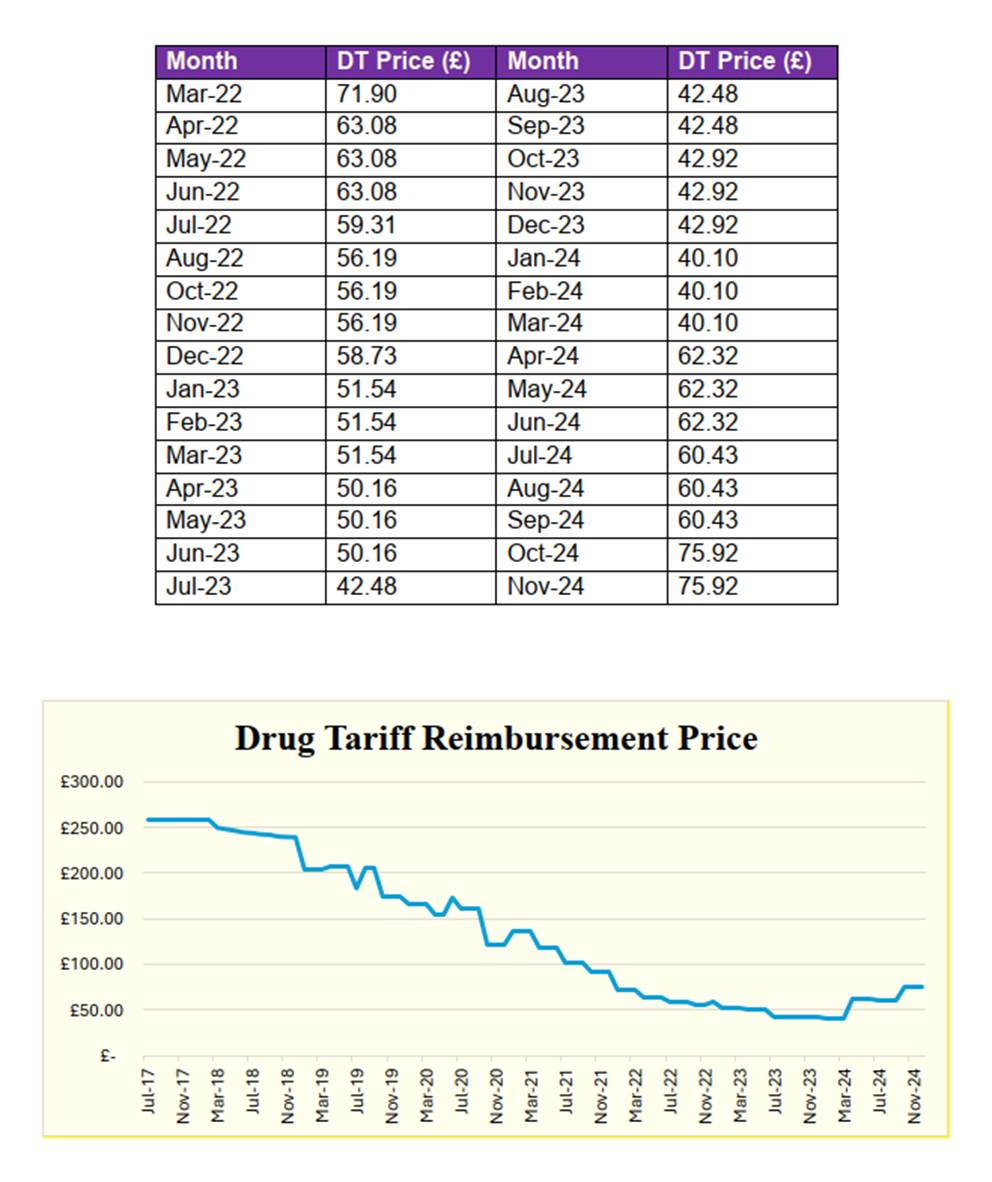

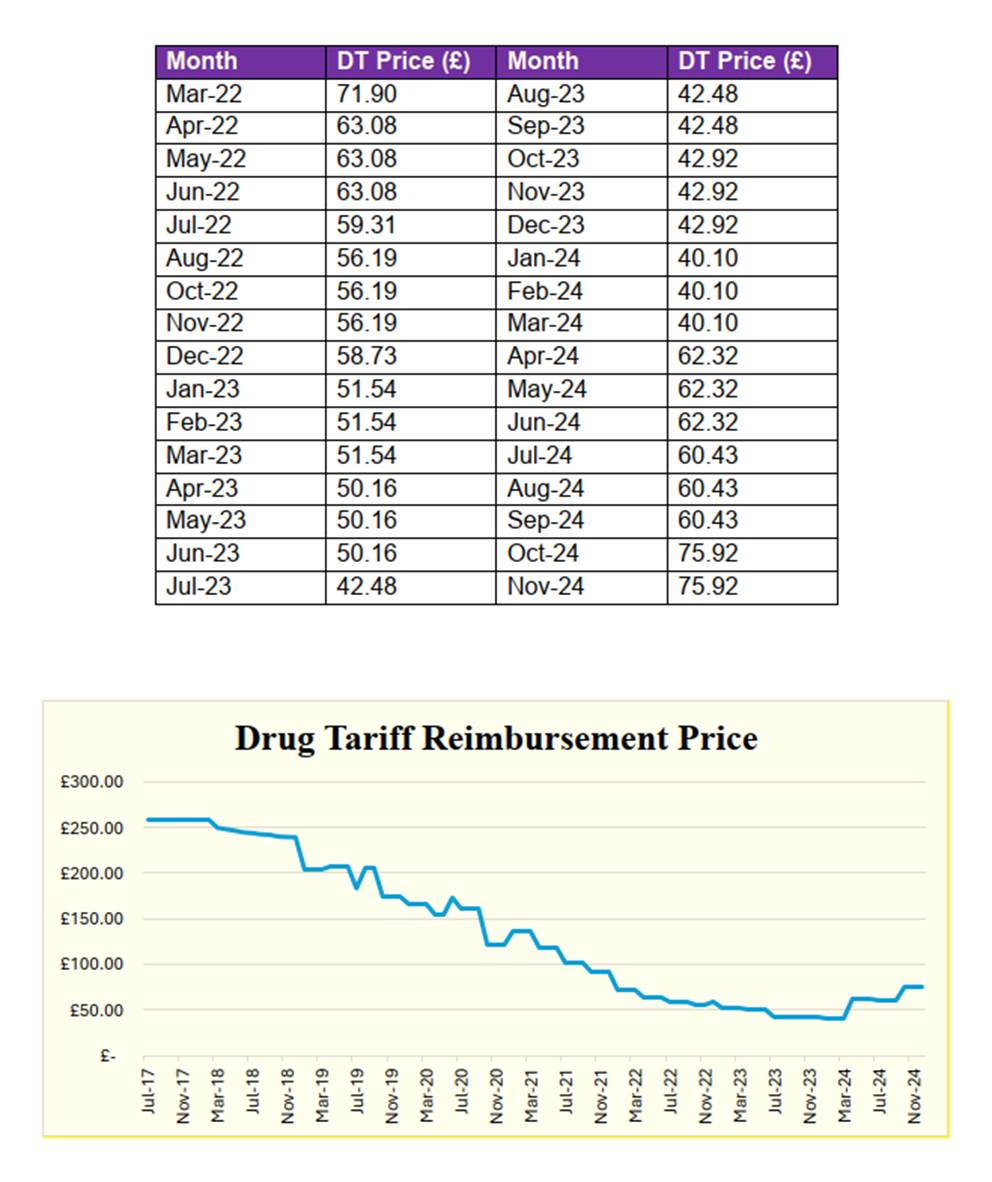

8. The case of the CMA was that, over the Infringement Period, 2009-2017, Advanz abused its dominant position by raising the price for a box of generic Liothyronine tablets to excessive and legally unfair levels. There were 63 progressive price increases across the period. In 2007 a box was being sold at £4.05. By January 2009 the price had increased to £20.48. By August 2012 the price had risen to £46 and by October 2015 to £190. By July 2017 a box was being priced at £247.87. The CMA position was that these price increases were unjustified and were distant outliers when compared against the prices of a range of relevant comparables. In 2017 two companies, Teva and Morningside, entered the market and the price of Liothyronine Tablets fell but not back to the low prices being charged before 2009. In December 2024, at the time of this case, NHS reimbursement prices were at c.£76 per box.

Fairness and Cost Plus

9. The test in law of whether a price charged by a dominant undertaking is abusive and unlawful is fairness, a protean concept the subject of a great deal of case law over the years at both the EU and UK level. There are various methods which can be used to determine what a “fair” price is. In this case the drug in question is long-off patent, there was no requirement for any real innovation, there was a fixed and predictable demand which was highly inelastic and did not go down as prices went up and there were high barriers to entry which served to protect the incumbent dominant undertaking from competition. The CMA considered that the appropriate way to determine a fair price was to apply the “Cost Plus” test. Under this the CMA calculates the cost of production together with a reasonable rate of return on capital. It then compares the resultant cost figure with the average selling price (“ASP”) to see whether the margins charged were excessive and, if so, whether the prices were unfair in themselves or by comparison with other products. It takes into account any considerations that might be relevant to the “value” of the drug.

10. The CMA benchmarked the average Cost Plus figure it had arrived at for the Infringement Period of £4.94 per box against a variety of measures including: Comparable generic drugs referred to in a report on the generics market by economists, Oxera (“the Oxera Report”), prepared for the British Generic Manufacturers Association (“BGMA”) in 2019 and relied upon by the CMA before the CAT ; other drugs in the same category of the Drug Tariff with a similar market volume; NHS reimbursement prices across comparable drugs; and, prices for Levothyroxine tablets. It concluded that Cost Plus was appropriate in the context of these comparables. One especially telling comparator was the price of Liothyronine tablets sold overseas. In Judgment paragraph [73] the CAT found that “Advanz’s prices both during the Infringement Period and after the entry of Morningside and Teva were significantly higher than those prices.” Table 1 to the Judgment set out the details:

Alternatives to Cost Plus: The applicant’s theory of pricing

11. Applying the above process the CAT held that the differentials between Cost Plus and ASP were excessive and unfair in themselves and when measured against comparators. The CAT endorsed the CMA conclusion that the average cost, over the period, was £4.94 per box. The ASP however increased across the Infringement Period from a price close to Cost Plus, to £247. The CAT considered, but rejected, a range of alternative benchmarks put forward by the applicants. Whether the CAT was correct to reject these alternatives is at the heart of this case.

12. The applicants’ case can be summarised as follows. Where the structure of a market is conducive to effective competition regulators and courts should stay out. Judicial comment and economic literature indicate that where barriers to entry are surmountable markets self-rectify because high prices send signals to rivals encouraging new entry; they are a “magnet” drawing rivals into a market and creating competition where none might have existed before. The applicants cite the judicial commentary and the literature as highlighting the difficulties attached to ex-post regulatory enforcement which, it is argued, carries a substantial risk that intervention will cause more harm than good to consumers.

13. The applicants put forward a structural model of what it is argued amounts to a sufficiently effective, workably competitive, market. This comprises 3 conditions: absence of dominance; absence of collusion; and surmountable entry barriers. They contend that as from 2017, after the Infringement Period when new entry occurred, the market was characterised by the existence of these structural conditions. They then advance a series of discrete pricing tests or points which they say reflect the natural outcome of this workably competitive market and, that being so, the prices generated in such markets are necessarily fair and lawful. They say that it is possible to use these price points to extrapolate backwards in time in order to determine a series of benchmarks which can be used to evaluate the fairness of prices actually charged by Advanz during the Infringement Period. These price points are:

(i) Any price emerging from a market where there is no dominance, no collusion, and no insurmountable barrier to entry.

(ii) The price at which new entry is first incentivised.

(iii) The level at which, post new entry, prices settle.

(iv) The price that would be charged in a competitive market (involving multiple suppliers) where each undertaking’s costs would be split over lower market shares than if costs are spread over 100% of volume, with the result that the average cost and price will be higher.

(v) The (high) price actually charged, upon the basis that the resultant high profits can be used to subsidise prices in other product ranges. In the pharmaceutical sector this is said to represent good regulatory practice and be consistent with workable competition.

14. To meet the unhelpful but incontrovertible fact that these benchmark tests lead to much higher prices being treated as fair than Cost Plus, the applicants challenge the very basis of the Cost Plus test. It was said to be unreflective of economic reality and lacking in legal certainty. It was antithetical to good competition law policy because, by its nature, it curbed the charging of high prices which encouraged new entry and the emergence of new competitive market forces. It thereby entrenches market power and dominance. High prices were systemically good for the creation of healthy competition and thereby for consumers; Cost Plus was inimical to the development of new and healthy competition, it protected dominance, and was bad for consumers.

The legal basis for the applicant’s theory of pricing: workable competition

15. The applicants dress this theory in legal clothing by reference to the supposed endorsement in case law of the principle that prices are deemed to be fair, and hence lawful, where they reflect the conditions of “workable competition”. Where evidence of the prices that would be generated in a workably competitive market exists, it is argued that it is wrong in principle for regulators and courts to adopt a Cost Plus test.

16. The applicants contend that this approach is consistent with the test laid down by the Court of Appeal in CMA v Flynn Pharma [2020] EWCA Civ 339 (“Phenytoin”) which pulled together and summarised nearly 50 years’ worth of case law. Two central principles are said to underly the law as summarised in that case:

(i) That the overarching test is whether the dominant undertaking “… reaped trading benefits which it could not have obtained in conditions of normal and sufficiently effective competition i.e. workable competition”: Paragraph [97(i)].

(ii) That regulatory intervention can, perversely, harm the normal process of competition by preventing the emergence of markets that would otherwise self-correct through new entry. The Court in Phenytoin is said to have established the principle that where entry barriers can be overcome (ie are surmountable) markets are self-correcting and intervention risks prolonging a monopoly situation by blocking efficient pricing signals which otherwise promote market entry and the advent of real competition. A belief in the vitality of market forces is bolstered by the well-established high likelihood of regulatory failure in the case of price regulation: Paragraph [104].

The acquiescence issue

17. On a different note, it is also contended that since the prices actually charged during the Infringement Period had been paid by the NHS subject to a system involving drug tariff scrutiny there was legal acquiescence which meant that the prices charged could not be unlawfully unfair and abusive.

The position of the CMA and the CAT on pricing issues

18. In the Decision the CMA rejected all the arguments put forward by the applicants. Before the CAT the applicants adduced new evidence in particular of pricing trends in the period following the Decision and current at the time of the appeal. That evidence addressed the theory of pricing described above. The CAT, taking account of the new evidence, dismissed the appeals and upheld the Decision. In particular it endorsed the CMA’s finding on Cost Plus as an appropriate benchmark for determining a workably competitive and fair price in generic pharmaceutical markets: Judgment paragraph [230] and the conclusions at paragraphs [347]-[350].

The issue about penalties

19. On the appeal to the CAT a portion of the financial penalty imposed by the CMA in the Decision was set aside. That component amounted to a significant increment added by the CMA to the basic penalty to reflect a statutory policy imperative seeking to create what is termed “specific deterrence” i.e. a sum intended to deter repeat offending by the undertaking in question. This is a sum over and above any component of the penalty designed to achieve “general” deterrence which is included as a message to the world at large not to engage in the condemned conduct - pour encourager les autres. The CMA says that the CAT erred when removing the element for specific deterrence because it misconstrued and/or misapplied the relevant statutory guidelines on penalties that it was required to have regard to.

C. The issues arising for determination.

20. A limited number of proposed grounds of appeal were initially before the Court. They evolved in the course of written and oral submissions. The CMA objected but, on balance, the pragmatic course is simply to deal with them. They break down into a series of issues:

Issue I - “Workable competition”: The minimum conditions necessary for a workably competitive market / workability as a bright line test of fairness.

Issue II - EIP: The relevance to fairness of Entry Incentivising Prices (“EIP”).

Issue III - PEP: The relevance to fairness of Post Entry Pricing (“PEP”).

Issue IV - New pricing evidence: The relevance and admissibility of new evidence of PEP sought to be adduced and relied upon by the applicants relating to price movements subsequent to the Judgment of the CAT.

Issue V - MFP: The relevance to fairness of the prices that would have been charged in a competitive market with multiple suppliers needing to recover their fixed costs over lower volumes (“multi-firm pricing” or “MFP”).

Issue VI - Portfolio Pricing: The relevance to fairness of pricing designed to generate high profits in relation to one product which could then be used to subsidise other products (“Portfolio Pricing”).

Issue VII - Acquiescence: The relevance to fairness of the fact that the NHS did not object to pricing subsequently found by the CMA to be abusive.

Issue VIII - The burden and standard of proof: Did the CAT disregard the burden and standard of proof in relation to the pricing issues?

Issue IX - Penalties for specific deterrence: The approach of the CAT when applying the statutory Guidance to the calculation of penalties designed to create a specific deterrent to future repetition or infringement by the undertaking in question.

D. A summary of the relevant law

21. There is no real dispute about the law to be applied. I set out below a summary of: (i) the test of fairness under section 18 CA 1998; (ii) the nature of merits appeals before the CAT; and (iii), the jurisdiction of the Court of Appeal.

The test of fairness under section 18 CA 1998

22. Section 18 (1) CA 1998, entitled “Abuse of dominant position”, provides that any conduct on the part of one or more undertakings which amounts to the abuse of a dominant position in a market is prohibited if it may affect trade within the United Kingdom. Section 18(2) lists various examples of abuse. Section 18(2)(a) stipulates that conduct may amount to an abuse if it consists in:

“… directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions”.

23. There is no statutory definition of fairness in the CA 1998 or in equivalent treaty provisions at EU level. It is common ground that jurisprudence under the EU regime is relevant. At that level the locus classicus of the test of fairness is the judgment of the CJEU in Case C-27/76 United Brands v Commission EU:C:1978:22 (“United Brands”) in particular at paragraphs [248]-[253]. Markets exhibit an almost unlimited array of features and the evidence relevant to establishing abuse is commensurately diverse and variable. The Court in Phenytoin summarised the various approaches to evidence endorsed in case law. The underlying premise, which is reflected in the literature, is that no category or type of evidence is to be treated as necessarily dispositive or relevant, or indeed irrelevant. The guiding principle is weight, not admissibility: Phenytoin paragraphs [97(iii)-(vii)] and [105]. This means that all evidence is capable of being admitted but its value will be for the CMA and CAT, on an appeal, to weigh.

24. The judgment in United Brands, together with nearly 50 years of subsequent jurisprudence, was analysed by the Court of Appeal in Phenytoin (ibid) where at paragraph [97] the Court set out a summary:

“97. …

(i) The basic test for abuse, which is set out in the Chapter II prohibition and in Article 102, is whether the price is “unfair”. In broad terms a price will be unfair when the dominant undertaking has reaped trading benefits which it could not have obtained in conditions of “normal and sufficiently effective competition”, i.e. “workable” competition.

(ii) A price which is “excessive” because it bears no “reasonable” relation to the economic value of the good or service is an example of such an unfair price.

(iii) There is no single method or “way” in which abuse might be established and competition authorities have a margin of manoeuvre or appreciation in deciding which methodology to use and which evidence to rely upon.

(iv) Depending upon the facts and circumstances of the case a competition authority might therefore use one or more of the alternative economic tests which are available. There is however no rule of law requiring competition authorities to use more than one test or method in all cases.

(v) If a Cost-Plus test is applied the competition authority may compare the cost of production with the selling price in order to disclose the profit margin. Then the authority should determine whether the margin is “excessive”. This can be done by comparing the price charged against a benchmark higher than cost such as a reasonable rate of return on sales (ROS) or to some other appropriate benchmark such as return on capital employed (ROCE). When that is performed, and if the price exceeds the selected benchmark, the authority should then compare the price charged against any other factors which might otherwise serve to justify the price charged as fair and not abusive.

(vi) In analysing whether the end price is unfair a competition authority may look at a range of relevant factors including, but not limited to, evidence and data relating to the defendant undertaking itself and/or evidence of comparables drawn from competing products and/or any other relevant comparable, or all of these. There is no fixed list of categories of evidence relevant to unfairness.

(vii) If a competition authority chooses one method (e.g. Cost-Plus) and one body of evidence and the defendant undertaking does not adduce other methods or evidence, the competition authority may proceed to a conclusion upon the basis of that method and evidence alone.

(viii) If an undertaking relies, in its defence, upon other methods or types of evidence to that relied upon by the competition authority then the authority must fairly evaluate it.”

25. The central issues in this case relate to the legal relevance of, and the evidential weight to be attached to, different types of evidence relating to pricing. The applicants argue that the pricing evidence they adduced before the CAT was of such high probative value that it massively outweighed other categories of evidence relied upon by the CAT. A facet of this concerns the burden placed upon undertakings under investigation to raise issues and evidence which then triggers a legal duty on the regulator or court to evaluate that evidence (cf Phenytoin paragraphs [97(vii) and (viii)] above). In the present case this is significant because the CAT found a violation by Advanz on the basis of two categories of evidence (Cost Plus and comparables based upon current pricing) that, according to the settled jurisprudence, suffice in law to establish abuse and in respect of which there is no challenge in this Court. How does the evidential burden on a defendant undertaking operate in such a case?

26. A second issue concerns the extent to which the relevance and weight to be attributed to various types of evidence are affected by legal principle. The applicants have referred to two types of legal principle. The first relates to the principles governing the concept of abuse. The second concerns more general principles of law. In relation to the former (abuse) the applicants say that because of the legal test for abuse particular types of evidence (in particular those they rely upon) constitute mandatory benchmark tests which are dispositive of the outcome. Where such evidence exists, it is unlawful for the decision maker to rely upon other types of evidence. In relation to the latter (general principles) the main example referred to concerns the principle of legal certainty which was relied upon by the applicants to support their argument that certain types of evidence should be accorded greater or lesser weight than other types. For instance, the applicants contend that their evidence of settled prices (in the context of Issue III - PEP) is superior as a test in law in terms of legal certainty to evidence of stabilised prices which are free from contamination as a test, and that the CAT erred in law in attaching greater weight to this latter category of evidence. For reasons set out below legal certainty is a well-established principle of law which has been applied to determine the value of different categories of evidence: see paragraphs [142]-[145] below which explain that, because of the principle, evidence that is available to a dominant undertaking when it sets prices (such as its own costs) is more informative of whether there is abuse, than evidence which the undertaking could not have been aware of at the relevant time.

The nature of merits appeals before the CAT

27. The hearing before the CAT was an appeal on the merits of the CMA Decision. It was not a judicial review. The CAT admitted and took account of new evidence not before the CMA. It endorsed fully the findings of fact and reasoning in the Decision but also made some limited independent findings of fact. The CAT summarised its jurisdiction, by reference to the analysis in Phenytoin:

“121. The fourth main issue on the appeal [in Phenytoin] was as to the extent to which the Tribunal was bound by the CMA’s margin of manoeuvre or discretion in exploring factual matters. Green LJ noted that the CMA had a “margin of manoeuvre” (the terms used by the Court of Justice in Latvian Copyright) or “appreciation” or “discretion” which flowed from the fact that the legal test under Section 18(2)(a) CA 1998 and Article 102(a) is broad brush and necessarily confers a significant latitude upon a competition authority as to the methods and evidence bases that it resorts to in order to prove an abuse of unfair pricing. He continued as follows:

“136. But this is quite different in principle to the question whether the Tribunal, as a supervisory judicial body, must pay deference to that exercise of judgment. Under the CA 1998 the Tribunal has a merits jurisdiction as to both law and fact and upon the basis of established case law it is not bound to defer to the judgment call of a competition authority. It is empowered under the legislation to come to its own conclusions on issues of disputed fact and law and can hear fresh evidence, not placed before the CMA, to enable it to do so.”

122. Green LJ held that the conferral of a merits jurisdiction upon the Tribunal flows from important legal considerations relating to the rights of defence and access to a court, under fundamental rights such as Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights, competition law being treated as a species of criminal law as a recognised in numerous cases. Green LJ summarised the case law as follows.

“140. From case law it is possible to draw various conclusions about the role of judicial bodies in relation to the margin of appreciation of a competition authority: (i) for a (non-judicial) administrative body lawfully to be able to impose quasi-criminal sanctions there must be a right of challenge; (ii) that right must offer guarantees of a type required by Article 6; (iii) the subsequent review must be by a judicial body with “full jurisdiction”; (iv) the judicial body must have the power to quash the decision “in all respects on questions of fact and law”; (v) the judicial body must have the power to substitute its own appraisal for that of the decision maker; (vi) the judicial body must conduct its evaluation of the legality of the decision “on the basis of the evidence adduced” by the appellant; and (vii), the existence of a margin of discretion accorded to a competition authority does not dispense with the requirement for an “in depth review of the law and of the facts” by the supervising judicial body.”

123. Green LJ went on to note that the conferral of a merits jurisdiction did not mean that the jurisdiction of the Tribunal is unfettered. The Tribunal should interfere only if it concludes that the decision is wrong in a material respect. Whether an error is material will be a matter of judgment for the Tribunal. The Court of Appeal dismissed the CMA’s appeal against the Tribunal’s finding that the CMA had conducted an insufficient examination of evidence of comparators and its appeal against the Tribunal’s conclusion that the CMA had failed to take proper account of patient benefit in its assessment of “economic value” as that phrase is used in paragraph [250] of United Brands. It was open to the Tribunal to reach a different conclusion to the CMA on these matters.”

The jurisdiction of the Court of Appeal

28. For an appeal to be mounted either the permission of the CAT or that of the Court of Appeal is required. The test in CPR rule 52.6(1) applies. Accordingly, permission may be granted where either the CAT or the Court of Appeal considers that the appeal would have a real prospect of success or there is some other compelling reason for the appeal to be heard. The substantive jurisdiction of the Court of Appeal is governed by section 49(1) CA 1998 which limits substantive appeals to points of law but imposes no equivalent limitation in appeals concerning penalties:

“An appeal lies to the appropriate court—

(a) from a decision of the Tribunal as to the amount of a penalty under section 36;

(b) …

(c) on a point of law arising from any other decision of the Tribunal on an appeal under section 46 or 47.”

E. Liothyronine pricing

29. The nub of the applications concerns issues relating to principles of pricing. The position is complex. It is necessary, by way of introduction, to explain the issues and to provide a summary of the position as it stands for the purposes of the case before the Court.

30. The target of a merits appeal is the CMA Decision. In this case, after what was in effect a trial, the CAT upheld the Decision on dominance and abuse in all respects. The Decision is therefore the starting point. It is a lengthy document. The substantive content runs to 433 pages and is accompanied by annexes exceeding 200 pages which include the detailed workings of the CMA in relation to the computation of Cost Plus. The CAT summarised the Decision in Section C of the Judgment (paragraphs [80ff]).

31. Three measures or benchmarks of price are important to the CMA Decision and the CAT Judgment:

(i) The first is Cost Plus where the average across the Infringement Period was found to be £4.94. This finding made in the Decision was endorsed by the CAT.

(ii) The second is £20.48 which was the ASP prevailing in the market as of the commencement of the Infringement Period in January 2009. This was a finding by the CMA and was unchallenged before the CAT.

(iii) The third is £21 which is the price the CAT found was a viable entry inducing price or EIP. There was no equivalent finding to this effect in the CMA Decision. It is a finding the applicants challenge before this Court.

Cost plus (£4.94) / comparison with the ASP

32. The CAT having received full evidence and formed its own independent conclusions (Judgment paragraph [149]), agreed with the analysis of the CMA on Cost Plus: Judgment paragraphs [142]-[230] and [347]-[350]. It specifically upheld (cf paragraphs [230] and [348]) the conclusion of the CMA that the prices charged by Advanz during the Infringement Period above Cost Plus were excessive and abusive. There is no challenge to the calculation by the CAT of the applicable Cost Plus. I summarise the position briefly by reference to the reasoning and findings in the Decision.

33. The Decision sets out conclusions on Cost Plus in Section 5 (paragraphs [5.102] - [5.202]), and additional workings are set out in Annex 3 (“Costs plus a reasonable rate of return”) and Annex 4 (“Cost of capital”).

34. In relation to the cost element of Cost Plus the CMA first considered the cost of production. The CMA split the total costs involved in supply into direct and indirect costs and a reasonable rate of return. Without descending into detail, the CMA attributed values to: direct costs per unit; indirect and common costs per unit; amortisation charges; depreciation charges; return on intangibles; return on tangibles; and, return on working capital (see Decision page [197] Table 5.1).

35. In relation to the plus element of Cost Plus this is dealt with in the Decision at paragraphs [5.126ff] under the heading “Reasonable rate of return”. The CMA explained that it was normally necessary to allocate a reasonable rate of return to cover the cost of capital. The reasonable rate of return reflected the opportunity cost to investors of providing capital to Advanz to purchase assets and fund working capital requirements. The CMA applied a return on capital employed (“ROCE”) model.

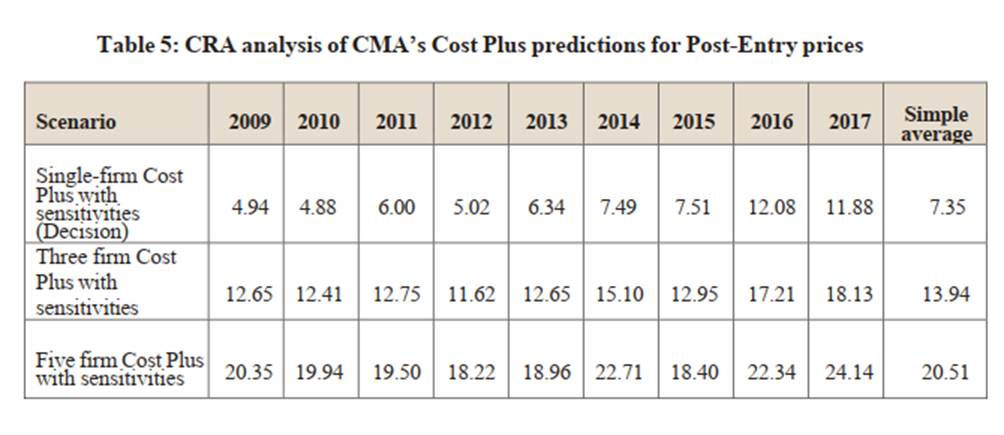

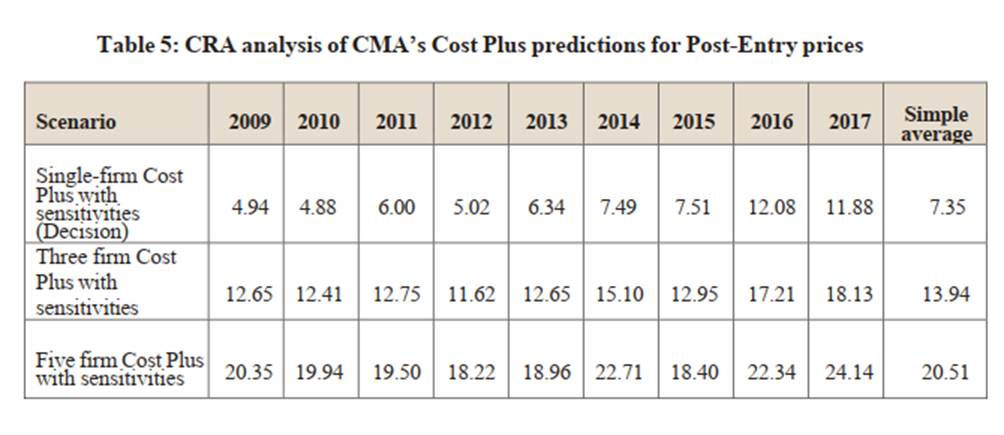

36. The CMA also applied a series of “sensitivities” to Cost Plus relating to: common cost allocation; the approach to product rights valuation; and a reasonable return on capital bracket (i.e. WACC) which were calculated to be “very favourable to the parties”: (Decision paragraph [5.176]). In Table 5.2 (Decision page [201]) it set out its base line average figure for Cost Plus (£4.94) and an adjusted figure to take account of these favourable sensitivities (which led to a simple average of £7.35).

37. The CMA’s conclusion on Cost Plus was cross-checked against a significant number of comparables which the CAT analysed and heard evidence about. It held that: “No adequate explanation was given by the Appellants for Liothyronine Tablets’ outlying status in these comparisons”: Judgment paragraph [277].

38. The CMA addressed, and rejected, alternative measures of a fair price advanced by the parties which posited a much higher price level at which to set the fairness bar: See Decision paragraphs [5.195ff]. These included: post-entry prices; the price of other products similar to Advanz’s Liothyronine Tablets; portfolio pricing; forecast prices; the implications of Cournot modelling; entry plan pricing; and multi-firm pricing.

39. The CMA also considered whether there were other factors which justified taking a higher price as the threshold for fairness. It considered and rejected: the existence of demand side factors which added to the economic value of the product; whether the characteristics of the product could be expected to create enhanced value for consumers; the therapeutic value of the product to consumers; whether customers were willing to pay a premium for the product; whether the prices paid reflected substantial market power; and whether the prices charged were the outcome of agreement between Advanz and the NHS.

40. The CMA’s case was that Liothyronine prices in a competitive generics market should be close to, but typically slightly above, production costs. They would be at or proximate to Cost Plus: see Decision paragraphs [5.285(a)(iii)] and [5.292]-[5.301]. The CAT endorsed this conclusion: e.g. Judgment paragraph [348].

41. In paragraph [5.177] and Table 5.3 the CMA set out conclusions on the differential between the ASP and both the base line Cost Plus and Cost Plus adjusted for sensitivities in the Infringement Period 2009 - 2017. In Figure 5.8 (Decision page [202]) it produced the same information in graphic form showing how Advanz’s ASP had risen relative to Cost Plus (with/without sensitivities) over the Infringement Period. This showed that even the more undertaking-friendly Cost Plus with sensitivities made no real difference to the analysis.

42. Prices charged for Liothyronine were substantially higher than Cost Plus. In 2009 (the first year of the Infringement Period), the differential was 900% per pack increasing to over 6000% at other points relative to September 2007. Figure 1.1 in the Decision tracks the ASP from January 2007 (before the Infringement Period) to July 2017. Paragraphs [1.09] and [1.10] stated:

“1.9 In October 2007, Advanz began applying this strategy to Liothyronine Tablets. At that time, the price of Liothyronine Tablets was £4.05 per 28 tablets and Liothyronine Tablets were already one of Advanz’s top ten most profitable products.

1.10 Advanz removed the ‘Tertroxin’ brand, re-launched Liothyronine Tablets as a generic product, and immediately implemented a price increase. As a result, Advanz nearly doubled the price of the drug overnight. Within a year of de-branding, Advanz had more than doubled its price again and by January 2009, its average sales price (‘ASP’) for Liothyronine Tablets had reached £20.48. Under HgCapital’s ownership (December 2009 to August 2012), the ASP of Liothyronine Tablets increased from nearly £21 per pack to nearly £46 per pack; under the Cinven Entities’ ownership (August 2012 to October 2015), this increased again to nearly £190 per pack. By July 2017, nearly 10 years after de-branding, Advanz had increased the ASP of Liothyronine Tablets from £4.05 to £247.87, representing a price increase of 6,021% since September 2007.”

The price prevailing at the commencement of the Infringement Period (£20.48)

43. I turn now to the figure of £20.48. For reasons of administrative priority, and in accordance with its published policy, the CMA did not formally set average Cost Plus (£4.94) as the ceiling price above which, as a matter of enforcement policy, the Decision was to be predicated. Further, it did not use 2007 as the starting point for the Infringement Period. Instead, it adopted the more conservative (and hence pro-undertaking) figure of £20.48. This was the price at which Advanz was selling the tablets in January 2009 which then marked the commencement of the Infringement Period: see Decision paragraph [1.10] cited above.

44. In relation to the CMA’s conclusion that prices above £20.48 were excessive, and not objectively justified, the CMA set out detailed reasons. The analysis is found in the Decision between paragraphs [5.252]-[5.276] and a summary is set out in paragraph [5.251]:

“5.251 In coming to this conclusion, the CMA has had regard to the following factors:

(a) The substantial disparity between Advanz’s prices and the economic value of its Liothyronine Tablets;

(b) The competitive conditions prevailing during the Infringement Period, including the absence of alternative Liothyronine Tablet suppliers, lack of regulatory constraint, high demand inelasticity, high barriers to entry and lack of countervailing buyer power, enabled Advanz to sustain prices which bore no relationship to economic value;

(c) The commercial purpose of Advanz’s pricing strategy, which was to exploit the lack of competitive pressure on its pricing resulting from the competitive conditions set out at (b) above;

(d) The increases in price were significant, amounting to a 6,021% increase in Advanz’s prices (from £4.05 to £247.87) between the decision to de-brand and Advanz’s highest price; and a 1,110% increase over the Infringement Period (from £20.48 to £247.87), with no material increase in production costs or innovation;

(e) Advanz’s price increases have had a significant adverse impact on the NHS and patients; and

(f) There is no independent or objective justification for the conduct.”

45. The CMA left open the question whether a pre-2009 price above Cost Plus but below £20.48 was excessive and unfair as a matter of law. Paragraph [5.105] of the Decision explained:

“Taking account of its prioritisation principles, the CMA decided to focus its Investigation only on prices of £20.48 per pack (the price in January 2009) and above. The CMA has not reached a conclusion on the exact level (above Cost Plus but below £20.48 per pack) at which Advanz’s prices became excessive and unfair as a matter of law. Therefore, although it is possible that prices somewhere above Cost Plus but below £20.48 per pack may have also been excessive and unfair, the CMA has limited itself to finding that Advanz’s prices were excessive and unfair when they reached at least £20.48 per pack. This means that the lowest price which is covered by the CMA’s infringement finding exceeds Cost Plus by 900% for the year 2009.”

In footnote [2] the CMA reiterated: “The CMA has decided for reasons of administrative priority not to pursue its investigation in respect of Advanz’s conduct during the period from 1 November 2007 to 31 December 2008 or following 31 July 2017. See Prioritisation principles for the CMA (CMA16), dated April 2014.” In footnote [1684] the CMA confirmed that £20.48 was the price charged in January 2009 and stated that prices below that level may also have been excessive and unfair. It added a caveat in footnote [828] where it made the important point that: “Cost Plus already includes a reasonable rate of return. However, as set out in paragraphs 5.65 ff above, not every price above Cost Plus would have been excessive and unfair.” For example, in paragraph [5.87] the CMA, in relation to the concept of “value”, observed in general terms: “The economic value of a product may exceed Cost Plus as a result of non-cost related factors including, where applicable, ‘additional benefits not reflected in the costs of supply’ or any ‘particular enhanced value from the customer's perspective’”.

46. The CMA, for the same administrative reasons, fixed the end of the Infringement Period as 31 July 2017 which was shortly prior to the new market entry of Morningside and Teva. It therefore left open whether Advanz was dominant after the end of the Infringement Period and, if so, for how long. The CMA explained that its calculation of penalties was conservative because it ignored the possibility that prices were excessive and unlawful both before and after the Infringement Period:

“7.134 To calculate the minimum direct financial benefit for each ownership period, the CMA has calculated the difference between its ‘enforcement price’ of (£20.48), that is the lowest price charged for Liothyronine Tablets during the Infringement Period that has been found to be excessive and unfair and Advanz’s actual selling prices during each of the different ownership periods of the Infringement. The resulting figures are then multiplied by the volumes sold in each ownership period. This results in a conservative estimate since profits based on prices that were lower than £20.48 could also be unlawful; the calculation also does not take into account any potential excess profits based on prices charged following the end of the Infringement Period.”

47. Before the CAT the applicants did not, for obvious reasons, challenge the limitation upon the scope of the Decision introduced for administrative reasons. But they did attack the CMA finding of £4.94 as a fair and lawful price and the endorsement of that conclusion by the CAT which was clear that a price above Cost Plus was excessive and unfair.

A viable entry inducing price (£21)

48. The third price of importance is £21. In evidence before the CAT the expert for the CMA, Professor Valletti, opined that Uni-Pharma (a company with experience of selling in the Greek market) made a serious attempt at market entry in 2010 (Judgment paragraph [300]). The evidence on Uni-Pharma was set out in the Decision and was limited to the reason why Uni-Pharma decided ultimately not to pursue its Marketing Authorisation (“MA”) application. The CMA considered generally MA applications made by a variety of third parties and in particular companies that had applied where the application process was ongoing at the time of the Decision (and who had not therefore then entered the market) or who had withdrawn their applications rather than engage in further investment to obtain the MA: see Decision paragraphs [3.99ff]. More specifically, the CMA considered the position of Uni-Pharma which had initiated the application process, but which had then withdrawn citing the costs of carrying out certain studies required by the HMRA as the cause: see e.g. Decision paragraphs [3.110], [4.139] and [4.142].

49. There was a dispute before the CAT on the evidence as to whether the then prevailing price was in fact considered by Uni-Pharma to be a viable entry price (Judgment paragraphs [300] - [301]). In paragraph [308], the CAT recorded the CMA argument that if (which it did not accept) entry inducing prices (EIP) were relevant then the attempt of Uni-Pharma:

“…to enter the UK and Irish markets, which began in 2010, was a credible entry attempt. The CMA accepted that it is not possible to determine whether Uni-Pharma withdrew only because its API manufacturer had withdrawn. It was, however, clear that an experienced manufacturer of hypothyroidism medicines took significant steps towards entry, including through the preparation of a dossier based on an API by a manufacturer in the market and spending €350,000. That was a credible, even if unsuccessful attempt at entry. In the circumstances, the price of £21 at which Uni-Pharma’s entry was sparked (March 2010) would be the relevant benchmark for an Entry Incentivising Price”.

50. The CAT (Judgment paragraphs [317ff]) concluded that the CMA was justified in rejecting EIP as a valid competitive benchmark. It was common ground between the experts that EIP did not reflect the outcome of an effectively competitive market. However, the CAT then made an independent finding of fact which was that, on the alternative hypothesis that EIP were relevant, Uni-Pharma did consider £21 to be a viable entry price:

“325. Had we considered that Entry-Incentivising Prices were a useful benchmark, we would have taken the relevant Entry-Incentivising Price to be the £21 current in 2010 when Uni-Pharma commenced its entry attempt. Although it is not clear to what extent Uni-Pharma’s discontinuance was attributable to the discontinuance of the API or to the need to invest in the bioequivalence study, that price appears to have been considered by Uni-Pharma to be a viable price which merited significant work and costs.”

(emphasis added)

The position before the Court of Appeal

51. Cinven, Hg and Advanz Pharma Corp appealed the Decision to the CAT. They adduced evidence to show that the prices charged were fair when set against various comparators and other benchmarks. This included new evidence which post-dated the Infringement Period and the Decision and covered the period between the Decision and the appeal. The CAT dismissed the appeals. The CAT did however reduce the penalty on a particular ground relating to the need for specific deterrence and reduced the penalty on each appellant accordingly.

52. Cinven and Advanz now seek permission to appeal against the Judgment. They argue that the CAT erred in rejecting their pricing evidence and thereby wrongly found that the abuse was (ignoring administrative enforcement priorities which led to £20.48 being the ceiling for abuse) to be determined by reference to the Cost Plus test. The CMA seeks permission in relation to the reduction in the penalty imposed on Cinven. It does not appeal the equivalent reductions in relation to Advanz or Hg. As to Advanz any appeal would be academic because the penalty, even as reduced, would still be above and therefore subject to the statutory maximum. As to Hg it initially sought permission to appeal but it compromised its dispute with the CMA and this included any appeal by the CMA against the reduction in penalty to Hg.

53. The position before this Court can be summarised as follows. The CAT upheld various factual markers found by the CMA:

(i) Advanz was the sole supplier of Liothyronine Tablets during the period 1st November 2007 to 31st July 2017: Decision paragraph [1.2]. It held a dominant position in the market for Liothyronine Tablets: Judgment paragraphs [142(4)] and also [351]-[391] in relation to the absence of any countervailing bargaining power on the part of the NHS.

(ii) Advanz abused its dominant position by charging excessive prices in excess of Cost Plus which were unfair and abusive from 1st January 2009 to 1st July 2017 (the Infringement Period): Decision paragraph [1.4] and Judgment paragraphs [230] and [347]-[350].

(iii) The average Cost Plus across the Infringement Period was £4.94: Judgment paragraph [145].

(iv) Advanz first applied a price optimisation strategy in October 2007 (Decision paragraph [1.9]) at which point in time the price of Liothyronine Tablets was £4.05 per box of 28 tablets: Decision paragraph [1.9] and Figure 1.1 which show that the price had been c.£4 since at least the start of 2007. The strategy was designed to raise prices to their highest possible level whilst avoiding regulatory scrutiny: Judgment paragraphs [29]-[72].

(v) Between January 2009 and July 2017, the price was increased upon 63 occasions: Judgment paragraph [32].

(vi) The first point in time when prices went above average Cost Plus was October 2007 (when it rose to £8.05): Decision paragraph [3.190(b)] and Figure 3.2 .

(vii) As of July 2017, the price was c.£247 per box: Decision Table 1.1 page 10.

(viii) There were no objective, technical, safety or other considerations which justified the price increases: Judgment paragraphs [216], [321]. In a competitive market competition would (once initial fixed costs had been recovered) “drive prices closer to the direct costs of production”: Judgment paragraph [228(3)].

(ix) New entry to the market occurred in August 2017 (Morningside) and September 2017 (Teva) when the ASP was c.£247: Judgment paragraph [74]-[79].

(x) Without prejudice to whether Advanz still held dominance, market wide prices following the Infringement Period, causally, remained contaminated by the prior abuse: Judgment paragraphs [268] - [281].

(xi) Uni-Pharma considered £21 to be a viable entry price: Judgment paragraph [325].

54. In addition, the CAT did not: (i) disturb the decision of the CMA to choose a date of January 2009, and the then prevailing price of £20.48, as the start of the Infringement Period for administrative reasons; or (ii), disagree with the CMA that Advanz might have been dominant and acted abusively after the Infringement Period.

F. Key facts as found by the CAT

55. The facts are set out fully in the Judgment. I set out below a summary of the matters of greatest relevance to the applications before this Court. Those concern: (i) The pricing regime; (ii) the strategy of Advanz behind the pricing of Liothyronine tablets to the NHS; and (iii), post-Infringement Period entry into the market.

The pricing regime

56. Branded drugs are subject to price regulation pursuant to a voluntary scheme agreed between the DHSC and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. During the Infringement Period this regulation occurred via a voluntary arrangement known as the pharmaceutical pricing regulation scheme ("PPRS") which applied to manufacturers and suppliers of branded medicines to the NHS. Advanz was a member of the scheme. However, since Liothyronine Tablets were unbranded after 2007, the PPRS did not apply during the Infringement Period.

57. The cost of prescriptions for generic drugs is funded via a reimbursement price paid to dispensing pharmacies for completing NHS prescriptions. The reimbursement price is set out in a list known as the Drugs Tariff (“DT”) published upon a monthly basis by NHS Prescription Services on behalf of the DHSC. Drugs covered by the Drug Tariff are allocated to one of three categories: A, C or M. These determine the price for the product. Category M applies to commonly used generic drugs available from several sources. Category A drugs must be listed either by two wholesalers or by one wholesaler and by two manufacturers. Between December 2007 and November 2010 Liothyronine Tablets were not included in the Drug Tariff and the price paid to Advanz by the NHS was the list price. From November 2010 to April 2015 the tablets were listed in category A of the Drug Tariff. In May 2015 they were moved to category C where they remained until March 2018 when they returned to Category A. In January 2019 the tablets were moved to Category M.

58. During the Infringement Period Scheme M was a voluntary scheme concluded between the Secretary of State for Health and the BGMA. During the Infringement Period the pricing of Liothyronine Tablets was subject to Scheme M. It applied to manufacturers and suppliers of generic drugs sold to the NHS and it permitted members to alter the price at which medicine was sold to wholesalers or dispensing contractors without any requirement to discuss such changes with the NHS in advance. Members notified price changes to the NHS and they would be paid. The provisions of Scheme M specified that the DHSC could intervene to ensure that the NHS paid a reasonable price for the drug if it appeared that normal competitive conditions were not operating so as to protect the NHS from significant increases in expenditure.

The strategy of Advanz behind the pricing of Liothyronine tablets to the NHS

59. In 2007 Advanz de-branded the product and thereafter sold it as a generic. It amended the MA to remove the branding and gave the drug its generic name as set out in British Pharmacopoeia (“Liothyronine”). The decision to de-brand was part of a strategy by Advanz to increase profitability through price increases. The Decision records how this strategy evolved over time as evidenced in internal documents. There is no challenge to inferences drawn from this material. It is said though that whilst it might well convey a pejorative feel or tone, this has no bearing upon any issue relevant to the allegation of abuse. I agree that it is necessary to be careful not to be swayed by the tone of the exchanges. Businessmen sometimes use flamboyant and provocative language (“let’s kill the competition”) which can be ambiguous and open to a number of meanings. Nonetheless, that does not mean that documents relating to strategy lack relevance where they provide evidence and information such as how competition in the market operates, the supplier’s strategy, and provide a benchmark against which claims that the pricing strategy was objectively justified can be measured. The CMA and CAT were correct to treat internal documents which evidenced intent as capable of having probative value. See further paragraph [123] below.

60. By de-branding, products were removed from the PPRS and from price regulation. The CAT (Judgment paragraphs [31] and [32]) summarised the policy as it stood in 2007:

“31. The decision to de-brand was part of a strategy by Advanz to drive an increase in profitability through price increases. By de-branding, products were removed from the PPRS scheme and hence from price regulation, as recognised in Advanz’s UK business plan for branded pharmaceuticals in April 2007:

‘The way in which the PPRS scheme works means that price increases cannot be made easily on branded products. In order to drive price increases there is a strategy to move to the generic name and increase prices.

…

A range of products can be moved from branded to generic resulting in their removal from the current PPRS scheme and hence from price regulation. Prices on these products can be increased.’

32. John Beighton, Advanz’s former CEO, speculated in his witness statement about other possible reasons for the decision to de-brand (a decision which was taken several years before he joined Advanz), including the obsolescence of the Tertroxin brand name but these are not reflected in the contemporaneous documents. Advanz proceeded to implement a series of price increases in accordance with this strategy. Immediately prior to the de-branding of Tertroxin in October 2007, the average selling price (“ASP”) for the drug was the equivalent of £4.05 per 28 tablet pack. It was Advanz’s seventh most profitable product in its portfolio of 62 drugs. Having de-branded the drug, Advanz reduced the pack size from 100 to 28 and immediately increased its ASP to £8.05 per pack, in effect nearly doubling the price. A series of 63 individual price increases followed …”

61. The CAT cited from a due diligence report prepared by McKinsey and Company prepared for Hg which acquired the business in 2009 as part of a management buy-out and which highlighted the inadequacy of competitive pressures as an explanation for the “extraordinary” success of the strategy of exploiting niche generic drugs:

“33. The reason behind the extraordinary success of the pharmaceutical division in the difficult generics market in the UK is the efficacious management of its product portfolio within the regulation schemes in the UK: Trojan (i) manages to position its products in niches where competition is absent or very limited, (ii) optimally manages their products within the regulatory pricing schemes (branded and non-branded). Often their sales level stays under the radar screen of potential new entrants, thus protecting their business.”

62. Additional disclosed material (e.g. reports and presentations) from the time of the subsequent sale to Cinven in 2012 addressed: whether significant price increases would have a negative effect on volumes; the absence of competitors; the high barriers to new entrants; and the favourable regulatory environment. A report in May 2012 from IMS Consulting Group entitled “Project Glacier Final Report” suggested that a price of £60 per pack was sustainable. This highlighted that there was an off the radar “niche” in the market which sat between the commercial ranges of small generic companies and large players in which the applicants would be uniquely well positioned. The report referred to: “…niche products that fall under the radar of large players but above the size threshold of small generic companies. Furthermore, these products are difficult to manufacture thereby reducing the risk of new competitors.” Other internal documents refer to this niche as not being economically viable for new entrants to invest resources in to develop competing products.

63. This niche was also immunised from the risk of regulatory intervention. Documents refer to the: “… particularly beneficial reimbursement mechanism which, whilst effective for high volume products which is what the NHS cares about does allow for niche players to achieve good margins”. An Investment Recommendation submitted to the Cinven Investment Committee on 2nd July 2012 included the following:

“Reimbursement for drug manufacturers is controlled by a small group within the DoH, who aim to minimise the NHS’ £11bn drug bill whilst ensuring drug availability The focus is on high volume drugs (patent and off-patent) as this is where the absolute quantum of savings is higher: niche products are typically below the radar […]

Some of Mercury's products display price inelasticity, with no volume response from successive price increases.”

And later:

“Mercury therefore operates below the radar and capitalises on opportunities to achieve volume and pricing growth even in such a heavily regulated market.”

64. An illustration of the way in which price inelasticity and the absence of regulatory oversight for therapeutically important drugs played out was described in an internal email dated 19th July 2012. This indicated that the price optimisation strategy applied to Liothyronine was applied to other drugs as well:

“All these products are life saving products and exclusively marketed by Mercury Pharma only. There is no other substitute in UK market for these products. After de-branding ... we have increased the prices continuously in last 3 to 4 years. We have also changed the pack sizes of the products without reducing the prices. Few of the examples are like ... Liothyronine, where we have reduced the pack size from 100 to 28 ... we could continue increasing the prices [year on year] subject no other company introduces these molecules. Since these are de-branded therefore they do not have any PPRS liability also.”

65. The Decision (paragraph [5.257]) records that a Cinven Partner observed in July 2012, shortly before Cinven’s acquisition of the Advanz business from Hg, that what drove generic prices upwards was oligopolistic market structures, not demand growth:

“… the business’s ‘primary “tail wind” is price increases passed on the payor because of the oligopolistic nature of most segments it operates in, rather than a real growth in volume for each drug’ and the business model relied upon the ‘European healthcare systems … under very strong pressures [not reacting because] “it is too below the radar screen/noise”.”

66. The Judgment (paragraphs [46]-[53]) cites a slide pack presentation given by Mr Beighton to lenders (September 2012), shortly after Cinven’s acquisition of the business. This shows that for off-patent products there was no research spend, strong barriers to entry and pricing power. The CAT cites from accompanying speaking notes. Examples include:

“Attractive position - niche off-patent products insulated from key pharma risks -

No R&D spend or patent cliff -

Little/no competition - pricing/margin power -

Strong entry barriers mean position sustainable.”

Another slide entitled “Differentiated product portfolio benefits from high barriers to entry” highlighted barriers to entry:

“Manufacturing Process

• Products require complex manufacturing process and have difficult to determine formulations

Regulatory Approval

• Competitors entering market need to obtain new marketing authorisations

• Process is costly and can be time-consuming (c.3-4 years)”

67. The existence of high entry barriers does not preclude the possibility that ultimately they are surmountable. If the prevailing price is very high, there might come a time when potential competitors are incentivised to incur the burdens and costs of overcoming the barrier in order to exploit the high price on the other side. The CAT found (Judgment paragraph [61]) that there was appreciation from May 2013 onwards on the part of Advanz that if prices continually went upwards, entry was to be expected. It was foreseen that this pricing strategy could provoke entry relatively soon. The plan was to maintain price increases including before the anticipated generic entry. Advanz should, opportunistically, “take what it can now”. The CAT observed:

“A presentation document headed “UK key molecules” forecast loss of volumes in 2017 offset by increased prices, achieving year on year revenue gains in the period 2015 to 2018. This was consistent with the strategy adverted to in an email dated 31 May 2013, some two years earlier, in which Mr Beighton advocated a price increase in relation to another drug (Prednisolone):

“… because I am pretty sure that we are going to get competition within the next year or so. I know of at least [one other supplier] that are developing. Therefore we should take what we can from it now. I think Liothyronine may be a similar story…”

68. Other documents refer to there being no need for innovation because the drug had long established “strong efficacy and safety” (Judgment paragraph [64]).

69. By 2016 there was press commentary focusing upon the increase in tablet prices and predicting an adverse NHS response. The CAT observed that this had no impact upon sales:

“67. The price increases also attracted adverse scrutiny in the press. An article in the Times dated 5 June 2016 reported that doctors had been encouraged to stop prescribing Liothyronine after the price of a tablet shot up from 16p to £9.22. The article was forwarded within Advanz, prompting concern that the change of guidance might impact on sales. In response to an internal enquiry as to what was meant by the reference in the article to the NHS encouraging doctors to stop prescribing Liothyronine, and whether there would be a big impact, the answer was as follows:

“Business as usual. We have seen a very small volume decline over the last 18 mths but it is very small (1-2%). So we characterise the market and volumes as flat!”

68. A subsequent internal email dated 29 June 2016 commented as follows: “[…] In short -- nothing new. The most important thing about this is the date. [The] ... DROP-List is published every year. It was published a year ago and our volumes remain flat. Thus, it has had no impact on the sales volumes.”

70. Ultimately, the continued upward trajectory of prices did trigger regulatory intervention (Judgment paragraphs [71] and [72]). In 2017 an NHS Clinical Commissioners consultation occurred which led to guidance being issued to CCGs to reduce the prescribing of Liothyronine Tablets on cost grounds. As a result, some patients previously prescribed with Liothyronine Tablets had their treatment withdrawn. Some were able to obtain supplies privately. Following the publication of an adverse Times article (June 2016), Jeremy Hunt, the then Secretary of State for Health, asked the CMA to look into whether drugs companies had been guilty of excessive pricing.

Post Infringement Period entry into the market

71. Advanz was the only holder of an MA for Liothyronine Tablets throughout the Infringement Period which ran to the end of June 2017, at which point in time the ASP was at about £247 per box. Subsequently, a number of MAs for Liothyronine Tablets have been granted. The first was to Morningside in June 2017. It commenced development in 2012 and submitted its application for an MA in July 2015. This resulted in a number of deficiency letters from the MHRA. Morningside considered that “the process for obtaining [an MA] was … challenging”, despite receiving “tremendous support from the MHRA.” Morningside ultimately commenced supplying Liothyronine Tablets on 21 August 2017. On 14 August 2017, the MHRA granted an MA to Teva. It first contacted the MHRA regarding an MA application in November 2014 and submitted an application in December 2016. It began supplying Liothyronine Tablets at the end of September 2017. Accord-UK, initiated a development project for Liothyronine Tablets in 2012 and submitted an MA application in June 2020. Sigmapharm submitted an application in 2019. Both now have an MA.

G. Issue I - “Workable competition”: The minimum conditions necessary for a workably competitive market/Workability as a bright line test of fairness

The issue

72. I turn now to Issue I. In Phenytoin the Court (paragraph [97(i)]) held that “…in broad terms”, a price was unfair and an abuse when the dominant undertaking reaped trading benefits which it could not have obtained in conditions of ‘…normal and sufficiently effective competition’, i.e. ‘workable’ competition”. The applicants argue that the acid test is therefore whether the disputed prices are generated in a market characterised by a structure reflecting workable competition. If they are then they must be lawful even if they are way above Cost Plus. The applicants argue that the Cost Plus approach adopted by the CAT was wrongly based upon the persistence of market power, a failure to determine fairness by reference to pricing which would stimulate competition, and was divorced from any test of workable competition.

73. To support the centrality of market structure to the analysis the applicants refer to National Grid v Gas and Electricity Markets Authority [2010] EWCA Civ 114 at paragraph [85] where this Court noted that “competition rules promote consumer welfare indirectly by their effect on market structure and the promotion of competition”. Further, Case C-95/04 P, British Airways v. EU Commission ECLI:EU:C:2007:166 is cited where Advocate General Kokott stated:

“68. The starting-point here must be the protective purpose of Article [102]. The provision forms part of a system designed to protect competition within the internal market from distortions […]. Accordingly, Article [102], like the other competition rules of the Treaty, is not designed only or primarily to protect the immediate interests of individual competitors or consumers, but to protect the structure of the market and thus competition as such (as an institution) […] In this way, consumers are also indirectly protected. Because where competition as such is damaged, disadvantages for consumers are also to be feared.”

74. A sharper test for demonstrating workable competition was put forward focusing upon prices generated in a market where three cumulative conditions prevailed: (i) no market dominance; (ii) no collusion; and (iii); no insurmountable barriers to entry. Any price generated in such a market was necessarily lawful. Cinven produced for the Court a graphic which encapsulated its proposition:

Analysis

75. I do not accept the argument. There are four points to make.

The role of workable competition as a test for fairness

76. First, the graphic suggests that any price which falls below the horizontal line representing the threshold for workable competition is automatically lawful and they rely upon this to undermine the reliance by the CAT upon Cost Plus . In this the applicants wrongly elevate broad economic generalisations about workable competition into mandatory hard and fast principles of law. It is important to be clear about the implications of different phrases which are used in the case law. The term “workable competition” is a short hand for the language used in United Brands (ibid) paragraph [249] of “normal and sufficiently effective competition” and this, itself, is a shorthand for fairness, which is the legislative test. The concept of “workable competition” was formulated by John Maurice Clark in the American Economic Review in June 1940 in an article entitled “Towards a concept of workable competition” and was developed as an antidote to the economic concept of “perfect competition” which emerged in the late 19th century literature in which paradigm markets were described as in optimal equilibrium where output was equal to marginal cost. It was early understood, however, that the use of perfect competition as a tool for understanding how markets really operated, or for determining regulatory policy, was unrealistic and attention turned to workable competition as a practical alternative. This spawned an enormous body of literature over the decades. For example, Jesse Markham in June 1950, in a classic article entitled “An Alternative Approach to the Concept of Workable Competition” , highlighted both the utility of the concept but also its shortcomings including its lack of “precise definition”. Even today there is no consensus as to the exact parameters of the workably competitive market.

77. This judgment is not the place to embark upon an analysis of the literature. I observe only that there is agreement that competition law regulation does not proceed upon some theoretical, laboratory, model of perfect competition but upon the real world and focuses upon achieving the acceptable or adequate as opposed to the paradigmatic. Evidence of how a market reflecting “normal and sufficiently effective competition” or “workable competition” operates might therefore be relevant, and even important, evidence in a case but it is not a mandatory test. There is no rule that a regulator or Court must seek out evidence of what might happen in an actual market said to exhibit the features of workable competition as a benchmark. The premise which underlies the applicant’s graphic depiction of a bright line test is thus unsupported in the jurisprudence. The case law, as summarised in Phenytoin at paragraph [97] (see paragraph [24] above), describes practical approaches to determining fairness as the legislative test. It is understood that, to make the law practicable, there must be evidential proxies for determining what a fair price would be if generated in sufficiently effective, workably competitive, market conditions. It also makes clear that there is a wide range of economic and accounting models, as well as a variety of sources of evidence (e.g. comparables), that can be used to this end. As observed this does not mean that evidence of a broad nature about market structure is irrelevant but it does mean, contrary the applicants submissions, that in an appropriate case Cost Plus, is a valid and sufficient way of establishing whether prices are “fair” and, to this extent, can be said to reflect those that would be generated in a sufficiently effective, workably competitive, market: United Brands paragraphs [248]-[252] and Phenytoin paragraph [97(i)-(v)]. This is notwithstanding that a Cost Plus exercise is performed in relation to a dominant undertaking operating in a market which is not workably competitive.

The cessation of dominance: The persistence of abusive effects (contamination and price stickiness)

78. Secondly, at the most basic level it is correct that a market will not be workably competitive where there is a single monopolist or incumbent dominant undertaking. This is why the law imposes a “special responsibility” upon the dominant undertaking to act fairly. The market cannot bring about that result by itself, so the law plugs the gap. Accordingly, the cessation of that position of market power may be a factor relevant to a conclusion that a market is workably competitive. However, that analysis is incomplete.

79. The CMA and CAT both found, as a fact, that prices, post entry, were “contaminated” i.e. bore the lingering effects of the prior abuse. In other words the prior abuse by Advanz led, causally, to prices across the entire market (whether charged by the applicants or third parties) being higher than they should have been, upon a persistent basis. The continuing contamination was made possible by the uncompetitive nature of the market, even following new entry. In this respect given that entry occurred when the ASP was £247 (which no one has sought to defend economically as non-abusive ) compared to an average Cost Plus of £4.94, which the CMA and CAT found was reflective of prices in a competitive generics market, prices would have to tumble a long way before they reached some workably competitive equilibrium at which point in time it might be said that the effect of the abuse had disappeared from the system. The position of the CMA, which the CAT endorsed, was that a competitive market was in the proximity of Cost Plus.

80. In fact before the CAT there was no real dispute (Judgment paragraph [243]) that, even when dominance was lost, the rate at which prices would adjust from the towering height of £247 to normal competitive conditions would, to use the terminology of the experts and counsel, be “sticky” or “gelatinous”. Mr O’Donoghue KC, for Cinven, accepted that there would be some period of adjustment and that the rate of decline might be retarded (i.e. sticky or gelatinous). This was also the view of all the experts before the CAT. There was disagreement on the evidence as to whether prices had in fact fallen to competitive levels but there was a broad consensus that a period of adjustment would occur and that it would not be immediate.

81. In the Joint Experts Report the experts were asked to comment on the following proposition (at A.22):

“The evolution of prices for Liothyronine Tablets indicates that prices do not adjust immediately to competition. Instead, they show a degree of “stickiness”.”

Professor Valletti for the CMA replied: “Agree. [Valletti ¶68] This point is considered in the Decision at paragraph 5.311. Recent price data submitted by the CMA to the Tribunal confirm the aspect of “stickiness” in this market: prices keep decreasing continuously by about 30% a year and are expected to decrease further.” Dr Bennett for Cinven agreed that prices might yet fall to lower levels, but he thought that competition might still be workable. He replied: “Agree with a qualification: Liothyronine prices have adjusted over time (as opposed to quickly reaching a single price). However, I do not agree that the fact that prices have not reached their minimum level can be viewed as evidence that there is not workable or effective competition. [Bennett 1 ¶79].” Ms Jackson for Hg did not express a view as to whether prices had in fact fallen to their nadir, but she agreed that they do not stabilise at a lower rate immediately upon entry. She replied: “Agree. The CMA uses the term “sticky” to refer to prices that do not stabilise immediately at a new level post-entry, and I agree that this is the case in Liothyronine. However, I disagree with the CMA’s conclusion that this is evidence that competition in Liothyronine is insufficiently effective, and/or that post-entry prices 3.5 years or even nearly 5 years after entry are uninformative competitive benchmarks. [Jackson 4 ¶64-71, Jackson 6 §2]”.

82. The starting position adopted by the experts was plainly correct. References to workable competition in case law are used in a highly relative way. As the CAT correctly observed the test is not the mere existence of some competition. It is whether the competition that actually exists is “normal” or “sufficiently effective”, critical qualifications governing what is “workable”. The emergence of the first green shoots of competition in a market is not therefore an indication that the market is at that point necessarily “normal” or “sufficiently effective” or “workable”. That market might (but will not necessarily) arrive at a mature, workably competitive, state at some point in the future. In this context a test of contamination has to be correct. Otherwise, a sufficiently effective, workably competitive, market would be deemed in law to exist where there was enduring anticompetitive taint by prior abuse. The argument that post-entry the level at which prices settle is decisive evidence of a competitive market but which ignores the possibility that the settled price remains contaminated by the prior abuse, is not credible.

83. It follows that a bright line test which posits the cessation of dominance as a determinative condition, but which ignores the possibility that the post-dominance effects of abuse continue to distort a market, is incomplete and lacks evidential and economic support.

84. As an aside I note that there is no finding in this case by either the CMA or the CAT as to when dominance ceased to exist. It appears to have been accepted that dominance was lost at some point following entry by Morningside and Teva in 2017 but there is no finding as to when this tipping point was reached. This was because the CMA adopted, for administrative prioritisation reasons, the date of 1st July 2017 (immediately prior to first entry) as the cut off point for the formal finding of infringement and the imposition of penalties but has left open the question of breach thereafter: see paragraphs [43]-[47] above. It thus remains possible that Advanz was dominant for some period of time after the end of the Infringement Period.

The absence of collusion: The existence of conscious parallelism

85. Thirdly, the applicant’s test also assumes that absent collusion there can never be anti-competitive market effects which are equivalent to the distorting effects of collusion. This ignores the well-established possibility that markets where there is no dominance and no collusion can still be seriously uncompetitive because of what is sometimes termed “tacit collusion”, “conscious parallelism”, or “oligopoly pricing”.