MR JUSTICE ARNOLD :

Introduction

1.

This is a boundary dispute concerning two properties in Lyme

Regis called “Kaduna”, which is owned by the Claimant (“Ms Pollock”), and

“Rivendell”, which is owned by the Defendants (“the Oldfields”). The location of

the properties is shown in the plan reproduced below.

2.

Ms Pollock exchanged contracts to buy Kaduna on 7 March 2014 and

completed on 22 April 2014. When she took possession of the property, she found

that a 6 metre or so high line of hedging plants (including blackthorn and

hazel) and trees along Kaduna’s western boundary had been cut back to the level

of the earth bank on which it grew. Ms Pollock was unhappy about this, and

brought a claim against the Oldfields for damages and an injunction on the

basis that the bank and hedge were part of Kaduna. The Oldfields accepted that

the work on the hedge had been carried out by Mr Oldfield and another

neighbour. The Defendants denied any wrongdoing on the grounds that (i) the

bank and hedge were part of Rivendell and (ii) in any event the work had been

done before Ms Pollock acquired any interest in Kaduna.

3.

There were three issues at trial. First, where was the boundary between

Kaduna and Rivendell? The boundary area consists of (i) the bank and hedge

which runs between the two properties for a distance of about 30 metres from

the northern end and (ii) a lonicera hedge without a bank which occupies the

final 12.5 metres or so of the boundary at the southern end. Ms Pollock

contended that the boundary was to the west of the bank. The Oldfields

contended that the boundary was to the east of the bank. Secondly, when had the

hedge been cut back? Ms Pollock contended that it was in mid-April 2014, the

Oldfields that it was in late February 2014. Thirdly, if the cutting back of

the hedge was wrongful, what was the appropriate relief? Ms Pollock claimed

damages of about £100,000 and an injunction. The Oldfields contended that she

had suffered no loss and no injunction was required.

4.

So far as the boundary issue was concerned, it was common ground at

trial that:

i)

this issue depended on the proper interpretation of a conveyance dated

16 November 1928 (referred to at trial as “the Operative Conveyance”) by which

a field which is now part of Rivendell (Field 170) was transferred out of

common ownership with a field upon part of which Kaduna now stands (Field 174)

following an auction on 26 September 1928;

ii)

the Operative Conveyance was to be interpreted by reference to what a

reasonable person with the document in his hand and all the admissible

information available, which would include the topographical features of the

land at the date of document, would understand it to mean;

iii)

the relevant boundary was marked by a line on a plan attached to the

Operative Conveyance on which there is a “T-mark” indicating that the boundary

feature was owned by the purchaser of Field 170;

iv)

the bank had been there for a very long time, and hence had been present

at the time of the Operative Conveyance; and

v)

the bank had at all material times stopped short of the southern

boundary leaving a gap.

5.

Ms Pollock’s case was that the line on the plan in the Operative

Conveyance represented a stock-proof fence running along the western side of

the bank. The Oldfields’ case was that the line on the plan represented the centre

line of the bank extrapolated to the southern boundary and that, by virtue of

the T-mark, the legal boundary lay along the eastern edge of the bank. Thus a

key factual issue was whether, at the time of the Operative Conveyance, a

stock-proof fence had been in existence to the west of the bank. A related

question was what, if anything, had occupied the gap between the bank and the

southern boundary. Ms Pollock’s case was that the stock-proof fence had

extended to the southern boundary. The Oldfields’ case was that the gap had

been filled by a hedge.

6.

The action was tried by HHJ Parfitt sitting in the County Court at

Central London between 12 December 2016 and 26 January 2017. He had the benefit

of a site visit. In addition to the site visit, the trial took six days, during

which the judge heard evidence from eight witnesses of fact and four experts.

On 6 April 2017 the judge handed down a careful and detailed reserved judgment

running to 105 paragraphs. He concluded that there was no stock-proof fence to

the west of the bank at the time of the Operative Conveyance, and that the

proper interpretation of the Operative Conveyance was that the line on the plan

denoted the bank. Accordingly, he found in favour of the Oldfields on the

boundary issue and dismissed the claim. On the second issue, he found that the

works were done in April 2014 and thus the works would have constituted an

actionable wrong if the hedge had formed part of Kaduna. On the third issue, he

assessed damages at £22,500, but held that an injunction was unnecessary.

7.

Ms Pollock now appeals against the judge’s conclusion on the boundary

issue with permission granted by Snowden J on three out of six proposed grounds

of appeal. There is no challenge by the Oldfields to the judge’s conclusions on

the second and third issues if Ms Pollock succeeds on the boundary issue.

The Operative Conveyance

8.

By the Operative Conveyance, the land which now

comprises the southern garden of Rivendell was conveyed by a Mr Woodroffe to a

Mr Worth as part of Field 170. The parcels clause of the 1928 Conveyance conveyed:

“ALL THAT piece or parcel of land situate on the Sidmouth

Road in the Parish of Lyme Regis in the County of Dorset containing an area of

Three acres two roods and thirty four perches or thereabouts and more

particularly delineated and described on the plan drawn on these presents,

Numbered 170 and surrounded with the colour pink…”.

9.

The plan is reproduced below.

10.

The plan shows a number of T-marks on the boundaries of Field 170,

including a T-mark on the boundary between Field 170 and Field 174 facing

inwards towards Field 170 showing that that boundary was the responsibility of

the owner of Field 170.

11.

Field 171, which contains a woodland plot now

forming part of Kaduna, was separately conveyed by Mr Woodroffe to Mr Worth on

the same day. The main plot at Kaduna, which formed part of Field 174, was conveyed

to a Mr Lane four days later on 20 November 1928.

The documentary evidence

12.

The principal items of documentary evidence which are relevant to

the issue as to whether there was a stock-proof fence to the west of the bank are

as follows.

13.

The 1841 Tithe map. The 1841 Tithe map, which is reproduced below, shows a “tongue” of

land extending from what became Field 170 (then known as 387) into Field 174

(then known as 385). Thus, whilst the bank was probably in place in 1841, no

boundary feature is shown in the gap to the south. The tithe apportionments

record that Field 170 and Field 174 were both arable fields.

14.

The 1890 OS map. By

the time of the 1890 Ordnance Survey (“OS”) map, which is reproduced below, a

re-organisation of the fields had taken place: the “tongue” of Field 170 had

been absorbed into Field 174 and the map shows a boundary feature which extends

all the way to the southern boundary.

15.

Counsel for Ms Pollock submitted that Field 170

had become a pasture field by this date. I was not shown any evidence which

establishes this; but the point does not matter because it is clear (for the

reason explained in paragraph 18 below) that it was a pasture field by 1928.

16.

Subsequent OS maps in 1903 and 1929 (which was

probably based on a survey in 1928) show that Fields 170 and 174 retained the

same basic configuration up until 1928.

17.

The 1890 and 1909 photographs. Two photographs, taken in 1890 and 1909, of other fields nearby in

Lyme Regis, show stock-proof fences in place. In the case of the 1909

photograph, it shows a fence in front of a hedge. The point of this evidence is

simply to show that stock-proof fences were in use in the area in the relevant

period.

18.

The auction particulars. Fields 170, 171 and 174 comprised

three of seven lots sold at auction on 26 September 1928. The

auction particulars described Lot 4 (Field 170) as “a valuable pasture field”, Lot

3 (Field 171) as “pasture land and shed” and Lot 5 (Field 174) as “a very

valuable arable field”. All three fields were sold subject to a tenancy in

favour of a farmer, a Mr Hallett, but he had served notice to quit at 25

December 1928. Lot 2 was a farm which included “Cowstall with 17 tyings”, also

let to Mr Hallett. Note 8 to the particulars stated:

“BOUNDARIES: Should any dispute arise with regard to the

boundary or boundary fences of any Lot where it adjoins any other Lot, or the

Vendor’s property, the same shall be submitted to the sole arbitration of the

Auctioneers.”

19.

The 1936 Conveyance. By a conveyance dated 3 March 1936 (“the 1936 Conveyance”) Mr

Worth conveyed to a Mrs O’Donnell a triangle of Field 170 as shown by the plan

reproduced below.

20.

The 1936 Conveyance imposed a covenant on Mrs

O’Donnell to “erect a sufficient stock proof fence on the south west boundary

of the property hereby conveyed, and … thereafter maintain the same”. It can be

seen from the plan that the south-west boundary forms the hypotenuse of the

triangle.

21.

The 1935 and 1936 letters. During the conveyancing process, Mr Worth’s solicitors wrote to Mrs

O’Donnell’s solicitors on 17 December 1935 (“the 1935 letter”) saying:

“We duly received your letter of 13th

inst. and have spoken to our client thereon. He would like the matter to stand

over for a time and to meet your client on the spot, as thinks there is some

slight discrepancy in the measurements, probably due to the breadth of the

hedge [bank], but he is sure that they can come to an agreement as to this.”

The copy of the

letter in evidence is in manuscript and the word in brackets is unclear, but it

is probably “bank”. Thus this letter provides some evidence of a hedge on the

bank at that date.

22.

Mr Worth’s solicitors wrote to Mr Worth on 19

February 1936 (“the 1936 letter”) asking about the answers to some requisitions

on title they had received from Mrs O’Donnell’s solicitors, one of which was:

“To whom does the easterly hedge belong – we

assume this is yours, but would like you to confirm.”

The “easterly

hedge” is presumably a reference to a hedge on the bank. What Mr Worth said in

response to this question is unknown.

23.

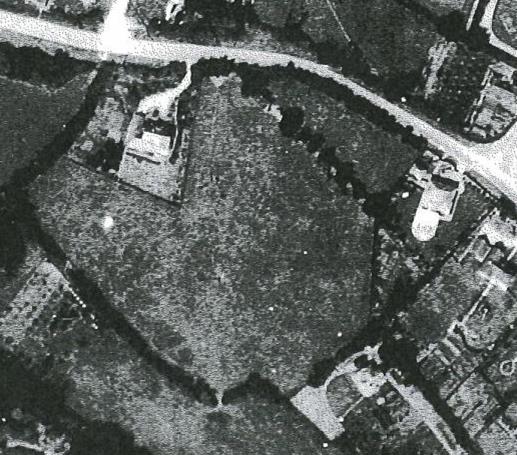

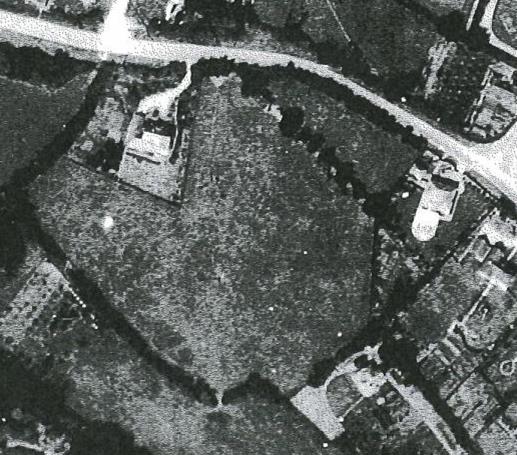

The 1940 photograph. An aerial photograph was taken by the RAF on 18 August 1940, the

relevant part of which is reproduced below.

24.

The photograph shows the house that was

constructed on Field 174 (i.e. Kaduna) during the course of the 1930s. Field

170 appears to remain a pasture field. The triangular plot sold to Mrs

O’Donnell is clearly visible, as is the hedge on the bank. A physical feature is

just about visible in the gap between the bank and the southern boundary next

to what might be a driveway or area of hard standing.

25.

The 1946 photograph. Two

aerial photographs were taken by the RAF on 13 April 1946. Mr Maynard

used these to form a stereo-pair capable of being viewed in three dimensions,

which aids interpretation. While Mr Maynard’s interpretation was based on the

stereo-pair, it is sufficient for present purposes to refer to one of these

photographs, the relevant part of which is reproduced below. It shows a

physical feature extending between the hedge on the bank and the southern

boundary. As Mr Maynard pointed out, the feature in question appears to be aligned

to the western edge of the hedge, and hence the bank.

26.

Later photographs taken in 1951, 1957, 1962,

1995 and 2000 appear to show the hedge on the bank growing ever bigger.

Witness evidence

27.

Field 170 remained a pasture field right up

until 2006 when the Oldfields purchased part of it. Evidence

was provided by a number of farmers who had used Field 170 over the last 20-30

years to keep sheep. They had all maintained a stock-proof fence both in front

of the bank and across the gap to keep their sheep in the field.

The judge’s reasoning

28.

The judge’s reasoning with respect to the boundary issue extends over 43

paragraphs of his judgment ([18]-[60]). He first considered the Operative

Conveyance ([18]-[20], then the non-topographical context (consisting primarily

of the auction particulars) ([21]-[25]), then the topographical context ([26]-[54])

before turning to the interpretation of the Operative Conveyance ([55]-[60]).

He divided his consideration of the topographical context into the following

headings: the bank ([26]-[28]), the area south of the bank ([29]-[43]), the use

of Field 174 in 1928 ([44]) and the presence of a parallel fence in 1928

([45]-[54]).

29.

The judge’s reasoning on the question of whether there was a stock-proof

fence along the line of the bank and filling the gap in 1928 can be summarised

as follows.

30.

First, the judge considered the OS maps and

concluded as follows:

“31. … It is relevant that the OS maps from 1890 to 1929 all

show a feature which ran along the full extent of the boundary. This could be

the bank plus something else or it could be a fence. …

33. … I agree with Mr Rocks that … the lines on the OS maps

all represent the bank for that part of the field division where the bank was.

For present purposes, that does not take matters very far since it is common

ground that the bank was present in 1928.

34. What is more interesting is the continuation of the OS

line south of the terminus of the bank. I conclude that (a) from at least 1890

onwards there was a physical feature that closed off the two fields south of

the bank; (b) that it is possible that from that time onwards that feature was

a fence that also continued up the line of the bank; (c) but it is as best

equally possible – looking only at the OS maps – that the feature to the south

of the bank only occupied the space to the south of the bank.”

31.

Secondly, the judge accepted Ms Pollock’s

contention that the feature in question was most likely to have been a fence

and rejected the Oldfields’ contention that it was most likely to have been a

hedge:

“50.(a) A fence as the likely way in which the gap was sealed.

In general, I agree with this, at least to the extent that if there was an

immediate requirement to fill the gap then a fence would be the most likely way

for that to be done. …

51.(b) The surveyable feature to the south of the terminus of

the bank was most likely to have been a hedge. I have indicated above that

the OS maps show no break at the end of the bank and so something carried on

the line of the bank (or perhaps within 1.5 metres of the centre line of the

bank) to complete the separation between the two fields. I cannot find any

evidence (or common-sense) that would lead me to conclude that it was more

likely a hedge than a fence. If there was an agricultural need to close off the

field split, then it is much more likely to have been a fence than a hedge that

would have been used to meet a particular need at a particular time.”

32.

Thirdly, the judge reasoned as follows:

“53. The assertion that in 1928 there was a stock proof

fence which ran the full length of the boundary on the Rivendell side is an

issue of fact upon which the burden lies on the Claimant since it is the

Claimant who asserts the existence of the fence at that time. I am not

satisfied that it is more likely than not that such a fence existed in November

1928. Although I have taken everything raised by the parties into account,

including in detail those matters addressed above, the core of my reasoning is

as follows:

(a) On

analysis the Claimant has no persuasive evidence that a stock proof fence would

have been required along the full line of the bank in 1928. I consider that a

properly maintained bank with hedge on top could have provided a stock proof

barrier (where the bank was) sufficient for the purposes of Mr Hallett’s dairy

farming. I consider that more persuasive and relevant expert evidence than that

of Mr Maynard would have been necessary if the Claimant was to tip the balance

in her favour on this issue.

(b) The

OS maps’ line point to the existence of the bank and a feature below the bank.

This is consistent with stock proofing being performed by those features.

Although I accept Mr Maynard’s evidence that the OS could have mapped a fence

along the line of the bank and continuing to the bottom of the field in the

same way, this possibility does not prove itself absent other evidence. In

particular, in circumstances where the bank was there throughout the period.

Whether or not there was a fence at the time of any particular OS survey from

1890 onwards as well as the bank is speculation.

(c) The

1940 photograph, and to a lesser extent the 1935 enquiry letter to Mr Worth

from his solicitor, provide some limited evidence which is inconsistent with a

fence running alongside the bank. I don’t give much weight to either of these

elements but my impression of both is that they make it slightly more difficult

for the Claimant to meet her burden of proof.

(d) The

1940 photograph analysed as I have done above provides potential support for

part of the bank being stock proof in 1940. I consider that if a substantial

part of it was stock proof in 1940 then the material whole is also likely to

have been stock proof or capable of being maintained as stock proof – to the

extent required for the farmer’s purposes – in 1928. The more likely there was

a materially stock proof bank then the less likely it is that there was a stock

proof fence along the full length of the boundary.

54. I conclude that there was no stock-proof fence

along the full line of the bank at the time of the Operative Conveyance.

…

56. I

have made no finding as to what [the feature to the south of the bank] was

although I think it was most likely to be a fence limited to closing that gap.

…”

33.

Although it is not apparent from the judgment,

the judge clarified during the hearing when the judgment was handed down that

he thought that the fence in the gap would have been aligned with the centre

line of the Bank or its eastern edge, rather than its western edge.

34.

I will consider the judge’s interpretation of the

Operative Conveyance below.

The appeal court’s approach where there is a challenge

to a finding of fact

35.

The crux of the appeal is Ms Pollock’s challenge to the judge’s finding

of fact that there was no stock-proof fence to the west of the bank at the time

of the Operative Conveyance. There was no direct evidence from any witness of

fact on this question. Accordingly, the judge’s decision was based in part on the

undisputed matters set out in paragraph 4 above, in part on the evidence I have

summarised in paragraphs 12-27 above and in part on inferences drawn from the

foregoing.

36.

Counsel for Ms Pollock submitted that, in those circumstances, the

appeal court was in as good a position to resolve the disputed issue of fact as

the trial judge. I do not accept this. The judge had the advantage of seeing

and hearing two expert witnesses on this issue, namely Jon Maynard FRICS for Ms

Pollock and Michael Rocks FRICS for the Oldfields. Both experts had expertise

in (among other things) the interpretation of OS maps and aerial photographs.

On the other hand, the advantage which the judge enjoyed as a result of seeing

and hearing the experts was a somewhat limited one, because he held that key

parts of their evidence were of no weight since the experts (and Mr Maynard in

particular) had exceeded the bounds of their expertise. Moreover, the judge did

not base his decision upon an assessment of the relative expertise, credibility

or persuasiveness of the two experts. For completeness, I should add that I do

not consider that the site visit gave the judge an advantage over the appeal

court on this issue.

37.

Counsel for the Oldfields submitted that the judge’s conclusion amounted

to a multi-factorial evaluation which should be approached in a similar way to

an exercise of discretion. I do not accept this either. Although it depended on

the assessment of a number of pieces of evidence, the judge’s conclusion that

there was no stock-proof fence was a finding of primary fact, not an evaluation

of a legal standard such as negligence or obviousness.

38.

Accordingly, the appeal court should be cautious about differing from

the judge’s conclusion, but it is not necessary to be as cautious as where a

trial judge’s finding of fact is based upon an assessment of the credibility of

witnesses or where it amounts to an evaluation of a legal standard.

The appeal against the

judge’s finding of fact as to the existence of a stock-proof fence

39.

Ms Pollock does not take issue with the first and second steps in the

judge’s reasoning, but contends that he fell into error at the third stage.

Burden of proof

40.

Counsel for Ms Pollock submitted that, although the judge was

correct to say that the burden of proving her factual case lay

on Ms Pollock, he was wrong to regard that burden as

being determinative of the factual issue in this case for two reasons. First,

because the judge had infringed the principle that a court was only entitled to

resort to the burden of proof to resolve a disputed issue where,

notwithstanding that it had striven to do so, it could not reasonably make a

finding in relation to that issue: see Stephens v Cannon [20015] EWCA

Civ 222, [2005] CP 31 at [46]. Secondly, because the judge had posed the wrong

question: given the judge’s conclusions at stages one and two, the question was

not simply whether Ms Pollock had proved that there was a stock-proof

fence, it was whether the boundary consisted, in addition to the bank, of

either a long fence running along the line of the bank and filling the gap or a

short fence just filling the gap. Given that the court was

required to select between the two identified factual alternatives, the burden

of proof could not supply the answer. Put another way, a short fence could not

be said to be more probable than a long fence because of the burden of proof.

41.

Although counsel for the Oldfields did not take the point, I realised

after the hearing that these submissions were not open to counsel for Ms

Pollock, because Snowden J refused permission to appeal on the ground that the

judge erred in determining the factual dispute by reference to the burden of

proof. Accordingly, the judge’s conclusion cannot be disturbed on this basis.

42.

On the other hand, Snowden J did grant permission on the ground that the

judge was wrong to conclude on the balance of probabilities that the boundary in

1928 consisted of the bank plus a short fence in the gap and should have

concluded that it consisted of the bank plus a long fence alongside the bank

and filling the gap. This requires consideration of what evidence there was to

support the former possibility and what evidence there was to support the

latter possibility.

Evidence for a short fence

43.

The judge only identified two pieces of evidence as positively supporting

the proposition that the boundary consisted of the bank plus a short fence in

the gap, namely the 1935 letter ([53(c)]) and the 1940 photograph ([53(c) and

(d)]). Counsel for Ms Pollock acknowledged that the reference to the “1935”

letter was probably a typographical error, and that the intended reference was

to the 1936 letter. Counsel for Ms Pollock submitted that the judge misinterpreted

these documents and that they did not provide any support for the proposition

that the boundary consisted of the bank plus a short fence in the gap.

44.

The 1936 letter.

Counsel for Ms Pollock submitted that the judge was

wrong to conclude that the 1936 letter provided any support for the existence

of a short fence as opposed to a long fence. That letter merely relayed Mrs

O’Donnell’s solicitors’ question as to whether the easterly hedge was owned by

Mr Worth. Mrs O’Donnell’ solicitors might have asked the question even if there

had been a fence running alongside the bank at the time. I agree with this.

Thus the 1936 letter is neutral.

45.

The 1940 photograph. The judge’s analysis of the 1940 photograph

was as follows:

“36. The

earliest photograph the parties have found which provides any relevant evidence

is dated 18 August 1940. It is part of an RAF photographic survey, Mr Maynard

was asked about this photograph in cross-examination and stated his opinion

that there was a hedge running south from the end of the bank. It was also his

view that the hedge might have been self-seeding as a result of there being a

fence in that location which provided an impediment to allow plants to grow. In

re-examination, Mr Maynard said that the presumed hedge that can be seen in the

1940 photograph appeared quite young. I agree with that conclusion.

37. Mr

Maynard considered that it was apparent that the feature was coming off the

west side of the bank. He was questioned about this and I do not consider that

his conclusion is supported by the photograph. I do not think it possible to be

determinative as to where the feature lies relative to the sides of the bank

because the sides and end of the bank are obscured by tree canopies, Mr Maynard

accepted that because of this he could not be certain. The qualification to the

opinion was appropriate and means that I do not give that opinion any weight. I

am not in a position on the evidence to make any reliable assumptions about the

agricultural management of the end of the bank and the end of the fence -

plainly something would need to be done to ensure a gap was not left but beyond

that 1 cannot safely go.

38. In

summary the 1940 photograph shows a feature between the end of the bank and the

end of the field division. There is no evidence of a fence along the field line

separate from the bank and the presumed hedge but this does not mean that such

a fence was not there since it was common ground between the experts that the

nature of the photograph would not necessarily show fences. There are obvious

fence / hedge lines dividing the residential land carved out since 1928 from

the agricultural land (e.g. the triangle of Field 170 that had been acquired by

the predecessor of Rivendell in 1936 and the domestic property built into the

north-west corner of Field 170). The most that can be concluded is that if

there was a post and barbed wire type fence (or equivalent) running close to

the west side of the bank then the photo would not necessarily show it.

39. However,

I consider the presence of the presumed hedge between the bank and the field end

is inconsistent with the existence of another fence in 1940 which ran the whole

length of the boundary and had done for many years. This is because of the

combination of two factors: (a) I can see no practical purpose in plugging the

gap (by a fence) if there was a fence that was already doing that job; and (b)

if Mr Maynard was correct about the self-seeded hedge then the youth of that

hedge indicates that the presence of the fence which caused it was also recent.

40. So

I can infer from the 1940 photograph that it is more consistent with there not

being an established fence along the full length of the boundary. This

inference would survive my being wrong to reject Mr Maynard’s assertion about

the line of the fence which is apparent coming from the west face of the bank

because the inference depends on Mr Maynard’s assertion about the relative

youth of the hedge more than the position of the fence in the gap relative to

the southern terminus of the bank.

41. This

tentative conclusion about the 1940 photograph also allows me to conclude on

the balance of probabilities that at least in 1940 the bank plus the hedging

growing on it was capable of providing a stock proof barrier. I bear in mind

that this was less of the bank than would have been required to perform the

same function in 1928 because the north eastern part of Field 170 had become

domestic in 1936.”

46.

Counsel for Ms Pollock submitted that the judge had made a number of

errors here.

47.

First, he submitted that the judge had mischaracterised Mr Maynard’s

evidence since Mr Maynard had not opined that the hedge in the gap was

self-seeded. In paragraph 3.24.1 of his report Mr Maynard said he had only seen

a poor-quality photocopy of the 1940 photograph, but it did not appear to show

anything different in the relevant area to the 1946 photograph. In paragraph

3.25.3(g) he interpreted the feature in the gap that can be seen in the 1946

photograph as a lonicera hedge that was aligned to the western side of the

hedge on the bank. In paragraph 7.5.20 he said that lonicera was associated

with residential rather than agricultural use. When he was cross-examined about

the 1940 photograph, however, Mr Maynard volunteered that the hedge might have

been self-seeded and grown up through a fence, although it could also have been

deliberately planted on the eastern side of a fence. He was not prepared to say

that the former was likely, but he said that it was possible. Accordingly, I

consider that the judge’s summary of Mr Maynard’s evidence at [36] was accurate

so far as it went, but it omitted Mr Maynard’s point that the hedge could also have

been deliberately planted on the eastern side of a fence.

48.

Secondly, counsel submitted that the judge’s conclusion that the hedge

and any fence within it were aligned, not with the western edge of the bank,

but its centre line or eastern edge was self-contradictory and wrong. The judge

concluded at [37] that the 1940 photograph did not support Mr Maynard’s opinion

that the hedge was aligned with the western edge of the bank. But in that case

it is difficult to see on what basis the judge concluded, as he said he did during

the handing down hearing, that the fence was aligned with the centre line or

eastern edge. I would add that, as I have pointed out above, in his report Mr

Maynard’s opinion as to the alignment of the hedge was in fact based on the

1946 photograph, which is clearer than the 1940 photograph in this respect and

in my view does provide support for Mr Maynard’s opinion. The judge does not

refer to the 1946 photograph in his judgment. As the judge correctly noted at [40],

however, this error does not affect his conclusion with regard to the nature of

the fence.

49.

Thirdly, counsel pointed out that the judge had correctly recorded at

[38] that it was common ground between the experts that, although the 1940

photograph did not show a fence separate from the bank, that did not mean that

such a fence was not there since the photograph would not necessarily show a fence.

Counsel submitted that that ought to have been the end of the point so far as

the 1940 photograph was concerned.

50.

This submission requires consideration of the reasons which the judge

gave at [39] for concluding otherwise. His first reason was that there would be

no practical purpose in filling the gap with a short fence if there was already

a long fence there. In my view this reason is flawed because it was not Ms

Pollock’s case that there was both a long fence and a short fence. Her case was

that there was just a long fence in 1928 and that a lonicera hedge had been

planted alongside it in the gap subsequently after the construction of Kaduna.

Moreover, Mr Maynard’s evidence was supportive of that case although he

acknowledged the possibility that the hedge had self-seeded and grown through a

fence in the gap.

51.

The judge’s second reason depends upon the supposition that the hedge

was self-seeded and had grown through a fence in the gap. As I have already

noted, however, Mr Maynard merely acknowledged that this was a possibility.

52.

In my judgment, therefore, the 1940 photograph is neutral with regard to

the question of whether there was a long fence or a short fence (as is the 1946

photograph).

53.

The bank and hedge as a stock-proof barrier. It can be seen from

his judgment at [53(a) and (d)] that an important part of the judge’s reasoning

was his finding that “a properly maintained bank with hedge on top could have

provided a stock proof barrier … sufficient for the purposes of Mr Hallett’s dairy

farming”. The judge considered that this made it less likely that there was a

stock-proof fence along the full length of the boundary.

54.

Counsel for Ms Pollock pointed out that, at [47(a) and (b)] and at

[53(a)], the judge had considered whether what he variously referred to as a

“suitably managed hedge”, “maintained hedge” and “properly maintained bank with

hedge” would have been stock proof. It was neither party’s case that there was

a suitably managed or maintained hedge on top of the bank, however, nor did

either expert suggest this. In any event, the judge did not make any finding

that there was a suitably managed or maintained hedge on top of the bank, and

at the handing down hearing he expressly disavowed having done so.

55.

Counsel for Ms Pollock submitted that, applying the judge’s own logic,

the bank by itself was not a stock-proof barrier in 1928. Far from being a

point which militated against Ms Pollock’s case, this was a point which

supported her case that something else was required to make the bank stock

proof. I agree with this analysis.

Evidence for a long fence

56.

Counsel for Ms Pollock identified six pieces of evidence as supporting

the proposition that the boundary consisted of a full-length fence in addition

to the bank. I will consider them in turn.

57.

The size and shape of the bank. The judge found at [27] that the

height of the bank was about 65-85 cm from the Rivendell side and about 140-155

cm from the Kaduna side and that the slope facing Rivendell was vertical and

the slope facing Kaduna was steep and concave. Moreover, the plans drawn up by

the experts show that it tapers down to nothing at the southern end.

Accordingly, counsel submitted that the judge was right to conclude, as

discussed in paragraphs 54-55 above, that the bank itself could not have been stock

proof. Something more was required, and the obvious candidate was a fence.

Moreover, a fence would fill the gap at the southern end, making that stock proof

as well.

58.

The 1936 Conveyance. Counsel submitted that the likely

explanation for the covenant extracted from Mrs O’Donnell was that there were

already stock-proof fences running along the northern and eastern boundaries of

Field 170 and that Mrs O’Donnell was required to connect the new fence to the

existing fences at either end. If there was no existing fence, Mrs O’Donnell would

at least have had to secure the new fence to the flank of the bank, and if the

legal boundary was on the eastern side of the bank, to run the new fence over

the bank to that side. That was highly improbable. The judge did not address

this point in the judgment. I agree that it supports Ms Pollock’s case.

59.

Keeping animals off the bank. Counsel for Ms Pollock relied upon

the evidence of Mr Rocks in a joint statement by the experts that stock-proof

fences “are normally erected where a boundary feature in place is not

sufficient or to prevent stock grazing on poisonous shrubs on a boundary”.

Counsel told me that Mr Maynard agreed with this, although he did not show me

any passage in his evidence on the point. The judge held (at [50(f)]) that this

was a matter which was outside the expertise of the experts. I am unclear as to

why, however. Both experts were experts on boundaries, and both had worked for

OS. I would have thought that the general reasons why fences were erected was a

matter within their expertise.

60.

The judge also said that Mr Rocks had been talking generally, and not

saying that any particular boundary would be a danger to livestock. As I

understand it, the point the judge was making was that there was no evidence

(whether from Mr Rocks or anyone else) that the bank had poisonous shrubs on it

at any relevant time. Counsel for Ms Pollock submitted that this missed the

point: a farmer would not necessarily know what plants were present and

therefore would be likely to take the precaution of erecting a fence. I accept

this argument, but in my view it adds little to the point that the bank on its

own would not have been stock proof.

61.

Alignment to the western edge of the bank. Counsel for Ms Pollock

submitted that only a full-length fence aligned to the western edge of the bank

would prevent animals from walking up and onto the bank from its southern

tapered slope and causing themselves injury or escaping. In my view this is

simply a repetition of the point that the bank on its own was not stock proof.

62.

1890 and 1909 photographs and auction particulars. Counsel for Ms

Pollock submitted that the 1890 and 1909 photographs showed pasture fields

bounded by stock-proof fences even where hedges lay behind. As I read the

judgment, the judge accepted that stock-proof fences were in use in the area at

the time. As he held, however, the question is whether there was a stock-proof

fence in the relevant location. Similarly, counsel for Ms Pollock relied upon

the auction particulars as showing that some of the lots had boundary fences,

but the answer is the same.

63.

More recent farming practice. Counsel for Ms Pollock relied upon

the evidence summarised in paragraph 27 above and submitted that it was to be

inferred that Mr Hallett would also have maintained a stock-proof fence

alongside the bank. The judge held at [50(e)] that this evidence was too remote

in time; that the evidence suggested that the problem was the lower end where

there was no bank; and that, most significantly, he could not draw any useful

comparison between sheep and dairy cattle.

64.

Counsel for Ms Pollock criticised this reasoning firstly on the ground that

the judge gave no reason for finding that only cattle had been farmed in 1928.

This is not correct: it is clear from what the judge said at [44] that his

finding was based on the reference to a cowstall with 17 tyings in the auction

particulars. Counsel submitted secondly that, if that was the basis, it was

insufficient. Counsel accepted that the auction particulars made it probable

that cattle had been kept in one or more of the surrounding fields, but

submitted that they did not show that cattle had been kept in Field 170. That

is a valid point so far as it goes, but nevertheless there is no evidence that

Mr Hallett kept sheep in Field 170 (or anywhere else).

65.

The real point is counsel’s third one, namely that there is no reason to

suppose that the bank would have been more effective as a barrier to cattle

than to sheep. Thus in my view the recent practice does lend some modest

support to the proposition that there was a stock-proof fence in 1928.

Conclusion

66.

In my judgment the evidence establishes that it is more probable than

not that there was a stock-proof fence running the length of the bank and the

gap in 1928. I therefore respectfully disagree with the conclusion reached by

the judge.

Interpretation of the Operative Conveyance

67.

The judge’s interpretation of the Operative Conveyance was based

on his finding that there was no stock-proof fence along the line of the bank

and the gap in 1928. Counsel for Ms Pollock submitted that, if

there was a full-length fence in place in 1928 as I have concluded, it must

mark the legal boundary for the following reasons.

68.

First, the reasonable reader of the

Operative Conveyance standing in Field 170, plan in hand,

would see a stock-proof fence running the full length of the boundary and a bank

behind it running along part only of that boundary. The fence would therefore

be the only candidate to be the feature represented by the continuous line

shown on plan. The conclusion that the fence is the legal boundary is the obvious

one to draw. Moreover, both experts agreed that, if there was a stock-proof

fence, the fence was the boundary.

69.

Secondly, the reasonable man would be fortified

in that conclusion by the auction particulars, which state that what was being

purchased was a “pasture field”. The fence marks the limits of the land used

for pasture purposes and it is therefore entirely unsurprising that the fence

should be constituted as the dividing line. The reasonable man would also be

mindful that the bank was of no practical use to the purchaser of a pasture

field (on the contrary it would be little more than a maintenance burden), and

therefore there was no reason why the bank should not be intended to go to the

new owner of Field 174.

70.

I accept these submissions. The judge said at [58]-[59] that he was not

sure that he would have accepted that the stock-proof fence formed the boundary

even if one was there in 1928 because it depended on the nature of the fence. I

do not see what difference this would have made, however. Whatever the precise

nature of the stock-proof fence, it would have been the only topographical

feature that corresponded to the line on the plan.

71.

Accordingly, I conclude that the stock-proof fence marked the legal

boundary in 1928. It follows that the boundary now lies to the west of bank, as

Ms Pollock contends, and not to the east of the bank, as the Oldfields

contend.

Conclusion

72.

For the reasons given above, the appeal is allowed. There will be

judgment for Ms Pollock for damages in the sum of £22,500. I will hear counsel

as to consequential matters if they cannot be agreed.