B e f o r e :

MR JUSTICE CONSTABLE

____________________

Between:

| |

Assensus Limiited |

Claimant

|

| |

- and -

|

|

| |

Wirsol Energy Limited |

Defendant

|

____________________

Arfan Khan (instructed by iLaw Solicitors Ltd) for the Claimant

Joanne Box (instructed by Cripps LLP) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 4, 5, 6, 10 February 2025

____________________

HTML VERSION OF JUDGMENT�

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

This judgment was handed down by the Judge remotely by circulation to the parties' representatives by email and release to The National Archives. The date and time for hand-down is deemed to be 10:30 on Wednesday 26TH of February 2025.

Mr Justice Constable:

Introduction

- Cleve Hill Solar Park is a solar and energy storage park situated on the north Kent coast. The site is located one mile northeast of Faversham, 3 miles west of Whitstable and situated closest to the village of Graveney. According to its website, when built, its 350-megawatt (MW) capacity could provide enough affordable and clean electricity to power over 102,000 homes. The project will comprise of an array of over 550,000 solar photovoltaic modules, energy storage and associated development infrastructure. Due to the capacity of the solar park exceeding 50MW, the project is classified as a Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project ('NSIP') and was granted development consent by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in May 2020 ('DCO').

- The Claimant, Assensus Limited ('Assensus'), is a limited company through which Mr McCarthy provided property related consultancy services. Mr McCarthy is the sole director and shareholder. The Defendant, Wirsol Energy Limited ('Wirsol'), is a subsidiary of STARVERT Energy GmbH (formerly Wircon GmbH ('Wircon')), a renewable energy group, and was engaged in the business of developing solar parks. The principal claim advanced by Assensus is a contractual claim for a bonus payment of £2,445,100 plus VAT said to be due in respect of the services provided through Mr McCarthy in respect of the development of the solar park at Cleve Hill ('the Cleve Hill Project'). The contractual claim is based upon terms alleged to have been agreed in 2014 by which Assensus was entitled to a bonus of £7,000/megawatt (or MW) upon the achievement of planning permission. Wirsol denies the basis of the alleged contractual entitlement, and argues that, in any event, any agreement reached in 2014 was long since superseded by other contractual arrangements by the time the bonus became allegedly due in 2021. In the alternative, it is claimed that Assensus is due, pursuant to an express term, a bonus which, it is to be implied, would be a reasonable one. By amendment, in the circumstances described further below, Assensus alleged the existence of an implied term to the same effect in such other contract arrangement as Wirsol may establish, and an estoppel. A further alternative claim is made for a claim in restitution on the basis of unjust enrichment. Assensus claims that £2,445,100 plus VAT is a reasonable sum or the amount by which Wirsol has been unjustly enriched. These claims, too, are denied in principle. Even if any such entitlement exists, on the alternative basis, Wirsol contends that the claimed sum is grossly inflated and far greater than the market value of Assensus' services.

- There are also two smaller claims: for damages (quantified at £205,740.92 plus VAT) for unlawful termination; and for statutory interest said to be due on a particular invoice (in the sum of £21,589.27 and continuing). Wirsol also denies these claims in their entirety.

- In a hearing over 6 days, including submissions, I heard factual evidence from Mr McCarthy, and Mr Stephen Brennan for the Claimant, who relies in addition upon the witness statement of Ms Emily Marshall, of whom no questions were asked. The Defendant called Mr Schunter. I heard from Mr Kriete and Mr Rigby by way of expert evidence in respect of the value of services provided by Assensus. As well as serving their respective reports, the experts have provided the Court with a Joint Report.

- As detailed later in this Judgment, there was an application to amend by the Defendant which, ultimately, was not contested. The Claimant sought to introduce an Amended Reply following oral reply closing submissions. That application is contested.

The proper approach to assessing the factual evidence

- The agreement upon which the primary claim is based dates from 2014, over a decade ago. Ms Box, for the Defendant, relied upon the oft-cited passage from Gestmin SGPS SA v Credit Suisse (UK) Limited [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm) in which Leggatt J (as he then was) explained at [22]:

"the best approach for a judge to adopt in the trial of a commercial case is, in my view, to place little if any reliance at all on witnesses' recollections of what was said in meetings and conversations, and to base factual findings on inferences drawn from the documentary evidence and known or probable facts. This does not mean that oral testimony serves no useful purpose – though its utility is often disproportionate to its length. But its value lies largely, as I see it, in the opportunity which cross-examination affords to subject the documentary record to critical scrutiny and to gauge the personality, motivations and working practices of a witness, rather than in testimony of what the witness recalls of particular conversations and events. Above all, it is important to avoid the fallacy of supposing that, because a witness has confidence in his or her recollection and is honest, evidence based on that recollection provides any reliable guide to the truth."

- As explained in the preceding paragraphs of the same judgment, this conclusion was drawn from what was then (and the more so now) significant psychological research into the fallibility of memory, which has exposed the lack of necessary correlation between the confidence or vividness with which a memory may be recalled and its accuracy, as well as identifying the conscious or subconscious biases to which a recollection may be subjected during the processes involved in preparation for civil litigation. As Ms Box correctly points out, this analysis has been adopted and applied in a very large number of cases and, as set out in Phipson on Evidence (20th Ed) at [45-14], 'these observations have found widespread support, not just by judges but also psychologists.'

- Recent judgments, citing Popplewell LJ's COMBAR lecture ('Judging Truth from Memory: The Science'), make clear that faulty encoding or unconscious bias can also affect the way in which contemporaneous documents might be framed such that, whilst an extremely valuable source of evidence, they do not demand uncritical primacy. As such, the contents of documents must also be tested against the facts in their full context (see Tata v DBS [2024] EWHC 1185 (TCC); and Jaffe v Greybull Capital LLP [2024] EWHC 2534 (Comm)). Of course, these cases by no means represent a full-throated rowing back from Gestmin, but merely add some nuance to the consideration the Court must give to weighing all of the evidence before it in order to determine, on the balance of probability, where the truth lies. I therefore bear this in mind whilst considering the contemporaneous documents and the witness evidence I have heard during which those documents were explored.

The Factual Witnesses

- The principal witness to give evidence for the Claimant was Mr Simon McCarthy. Whilst on the whole I accept that Mr McCarthy was not consciously seeking to mislead the Court, it was noticeable that he rarely sought to answer straight forward questions directly. He would often fail to answer the question at all (at least at first), or answer a question which had not been asked. It was unusual for Mr McCarthy to resist providing what he thought was a helpful 'commentary' around his answers, which more often than not was a pseudo-submission or gloss aimed at supporting Assensus's case. In relation to key areas of dispute, and in particular where his recollection did not accord with the written record or seemed somewhat improbable in light of what was, or more often was not, said by him at the time in writing, I have regrettably had to approach Mr McCarthy's written and oral evidence with considerable caution.

- The Claimant also relied upon the evidence of Mr Brennan, who is the Managing Director of Hive Energy Limited ('Hive'). Mr Brennan gave evidence of the nature and quality of work Mr McCarthy undertook on the Cleve Hill Project (largely not in dispute) and his own remuneration with Hive (largely irrelevant). He was a perfectly straight forward witness who gave clear answers. The Claimant also relied upon the witness statement of Emily Marshall, who again gave general evidence about what Mr McCarthy did for the Cleve Hill Project, and the Defendant did not seek to ask her any questions.

- The only witness to give evidence on behalf of the Defendant was Mr Simon Schunter, a director of the Defendant and Head of Project Controlling at the Defendant's parent company. He had no direct knowledge of the early interaction between the Mr McCarthy and the Defendant (much of which was channelled through Mr Mark Hogan, the Managing Director of Wirsol at the relevant time, but who is no longer employed by the Defendant and who did not give evidence). The evidence Mr Schunter gave about the later negotiations around potential remuneration for Assensus on Cleve Hill was given in a clear, focussed and direct way. I do not doubt the accuracy or honesty of his oral testimony.

The Facts

- From early 2014 onwards Mr McCarthy worked with a company named Wirsol Solar UK Limited, of which Mr Hogan was also Managing Director. In around August 2014, Mr Hogan sought to involve Mr McCarthy in the provision of services to Wirsol. At this stage, Wirsol was seeking to identify solar parks for development.

- As Mr McCarthy accepted in evidence, in 2014 the focus of discussions was the development of solar parks with capacity of 5MW or less. The reason behind this capacity limitation, as Mr McCarthy was aware, was that, in May 2014, the UK Government had announced that Renewable Obligation Certificates ("ROCs") would be issued only for solar parks with capacity of 5MW or less. ROCs are issued to operators of accredited renewable generating stations for the eligible renewable electricity they generate, and operators can trade ROCs with other parties or sell them directly to a supplier, and are in effect a form of subsidy. The subsidy was going to reduce over time: 1.4 ROCs per MWh would be issued for schemes which were accredited before 1 April 2015, 1.3 ROCs per MWh for schemes accredited before 1 April 2016, and 1.2 ROCs per MWh for schemes accredited before 1 April 2017.

- Mr McCarthy accepted that other types of projects were not expressly contemplated in any of the discussions he had with Mr Hogan at this time. This is consistent with the fact that there is no documentary evidence suggesting that the discussions between Mr McCarthy and Mr Hogan either before or after the email of 28 August 2014, referred to below, extended beyond the limited capacity, ROC-subsidy based developments. Whilst Mr McCarthy gave general evidence that Mr Hogan's experience and interests were broad, and that Mr Hogan's appetite for entrepreneurial involvement in all sorts of projects should they arise would have extended to non-subsidy developments, I reject the implicit suggestion that the context of the contractual discussions at the time reflected a broad and general scope of projects. Consistent with the 28 August 2014 email I now turn to, the discussions were centred upon the ROC subsidy sites.

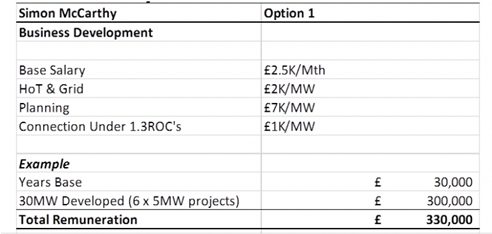

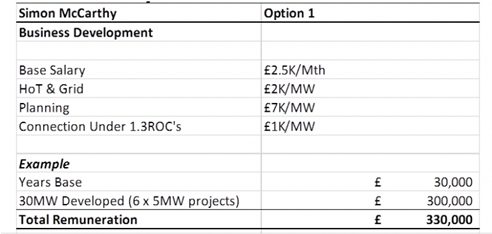

- On 28 August 2014, Mr Hogan sent an email to Mr McCarthy from his personal 'Gmail' account with the subject "Provisional Terms" (the "August 2014 Email"). That email stated:

Hi Simon –

Please take a look at the 3 options that I have considered below, have a think about what would suit you. Option 2 would require additional duties from you such as pre- commencement work on the project pipeline that we are building. This won't attract incentives but will take time and will help the business, hence the additional monthly base.

Kind regards - Hogie

- It is this email that lies at the heart of Assensus's claim. Mr McCarthy's evidence is that he accepted 'Option 2'. His witness statement stated as follows:

'Subsequent to the 28 August 2014 e-mail, I had a conversation with Mr Hogan where we discussed the options on offer. Option 2 was my preference and we discussed the provision of planning support for consented projects that were due to be constructed as per this option. Mr Hogan said that the "Base Salary" would be reviewed over time as Wirsol's business grew. I then agreed to Option 2. Wirsol and Assensus did not execute a comprehensive written consultancy agreement at the time, it was not how Mr Hogan worked….

In the same conversation with Mr Hogan, I then proposed a "sign-on" fee for Assensus. Mr Hogan said this was not something that his German colleagues would accept. Notwithstanding this, he was sympathetic to the request as he acknowledged that I had continued to develop client relationships during August 2014. On that basis, Mr Hogan suggested Assensus should bill half a month's consultancy services for August 2014 (i.e. an additional £1,500). As agreed then, Assensus' first invoice 104, 9 October 2014, (SJM1-82-83), was for:

"Consultancy Services August & September 2014 £4500.00"'

- I accept that such a telephone call took place in broadly the terms indicated. I note, however, Mr McCarthy's evidence (in his oral evidence; this was not mentioned in his witness statements) was that 'Option 3' was intended to include an obligation upon him sub-contracting and paying for all necessary consultants (planning, legal etc) out of his own pocket as a 'one stop shop' service to Wirsol. It is certainly not possible to discern this from the words used in the email or table, and one would have expected such a significant and onerous distinction between the Options to have been made explicit. This is particularly so where the email is careful to identify the extra obligations (at least in general terms) expected under Option 2 over Option 1. Mr McCarthy's recollection in this respect seems, therefore, somewhat improbable. It seems much more likely that the increased potential 'bonus' under Option 3 simply reflected the absence of a retainer. Whilst nothing specific turns on this, given that no party suggests Option 3 was selected, it gives cause to reflect upon the reliability of Mr McCarthy's recollection.

- There is no dispute that a formal written contract was not produced or executed based on this email. Although the pleaded Defence suggested that no agreement arose out of the exchange of emails and/or conversation and/or subsequent conduct, Ms Box realistically accepted in Opening that from this point on there was an agreement of some sort in place between Mr McCarthy and Wirsol entitling Mr McCarthy to payment for his services. The questions for the Court are what the terms of that agreement are and whether the terms agreed by reference to the August 2014 email were subsequently superseded. To this I will return after setting out the relevant events which follow, as I find them to be.

- Assensus submitted invoices for a monthly fee of £3000 for each of October and November 2014. There was, in addition, an ad hoc bonus of £500 in October 2014 in relation to the negotiation of the Arundel lease.

- In November there was an email exchange in which Mr Hogan sought to put down some objectives, seeking regular updates. The hope expressed was for '3-4 projects in planning by end of January …so we need 30 MW of projects with planning by end of April'. In response to Mr McCarthy's update, Mr Hogan said on 13 November 2014, 'Lets get going 30MW or even 20MW by April….'. Mr McCarthy accepted in evidence that this was a reference to 6 or 4 of the 5MW projects.

- On 9 December 2014, Mr Hogan sent Mr McCarthy an email with the subject "Invoice and Terms" which stated:

"Hi Simon –

Sorry to be sending this mail whilst on your sick bed. I am afraid I need to ask you to amend the last invoice to £2.5K retainer as the £3K was designed for you playing a more active role in the projects. This hasn't happened and I think its best we concentrate on the projects before us, which I have to say are sparse. With regards projects developed from BSES leads, these will have a compensation of 50% of normal rates as I have to pay BSES and the lead wasn't generated internally. We can talk this through on Thursday, but I trust you will both understand and see the need for speed as time is ticking on!

Please resend your invoice…… Thanks

Kind regards,

Mark Hogan"

- Mr McCarthy responded by proposing that they "let this one go and then revert to £2.5k going forward". He agreed that 50% was "totally fair" "with regard to the BSES sites". Mr Hogan agreed to "let this one go". Invoices for a monthly fee of £2500 were then submitted for each of December, January, February, March and April 2015. In May, June and July 2015, Assensus reverted to invoicing a monthly fee of £3000.

- By email to Mr McCarthy on 25 August 2015 with the subject "Monthly Retainer & Bonus Structure" Mr Hogan stated as follows ('the August 2015 email')

"Hi Simon –

Just to advise, I am very happy with the work and diligence over recent weeks and months, thank you!

The next 9 months will be important to us and we will also need to build our international footprint coupled with the O&M services. I would be very happy for you to get involved in either of these over coming months. In the meantime, effective immediately and for the month of August onwards, please initiate the monthly invoicing of £3,500 plus expenses.

In addition, you are a key member to the delivery team and you will be paid a bonus of £1,500 once we obtain PAC on Roves & Elms (September) and we will pay a G59 bonus of £300/MW for all projects delivered on-time. The first two being Salhouse & Trethosa which need to be connected by 7th October 2015, thus resulting in a £3,000 bonus. The plan would be to build a minimum of 30MW over the following 6 months, thus resulting in a £9,000 bonus.

Thank you once again.

Kind regards,

Mark Hogan"

- 'G59' (and later, G99) is the regulation surrounding the connection to the National Grid, and 'G59 bonus' related to the point at which a particular project this was achieved.

- Mr McCarthy replied the same day to say "Thank you".

- The Defendant's case is that a new agreement was reached based upon this exchange relating to 'all projects' Assensus was working on from this point onwards, which superseded the terms of the agreement reached based upon the August 2014 email (whatever they were). Mr McCarthy agreed in evidence that he accepted the terms in the August 2015 email, but he stated that the agreement related only to non-greenfield sites or 'consented sites', by which he meant projects in respect of which the land already had relevant planning. He said that this did not therefore dislodge his entitlement to the planning bonus referred to in the August 2014 email insofar as it was earned by achieving planning in relation to any future project.

- When asked whether he accepted that, on any view, the connection bonus was different from the connection bonus set out in the August 2014 email, Mr McCarthy explained that whilst that was the case, this was because the bonuses in the 2014 email were 'incremental', that it was more involved in taking a project through to construction and connection, and that the connection bonus set out in the 2014 email only applied to the 1.3 ROC sites that were developed from embryonic terms. The logic of this evidence is hard to follow, and if correct would support the suggestion (contrary to the Claimant's case) that somehow each of the stages needed to be attained by the Claimant in order for the sums earned in the other stages to be due. Instead, this email sets out terms inconsistent with the August 2014 agreement, with a higher base salary and a different bonus payment regime for all projects. There is no suggestion that there existed other types of projects for which there would be other bonus regimes, although presumably (as had happened with the Arundel lease), the Defendant could always pay a bonus for other things should it wish to do so.

- Following this exchange, Assensus invoiced and was paid £3,500 a month from August 2015 onwards. Assensus invoiced and was paid a bonus of £1,000 in relation to the Roves PAC (Provisional Acceptance Certificate) and £500 in relation to the Elms PAC. Assensus was paid a 'connection bonus' of £1,500 for a number of 5MW solar parks, which the Defendant says reflected the agreement to pay a bonus of "a G59 bonus of £300/MW for all projects delivered on-time".

- Wirsol's involvement with the Cleve Hill Project began in around June 2016. On 1 August 2016, Mr Hogan sent a signed Letter of Intent to Mr Giles Redpath at Hive, the company with whom in due course the Cleve Hill Project would be developed as a Joint Venture. It would be structured through an SPV, Cleve Hill Solar Park Limited ("CHSP"), in which both Wirsol and Hive had a 50% shareholding. Although Mr McCarthy witnessed Mr Hogan's signature, the documents do not suggest that he was otherwise actively involved in the project at this time. He was not being copied into any of the Cleve Hill related emails at this stage.

- There is no dispute that the Cleve Hill Project was qualitatively and quantitively different to the 5MW projects which Wirsol had generally been involved in to date. Wirsol was not the sole owner, and responsibility for the project was shared by way of Joint Venture. Importantly, it had a far higher maximum capacity than any of Wirsol's other projects in that it was a 350MW project. None of Wirsol's other projects had a projected or actual capacity of more than 29MW.

- On 22 August 2016 ('the August 2016 email'), Mr Hogan emailed Mr McCarthy stating as follows:

"Hi Simon –

Just to confirm our meeting and the discussions thereafter

• Base salary £60,000 PA

o Paid via invoice or PAYE (TBD)

• Bonus @ £300/MWp installed and connected on time

o Adhoc incentives TBD

• Pension

o 5% of base (if PAYE)

• Vacation

o 25Days (no change)

Thanks for the discussion this morning, the shake of hands, ongoing support and unswerving commitment. Let me know what suits, re PAYE / Invoice.

Kind regards,

Mark Hogan"

- There had clearly been a discussion about whether Mr McCarthy would continue as a consultant whose services would be paid for through Assensus, or whether Mr McCarthy would become an employee. Mr McCarthy replied on the same day, stating 'I will digest tonight but NI bonus remains as agreed £600 M/W". "NI" was a reference to the sites under development in Northern Ireland. Mr Hogan responded, "Of course, and Wilbees…as said, I don't go back on my word…or commitment.' Wilbees was a reference to another project to which a higher bonus rate had been agreed to apply.

- Mr McCarthy's evidence was that the August 2016 e-mail was, when referring to bonuses, limited to G59/G99 projects under construction. He accepted however that the base salary was not so limited, and required him to work on any and all projects. This would have included the Cleve Hill Project. He also accepted that he did not raise his understanding that he was still entitled to £7,000/MW for planning in respect of Cleve Hill. This is brought into sharp relief in circumstances where Mr McCarthy did respond by making clear his understanding that the £300/MW installed and connected on time did not relate to the Northern Ireland developments on the basis of a prior agreement.

- The exchange also included 'Ad hoc incentives TBD'. This could mean incentives for other situations 'to be decided' or 'to be determined'.

- Thereafter, Assensus invoiced and was paid £5,000 a month from August 2016, which amounts to £60,000 per annum; it was paid a 'connection bonus' of £300 per MW for a number of solar parks; it was paid a 'connection bonus' of £600 per MW for the Lisburn and Carrowdore solar parks in Northern Ireland; and it was paid a "Wilbees Negotiation Bonus" of £6,292.86. It is not clear how this sum came to be agreed or calculated. Assensus was also paid an ad hoc bonus of £10,000 in relation to Project Icarus. Similarly, there is no evidence about how or when this was decided in principle or as to the sum paid.

- As the Cleve Hill Project continued during 2016, Wirsol came to consider who would be involved with the day-to-day progress of the project. A Mr Richardson had initially been tasked with liaising with Hive on Wirsol's behalf in relation to the development of the project, but in September 2016 Mr Hogan instead asked Mr McCarthy to take on a role as Wirsol's project manager. Although there is no suggestion that this document was seen by Mr McCarthy at the time, there is documentary evidence that at this point Mr Hogan indicated to Mr Redpath of Hive that he planned to offer Mr McCarthy around £500/MW incentive for 'getting this over the line'. When applied to the anticipated capacity of the Cleve Hill Project, this would have meant a bonus of £175,000, by far larger than any bonus received to date.

- Throughout 2017, work on the Cleve Hill Project progressed. In the summer of 2017, a new project was brought to the attention of Mr McCarthy, which came to be known as Project Encore. Assensus' claim for interest relates to the alleged non-payment in respect of this project. The context of Project Encore was that Wirsol had disposed of 19 solar parks to a third party, and had entered into an agreement with a company within that third party group called Rockfire Holdings Limited ('Rockfire'), later Toucan Energy Limited. Wirsol would seek to obtain Asset Life Extensions ("ALEs") for each of these solar parks and be paid a fixed amount for each ALE that was obtained within a limited time period. Bespoke proposed incentives in relation to Project Encore were subsequently circulated by Mr Hogan to Mr McCarthy and others on 16 June 2017 in the following terms:

"Good Afternoon Team Encore

As discussed earlier in the week, I would like you all to participate in project Encore which is a very important project for WEL and WIRCON. The goal is simple as is the timeline, planning / grid and leases need to be extended by 5 years across all sites sold to Rockfire (plus Barnham which will ultimately be for selfish purposes). The benefit to WEL is significant, and can be seen in attached which is £6.5m at year end. The first £2m is destined for WIRCON, the balance of £4.5m is for WEL but we must pick up all costs associated with the deal.

Lucy is working a generic pipeline tracker document which will be published next week. I know there are costs which I want to keep to a minimum but most critically the landowners may want something. So I have artificially allowed £5K/MWp payment to the landowners which equates to £535K (approx.). I don't want to spend this unless necessary but that is the "pot" and across the portfolio for every £ that is less than said "pot" 50% will go towards team Encore and 50% retained by WEL, thus you are incentivised. Furthermore there will be an incentive of £1,000 / MWp for the exercise which will be split as outlined below.

I want you to work as a team, clearly Simon and James will do the heavy lifting hence the weighting allocated as follows:

By way of example, if the team only spend £335K on landowner inducements creating a balance of £200K, then £100K will be allocated to Team Encore (Andrew will be responsible for managing and tracking). Lets also assume we have a 100% hit rate.

- Total £206,000 paid 31st December 2017 pro-rata

I will try to draw up something more formal when back from Oz, but the principle is clear and if you only spend £100K with the landowners, the pot is clearly bigger but equally WEL is also proportionally better off so WIN-WIN all round and WIRCON own 75% of WEL so they are happy too.

Please jump on this and drive toward a successful outcome and thank you!"

- Mr McCarthy's share was to be £400/MW plus a 40% cut of any 'Team' savings on the landowner inducement pot. As Mr McCarthy accepted in evidence, they were going to receive this bonus because Wirsol was going to receive payment from Rockfire. This is evidence of a specific ad hoc bonus regime being agreed between the parties on a project specific basis.

- On 28 November 2017, Mr Hogan wrote to the team on Project Encore:

"Team Encore –

Just to advise that I have agreed with Andrew that you will each be paid £5K in your year end salary/invoice which will be off-set from the balancing amount once determined.

I do have to advise that payments will be released once we have a better understanding from Rockfire, it is in all our interests to get this over the line as a bonus can only be paid upon receipt, albeit I will always be fair and equitable."

- At this stage, as Mr McCarthy accepted in evidence, it was not known what the precise figure owed to Wirsol from Rockfire would have been (although they had a rough idea). Mr McCarthy did not at the time dispute that the 'balancing amount' (i.e. the amount due to Mr McCarthy) would be released 'once determined'.

- Wirsol then invoiced Toucan on 30 December 2017 for £5,338,184 plus VAT in for the ALE works.

- On 4 January 2018, Mr Hogan again explained to Mr McCarthy that, whilst he would try to figure out another part payment in advance of receiving payment from Rockfire, the balance would have to wait until they had a better understanding of the position with Rockfire. Mr Hogan's hesitancy was no doubt because of concerns about whether and when the sum from Rockfire would be realised. Rockfire had disputed that any sum was due. Toucan issued a claim against Wirsol in the High Court on 1 October 2018, and Wirsol counterclaimed to recover the ALE payments that it said were due. The counterclaim was substantially successful, although it did not succeed in respect of one of the sites.

- At the end of February 2018, it was explained in an email to Mr McCarthy that (as had been anticipated) Rockfire had not settled their invoice 'so we will not be in a position to pay the balance of the Encore bonus this month.' However, it was explained that Mr Hogan had approved a further payment, effectively on account, of £5,000. Mr McCarthy was told he could therefore add this to his monthly invoice, which he did. A further £5,000 payment was made in March 2018, so that by this time £15,000 had been paid (but not invoiced).

- On 20 April 2018, Assensus then submitted an invoice (No 176) for £95,340 plus VAT, the entire sum due on Project Encore. On the face of invoice No 176, no credit was given for the previous on-account payments of £5,000 referred to in the exchanges above. At the same time, Mr McCarthy submitted a 'Request for Payment', the covering email for which stated, 'As agreed a £15k + VAT'. The Request for Payment itself stated that it was 'Re Invoice 176'. This is shown in Mr McCarthy's schedule of payments as 'Paid' on 24 April 2018. It is not entirely clear if Mr McCarthy was paid this sum in three £5,000 sums in the preceding months (with the invoicing/payment request catching up), or was only actually paid this sum on 24 April 2018. It does not matter to the legal analysis which it is.

- Mr McCarthy suggested in evidence that what was 'agreed' was only the fact that he would be submitting an invoice to Wirsol; not an agreement that the payment request would be for £15,000. He suggested that the sum was simply what Wirsol had said it could pay. Against the background of the fact that the bonus represented Mr McCarthy's share of sums received from Rockfire (and none had been received), and against the previous communications about the release of sums being dependent upon resolution of the position with Rockfire, to which Mr McCarthy had raised no objections, I consider it more likely that Mr McCarthy did in fact agree that the only payment at that point due from Wirsol was such advances as they agreed from time to time to make, until the dispute with Rockfire was resolved. This conclusion is entirely consistent with Mr McCarthy's candid evidence that sums would not be due to him in respect of such parts of the claim against Rockfire which failed, and that he would need to amend his invoice in respect of any sites where the claim against Rockfire was unsuccessful. Indeed, ultimately the sum paid by Wirsol to Mr McCarthy in respect of Project Encore was £91,840 instead of the invoiced £95,350 because the claim against Rockfire in respect of one of the sites failed (and therefore Mr McCarthy's bonus was £3,500 lower). There is no claim for this sum or suggestion that it was due irrespective of the failure of the claim against Rockfire.

- Returning to the broader picture, on 29 January 2018, Mr Hogan wrote to Assensus in respect of its remuneration ("the January 2018 email"):

"I want to advise that I do appreciate your good work, we will seek to address further forms of compensation through 2018 as the business matures which will include inclusion in an IPO equity pot for certain members of the WEL team North and South (assuming I get agreement with Germany). I also appreciate your work on Cleve Hill and of course the Encore and NIE projects in 2017. Effective from 1st Jan 2018 you can invoice us based on £72K PA, whilst this is below our conversation, as said, I will seek to create value for you which gives upside to you and WEL accordingly. I believe I have demonstrated this previously and will continue to do so.

Keep up the good work and thank you – happy to have an off-line chat albeit this week is already a mess. Please keep this confidential as there is a delta with "others."

- Mr McCarthy accepted that this would have followed a discussion with Mr Hogan, but stated that he could not recall the conversation about a potential IPO equity. There is no record of Mr McCarthy querying the fact that the further forms of compensation referred to, including a potential equity pot, required agreement 'with Germany' (i.e. the directors/shareholders of parent company, Wircon). When it was put to Mr McCarthy that this was Mr Hogan explaining that directors would need to sign off such further forms of remuneration, Mr McCarthy unconvincingly 'clarified' that that requirement was limited to the potential IPO equity pot, notwithstanding that he had stated he could not recollect the conversation. The email is plainly not so limited, and states in terms that agreement with Germany was required in respect of 'further forms of compensation' including the potential IPO equity. Objectively, it is obvious that it was being made clear that any bonus, at least of financial significance, needed to be authorised 'with Germany'.

- During this time Mr McCarthy was working predominantly on the Cleve Hill Project. Assensus invoiced and Wirsol paid a monthly fee of £6000 throughout 2018 (with an ad hoc £2,000 bonus at Christmas 2018), through to May 2019.

- On 7 September 2018, Mr Hogan arranged a corporate entertainment trip to Goodwood Revival. As Mr McCarthy described in evidence, the date started in the morning at 10am at Mr Hogan's house where a 'a plentiful supply of champagne was served'. Mr McCarthy said that at lunch, by then at Goodwood, Mr Hogan initiated a conversation about the Cleve Hill Project bonus. Mr McCarthy's evidence continued:

"To be candid we were both rather squiffy but nonetheless I have a good recollection of the conversation: I referred to my engaged bonus terms and Mr Hogan said I would certainly be paid £1 million for all my work, I acknowledged his comments but clearly this was not the time to enter into any discussion of a variation to my engaged terms. We had a brief telephone conversation later that evening where Mr Hogan repeated our earlier conversation."

- Mr McCarthy broadly stuck to this account during oral evidence. Mr Hogan did not give evidence. His account of what happened is contained in an internal email to Mr Brückmann (CEO of Wircon) and Mr Schunter (Head of Project Controlling at Wircon) in 2020:

"During a hospitality event at Goodwood in September 2018, I mentioned to SMcC that he was doing a great job and that I would seek to increase the ultimate incentive package, we did not discuss numbers. He was very drunk and informed me that he wanted a "bar" which is slang for £1m (one million). At no stage have I ever agreed to such an incentive, not only do I not have the sole authority to do so (I would have needed Markus & Peter) but I also simply don't/didn't and never have thought that such reward was merited - far from it given he's only "managing" Cleve Hill and didn't find or create the opportunity.

My position remains unchanged - despite SMcC trying to suggest otherwise - I should note that he was thrown out of the Goodwood event due to being inebriated and I also had a subsequent sexual harassment allegation against him from that same event (see attached with subsequent allegations of unwanted phone calls and an apology). I dealt with these matters discreetly, Andrew Standing was informed and Markus / Peter too - I could have taken a much firmer line as this isn't the only instance."

- When the content of the last paragraph in this email was put to him, Mr McCarthy accepted the fact of an incident for which he apologised. The present relevance of this is to the likely level of his inebriation on the day in question. I suspect he was rather more than 'squiffy'.

- There is no correspondence (or WhatsApp messages or similar) in which Mr McCarthy ever mentions this conversation or a £1m 'offer' until the middle of 2020, which prompted Mr Hogan to set out his position, above. I have no hesitation in rejecting as unreliable the evidence that Mr Hogan 'offered' Mr McCarthy a bonus of £1m at Goodwood. If he had done so – supposedly twice on the same day - it is practically inconceivable that Mr McCarthy would not have referred to this offer at some point to Mr Hogan, whether in an email or informally on WhatsApp, during the following 18 months. Yet he does not. Other than his testimony, the only evidence that Mr McCarthy relies upon to support his claim is a letter from his accountant dated June 2024 stating that there had been a meeting nearly six years previously on 5 October 2018 in which Mr McCarthy had sought advice on the tax implications of a circa £1m payment to Assensus. There is no attendance note, or handwritten notes to support this statement, and the author of the letter did not give a witness statement or attend.

- It is quite possible that, fuelled by champagne and joire de vivre brought on by the surroundings, Mr Hogan and Mr McCarthy had 'optimistic' conversations about the future ('this time next year, we will all be millionaires…'). It might have related to the possible benefits of an IPO if Mr McCarthy obtained equity. But whatever drunken chatter there was about the potential returns on the Cleve Hill Project or other parts of the business or however Mr McCarthy has come to recollect such conversation, there was, in my judgment, plainly no genuine understanding on Mr McCarthy's part following the day at Goodwood that any or any serious 'offer', had been made of a £1m bonus, less so any agreement reached. This is so irrespective of what Mr McCarthy may or may not have said to his accountant. Furthermore, I reject as untrue the suggestion that during this drunken conversation, Mr McCarthy 'referred to my engaged bonus' (by which he meant his alleged contractual entitlement to c£2.5m based on 350MW@ £7,000 MW/p). To have done so during such a conversation, yet never to have referred to 'my engaged bonus' at any other time during the numerous exchanges about his remuneration which took place between 2014 and Assensus' invoice in 2021, is completely implausible.

- During the early months of 2019, there were further exchanges about Mr McCarthy's package. On 23 February 2019, Mr McCarthy noted in a WhatsApp message to Mr Hogan: "One final point is we really need to have our offsite catch up about my package". Mr Hogan replied:

"I knew that was coming - too obvious Sir !

Your basic package isn't changing Simon - I am happy to include UK projects outside of Cleve in your remuneration bonus.

Any "upside" on Cleve will need to be discussed with Markus / Peter and furthermore, there needs to be an element of risk. I have essentially put £3m into this which is a £750K hit if it goes wrong (25%) not to mention your time / remuneration over the 2 years which is circa £250K

Happy to have a chat and I would also suggest we wrap the Toucan planning bonus (remaining) into the discussion so that when Cleve comes through that will be taken care of too.

Please do remember that whilst you are doing a great job and you have my back, which I appreciate, there is no risk / downside to you. Also realise that I have other shareholders to contend with..... this is NOT to say that we shouldn't have a chat and get alignment - I just want to set the parameters.

Hope this all makes sense...."

- Mr Hogan is making clear that (a) no 'upside' on Cleve Hill as yet had been agreed and (b) as he had said previously in relation to further remuneration, it would need to be discussed with 'Markus/Peter' (i.e. Mr Wirth and Mr Vest, directors in Germany). He is, also, suggesting that any 'upside' would need to involve Mr McCarthy taking some 'risk', which he was not at the time (and did not, in the event, do). He was being paid £72,000pa for working largely full time on the Cleve Hill Project.

- Mr McCarthy responded, "In fairness we've been planning a formal mtg for over nine months! We've never not agreed on numbers so let's park this until you get back, but let's make sure we do have the chat!" Mr McCarthy does not suggest that he is already contractually entitled to a bonus based on the August 2014 email. Indeed, the response is completely inconsistent with such an understanding. Rather, the exchange is only consistent with an understanding that any 'upside' on Cleve Hill remained yet to be agreed.

- On 18 April 2019, Mr McCarthy sent to Mr Hogan an Agenda for the planned "Off Site Catch Up". This included:

- Cleve Hill - formalising the agreed bonus.

- Encore – outstanding £80,340.00

- Future roles and responsibilities

- The meeting took place on 26 April 2019. Following the meeting, later the same day, Mr Hogan sent the following email to Mr McCarthy (copying in Andrew Standing, the finance administrator of Wirsol) ('the April 2019 email'):

"Hi Simon –

Firstly, once again thank you for your time this morning but moreover your dedication to the cause. Secondly, as we discussed, please see below confirmation of our discussion this morning:-

- Remuneration – Effective May 1st 2019 your remuneration is increased to £80,000

PA payable monthly in arrears (as is the case currently)

o Toucan ALE, whilst I do not wish to formalise anything until the win at court, I am happy to release and deduct

⁃ £10,000 which can be invoiced immediately

⁃ £10,000 which can be invoiced end of June

- Andrew – these amounts can be deducted from the notional final payment which maybe subject to change depending on final outcome (please add to tracker)

o 65MWp Construction (Outwood / Newton / Sweeting Thorns / Low Farm).

⁃ £400/MWp paid one month after G99 on a site by site basis

With regards Cleve Hill, as discussed, I will develop a spreadsheet with a rachet mechanism increasing with value derived from the project. I will share this will you for general acceptance (which will include others in the WEL Team) prior to submission to Markus and Peter, which I must do. I will endeavour to both make this fair, represent risk and also create a real positive outcome for all parties – WIN-WIN-WIN ideally. In terms of timeline, I shall endeavour to get an excel file composed next week, we can discuss the following week when I am back from Oz and I will aim to have formal approval within the month of May – I trust that this is acceptable.

I hope that this covers the points discussed, see you shortly albeit briefly and thanks once again.

Have a great weekend

Kind regards,

Mark Hogan"

- Mr McCarthy's response was that he looked forward to receiving the Excel. It is clear that Cleve Hill formed part of the discussions referred to, but it also is clear that no incentive in respect of it was agreed. Cleve Hill is dealt with in the email after the 'Incentive' section. It can be inferred that during those discussions, Mr McCarthy made no mention of the fact that, on his understanding, the bonus due to him was already set in stone at £7,000/MWp. When it was put to Mr McCarthy that he did not point out that he had an existing entitlement to a c£2.5m bonus based on the August 2014 email, Mr McCarthy suggested that "what I think was coming down the line was a variation…" and that he thought there was a chance it might be more beneficial to him, so he didn't object. I do not accept this evidence as remotely credible.

- It might be noted, further, neither is any suggestion of an offer of a £1m bonus referred to in Mr McCarthy's response. It is obvious that the potential incentive was being discussed because both Mr McCarthy and Mr Hogan considered that there was no agreement, or extant 'offer', in place as to what it should be. The anticipated process was reaching an agreement with Mr McCarthy, and others in the Wirsol team, on what the bonus structure would be prior to submission for approval to the directors in Germany which Mr Hogan said, in terms which could not be clearer, 'I must do'.

- Both parties were treating the Cleve Hill Project bonus as something which remained to be agreed.

- Following the April 2019 email, Assensus invoiced and Wirsol paid a monthly fee of £6,666.67, consistent with the base salary set out in the April 2019 email.

- The discussions with respect to a bonus on the Cleve Hill Project continued sporadically through 2019. On 1 June 2019, in a WhatsApp exchange between Mr Hogan and Mr McCarthy, Mr McCarthy continued to press to 'get my package agreed'. The next day, the exchange continued with Mr Hogan in effect expressing frustration at being 'bugged' on this point whilst he was trying to sort numerous things, including this. Mr McCarthy responded that, 'I have been requesting an agreement for inordinately long time'. This is inconsistent with any understanding that an agreement was already in place in respect of Cleve Hill, whether by virtue of the August 2014 email, or generally.

- In emails to which Mr McCarthy was not party, but consistent with the demands from him for a resolution to the question of his remuneration on Cleve Hill, Mr Hogan attempted to agree parameters for a bonus with the directors of Wirsol/Wircon. Mr Hogan was proposing a 'bucket' of 5% of net profits based on Wirsol's 50% shareholding in CHPL, from which bonuses would then be paid. The reaction of Mr Markus Wirth, one of those directors referred to by Mr Hogan in his email to Mr McCarthy, was that 5% was appropriate. Mr Peter Vest, another director, was expressing the view that this was on the high side. This comment must be seen in light of the usual position in Germany, as explained in evidence by Mr Schunter, that bonuses are not generally paid: a person does a job for the salary they get paid, and should not expect more.

- Discussions continued internally, and towards the end of the year, it became clear to Mr Hogan that Mr McCarthy was – in light of the absence of any agreement on what the Cleve Hill Project incentive would be – planning to go above Mr Hogan and reach out to the directors in Germany. This is consistent with Mr McCarthy understanding that the decision makers lay above Mr Hogan's head. On 6 March 2020, Mr Hogan wrote to Mr Brückmann (CEO of Wircon) and Mr Schunter (Head of Project Controlling at Wircon):

"It maybe that [Mr McCarthy] tries to reach out to you guys personally circumventing me. I would ask tow things from you:

1. Remind him that he reports into me and that we (Wircon & Mark Hogan) are in discussion

2. State that any agreement will be communicated through myself

As I have told you both, Simon didn't find or create this opportunity, he's done a good job for sure. But frankly "greed" is taking over which I don't appreciate. When we win Cleve Hill it will be as a result of the JV between WEL & Hive and we win as a WEL Team – its certainly not about one person….

Hope this is OK but he's pretty pissed off right now – we need to address the open issue of the incentive – Simon lets pick this up on Monday. Happy to speak in the meantime."

- Mr McCarthy, as anticipated, emailed Mr Brückmann the same day requesting a face to face meeting. This was originally scheduled to take place on 13 March 2020, but did not take place (COVID restrictions had been imposed). Mr McCarthy's agenda included, 'Cleve Hill – My Role and Remuneration.'

- A telephone conference took place between Mr McCarthy, Mr Schunter and Mr Brückmann on 9 April 2020. Mr McCarthy produced his own minute of the call, which was not circulated for agreement. According to the minute, Mr McCarthy asserted on the call that 'Mr Hogan had agreed to pay SM a bonus of £1m' in relation to the Cleve Hill Project. As set out above, I do not accept that this happened. This was the first time Mr McCarthy appears to have mentioned this. The note records, consistent with the discussions that had been going on 'behind the scenes' between Mr Hogan and his superiors, Wircon were anticipating paying Mr McCarthy 60% of a £450,000 team bonus, i.e. £270,000. Mr McCarthy's note suggests he was 'staggered' at this. It is significant that Mr McCarthy did not mention the fact that he considered that he already had a contractual entitlement to payment of a bonus based upon £7,000/MW. Mr McCarthy's own note states, 'MB [Matthias Brückmann] asked about the nature of the agreements', by which he meant any agreement reached with Mr Hogan. This was in response to Mr McCarthy having referred to £1m. If Mr McCarthy genuinely considered that an entitlement to be paid £7,000/MW had been agreed with Mr Hogan in August 2014, it is inconceivable that he would not have raised it at this point in the meeting.

- Communications between Mr Hogan and his superiors continued, during which various options were considered for division of a team bonus for the Cleve Hill Project, based upon a 400,000 Euro pot. A further meeting then took place between Mr McCarthy, Mr Schunter and Mr Brückmann on 7 May 2020. There are two sets of minutes produced: one by Mr Shunter and an amended set produced by Mr McCarthy. There is, in addition, an email from Mr Schunter in which he comments on the changes. At this meeting, Mr McCarthy was offered a bonus of £257,000. There is no suggestion that this was agreed: Mr McCarthy was dissatisfied with this and was holding out for more.

- At the end of May 2020, the DCO was issued, which was the trigger for an entitlement to be paid a planning related bonus on the Claimant's case. No invoice was submitted by Mr McCarthy.

- On 12 June 2020, Mr McCarthy wrote requesting payment of the balance of Invoice 176 (for Project Encore) which (in light of further interim payments) was stated as £60,340 plus VAT. Mr Hogan responded refuting that any sums were due given that the final calculation of any Project Encore incentive was entirely dependent on the eventual outcome of the ongoing litigation with Rockfire/Toucan.

- On 6 July 2020, Mr McCarthy wrote to Mr Standing, copying in Mr Hogan, Mr Brückmann and others, stating:

"I believe it is now a matter of common knowledge that Wirsol Energy Limited will only continue in 2021 as an accounting, rather than operational, entity. On 7 May 2020 I met with Matthias Brückmann and Simon Shunter of Wircon GMbH (the shareholders of Wirson Energy Limited) to discuss both the exit for Cleve Hill and future engagement with Wircon GmbH (the details of which remain a matter of ongoing discussions).

Given the above, Assensus Ltd will no longer be contracting to Wirsol Energy Limited in 2021 and therefore not subject to any changes in the next tax year."

- Mr Standing then wrote to Mr McCarthy enclosing a copy of a Consultancy Agreement, saying that he had looked back through his files and could not find a copy of it which had been signed by Mr McCarthy; he asked that Mr McCarthy provide his signed copy if he had one, and if not to print, sign and return the attached agreement. Mr McCarthy replied the following day saying that he had not recalled seeing it before. There is an email dated shortly after this exchange, on 13 July 2020, in which Mr Schunter records receiving a call from 'furious' Mr McCarthy, on the basis that he had not seen it before and it had not been the subject of negotiations. It was agreed that Mr McCarthy would send his comments, which would then be reviewed and an agreed version signed in the coming weeks. In fact, whilst Mr McCarthy did mark up the agreement with his comments, he did not send them, and no agreement was ever executed. In Mr McCarthy's own, internal, mark up, he made no reference to the entitlement to £7,000/MW deriving from the August 2014 email. He also did not strike out or amend the stated 3 month notice period.

- No further discussions on the Cleve Hill Project bonus took place and no sum was agreed or paid.

- By a judgment dated 14 April 2021, Henshaw J largely rejected Toucan's claim against Wirsol, save in respect of one site. Permission to appeal was sought by Toucan but rejected by Males LJ. Following this, Mr McCarthy provided a request for payment for the outstanding sum on Invoice 176. He said, 'I recognize the original judgement excluded the Widehurst claim as being payable by Toucan to Wirsol, I am faintly aware that this site is the subject of further proceedings but I am happy to be corrected. Should Wirsol Energy Limited accept the court's decision that its Widehurst claim was without merit, then I am happy to credit this amount'. Mr McCarthy also attached 'an 'ALE Interest' spreadsheet' and stated that he was 'exercising Assensus Ltd's statutory right to claim interest (at 8% over the Bank of England base rate)' dating back to April 2018.

- On 16 September 2021, Mr McCarthy sent Invoice 218 to Mr Brückmann, Mr Schunter, Mr Hogan and Mr Standing with the following cover email:

"Dear Matthias, Simon, Mark and Andrew,

Further to the recent agreement with Hive Energy Limited for Cleve Hill Solar Park, please find attached Assensus Ltd's bill in respect of the services provided for the project to the WIRCON Group.

As stated in the bill's narrative, the £2,445,100 (exc VAT) is calculated by multiplying the agreed £7,000 per MW by the 349.3MW value of the solar array in the Candidate Design (referenced in the Development Design chapter of the Environmental Statement).

Separately, we need to discuss a payment in respect of the additional battery capacity that my efforts helped to secure for the Group. That should not however delay payment of the attached invoice, which is on the same terms as my previous invoices: NET 0. Furthermore, £72,408 (inc VAT) from Invoice 176 - 20th April 2018 + the concomitant interest remains outstanding. I would be grateful if someone from the WIRCON Group could please respond to my email from last Tuesday morning on this matter, thank you in anticipation.

Kind regards,

Simon"

- Invoice 218 (the "September 2021 Invoice") sought payment in the sum of £2,445,100 plus VAT for 'Planning and associated services for the solar array consent at Cleve Hill, Kent. £7,000 per MW x 349.3MW in the Candidate Design (as referenced in the Development Design chapter of the Environmental Statement)'. It is this invoice which is the subject of Assensus's principal claim.

- Wirsol subsequently informed Assensus that it was terminating its engagement and that it had removed Assensus's and Mr McCarthy's access to its business. Wirsol argues that there was no credible basis for Assensus to have demanded such a payment, and that the submission of a vastly inflated invoice for which there was no proper basis represented a serious breach of Assensus's contractual relationship with Wirsol justifying summary termination. Assensus was ultimately paid a further £20,000 plus VAT on a goodwill basis in or around early January 2022.

Assensus's contractual claim for a bonus

Express agreement to a bonus of £7,000/MW

- It is Assensus's case that the 'Service Agreement' entered into between it and Wirsol was part written/part oral. It claims that Wirsol was obliged to make bonus payments to Assensus in accordance with "Option 2" as set out in the August 2014 Email in respect of any greenfield solar park developments that may take place by reason of Assensus' services, i.e.:

(i) upon obtaining the Heads of Terms with a landowner nnd the securing of a grid connection, Wirsol would pay Assensus £2,000/MW of the proposed scheme's installed capacity;

(ii) upon obtaining planning permission for the development of a solar farm, Wirsol would pay Assensus £7,000/MW of the permitted capacity; and

(iii) upon qualifying for support at the rate of 1.3 ROCs (i.e. Renewable Obligation Certificates) under the support regime then in force in relation to solar parks of <5MW capacity, Wirsol would pay Assensus £1,000/MW of the installed capacity.

- Assensus further contends that in respect of any projects that took place by reason of Assensus's services but which were not greenfield developments, Wirsol would pay Assensus such bonus as was reasonable in all the circumstances, having regard to the bonuses payable for the development of greenfield sites, bearing in mind any relevant similarities and/or differences between such developments and the project in question. It is argued that the term which required Wirsol to pay a bonus in addition to the 'base salary' was express; and the term which provided that the amount would be such as was reasonable in all the circumstances was implied because it was obvious, alternatively to give business efficacy to the Services Agreement.

- A point of importance in the case as developed by Mr Khan on behalf of Assensus and as, at times, described by Mr McCarthy in his evidence was a conceptual distinction between 'greenfield' sites and 'non-greenfield' sites. In oral closing submissions, Mr Khan accepted that there is no direct evidence that this distinction was discussed as part of the oral exchanges between Mr McCarthy and Mr Hogan which gave rise to the Services Agreement for which Assensus contends. However, it is said that it may be inferred that the bonuses within the August 2014 email nevertheless related to greenfield sites. It is on this basis that Mr McCarthy then explained in evidence that the later correspondence which referred to the G59 or G99 bonuses was not relevant to greenfield site projects, of which the Cleve Hill Project was the only example.

- There is, however, no evidential basis to support a finding or inference that a distinction between greenfield projects and other projects was either discussed between Mr Hogan and Mr McCarthy in or around August 2014, or formed any part of the factual matrix against which the agreement that was reached following the August 2014 email should be construed. It is clear from Mr McCarthy's own evidence that the focus of discussions at the time was solely on subsidy earning 5MW sites being undertaken by Wirsol, irrespective of whether such potential projects could be regarded as 'greenfield' or whether they were further along the development process. The base salary plainly applied to any and all projects of this type which Wirsol asked Mr McCarthy to get involved in, or which Mr McCarthy himself identified as opportunities. Similarly, the bonuses applied without distinction between 'greenfield' or more developed projects that Wirsol was purchasing/developing with the benefit of pre-existing consents. The wording of the email expressly envisaged, in addition, that Mr McCarthy would be expected to do some work which would not attract incentives, but gave rise to an additional monthly base.

- There is no evidence that projects of the nature and size of Cleve Hill were in the contemplation of the parties at the time, in August 2014. Mr McCarthy could not recollect discussing any such large projects. Similarly, the agreement does not contemplate Wirsol acting in a Joint Venture. I find, in light of the matters which were in the contemplation of both Mr Hogan and Mr McCarthy that, as Mr McCarthy at one point said in terms, 'my engaged terms were, and as I said, I freely admit, for 1.3 ROC sites.' This is supported by the fact that 1.3 ROC was specifically identified as the last of the stages for which bonuses could be earned, and the agreement makes sense if the prior stages are construed in this context. That this is envisaged is also supported by the worked 'example' which follows, again relating to a 1.3ROC project. It might be noted that this envisaged a 'greenfield' example, in that all the stages from securing landowner agreements onwards are aggregated into the overall earnings. This itself defeats the suggestion that some important distinction between greenfield projects and 1.3ROC projects was agreed by the parties.

- It follows from this that I do not consider that the oral/written agreement formed between the parties contained a bonus regime that explicitly applied to projects of the nature of Cleve Hill, which was extremely different both in its nature and size, and also was to be a Joint Venture. There is no linguistic or contextual basis to construe the agreement formed on the basis of the August 2014 email as giving rise to an entitlement to claim £7000/MW when Cleve Hill Project reached the Development Consent Order stage.

- As set out at Section 19 of Chapter 3 in The Interpretation of Contracts (Lewison, 7th Edn), the Court may not generally look at the subsequent conduct of the parties to interpret a written agreement. However, where the agreement is partly written and partly oral, subsequent conduct may be examined for the purpose of determining what were the full terms of the contract. I have reached the conclusion set out above without looking at subsequent conduct. But, were I to do so in concluding whether the part written/part oral contract contained the express terms pleaded at paragraph 12 of the Particulars of Claim, I would find very strong support in that conduct for the conclusion that neither party remotely considered at any time that the agreement reached on the basis of the August 2014 email contained a contractual entitlement by which Mr McCarthy would be paid £7,000/MW for the Cleve Hill Project. Mr McCarthy did not refer to it at any time in his negotiations about his remuneration for Cleve Hill, notwithstanding having been asked on at least one occasion explicitly to explain the basis of any agreements reached with Mr Hogan about a Cleve Hill bonus. Mr McCarthy's suggestions that he did not do so because he wanted, effectively, to 'tread softly' in those negotiations is not remotely credible. Having seen Mr McCarthy giving evidence, it is plain to me that, had he genuinely believed that he had a binding agreement in place which entitled him to £7,000/MW for Cleve Hill, Mr McCarthy would have deployed that in the discussions he was having. All the correspondence is consistent with the conclusion that Mr McCarthy believed, rightly, that there was no agreement or structure at all in place by which a bonus for Cleve Hill could be readily calculated. This is why he was (to use Mr Hogan's term) 'bugging' the management to put something in place.

- Even if – contrary to my conclusion above – the agreement arising out of the August 2014 email did include an entitlement to be paid £7,000/MW for projects which included Cleve Hill, I consider that the 'Services Agreement' entered into in 2014 was superseded by the various agreements reached by which Mr McCarthy's overall remuneration package was changed in the following years. During this time, Mr McCarthy's base package increased significantly (far in excess of inflation) and it is unsurprising that his bonus entitlement changed as well.

- Each statement of the package for the following year was effectively an offer to renew the engagement by Wirsol on new terms which was accepted by Mr McCarthy in continuing to offer his services. It does not strictly matter if one views the analysis as a single 'Services Agreement' which came to be renewed and varied or a series of fresh agreements. The key question at each point is: what were the terms of the contractual agreement between the parties at the point at which the parties semi-regularly revisited their agreement?

- The agreement reached in 2015, in respect of bonuses, was expressly inconsistent with the alleged Services Agreement or any other agreement based on the August 2014 email. It applied, expressly, to all projects. It did not prevent Wirsol providing any other ad hoc remuneration (such as a Christmas bonus or particular work which Wirsol considered should be rewarded additionally), but there was no other express contractual entitlement on the part of Assensus in this regard. Therefore, if the year before a series of bonuses ranging from £1000/MW to £7,000/MW had been agreed and was applicable to Cleve Hill (still in the future at this point) as alleged by the Claimant, it is clear that a year on, the bonus structure on offer was significantly altered. If it applied to (the future) Cleve Hill, it would have entitled Mr McCarthy to £300/MW on connection. The 2015 terms were agreed by Mr McCarthy. Therefore, either the Services Agreement as alleged by the Claimant was superseded or, in any event, varied in such a way that the £1,000/MW to £7,000/MW range no longer formed part of any package or retainer. To the extent relevant, and for the reasons set out above, if subsequent conduct is relevant to whether and to what extent the Services Agreement was superseded or varied, that conduct strongly substantiates the fact that neither party acted in a manner consistent with a Services Agreement containing a £7,000/MW bonus applicable to Cleve Hill as alleged by the Claimant that remained extant from 2015 onwards.

- The primary way the Claimant puts its case, therefore, fails.

Express Entitlement to a Reasonable Bonus

- At paragraph 27, Assensus' pleading states: '[i]f (contrary to Assensus' primary case) the Cleve Hill Project was not a greenfield development to which 'Option 2' of the Provisional Terms Email applied, Assensus is entitled to such bonus as is reasonable pursuant to the term of the Services Agreement pleaded at paragraph 12(6) above.' Paragraph 12(6) provided that the term which required Wirsol to pay a bonus in addition to the "base salary" was express; and the term which provided that the amount would be such as was reasonable in all the circumstances was implied because it was obvious, alternatively to give business efficacy to the Services Agreement.

- Thus, the first stage is to identify the source of the express entitlement to a bonus for any project not caught by the set rates identified in the August 2014 email. The Claimant does not point to any words in the August 2014 email which support the express term pleaded at paragraph 12(6) of the Particulars of Claim, other than an implication from the reference itself to, 'base salary'. The use of the phrase is entirely consistent with the fact that there was a specified bonus regime, which as described above, was generally superseded or varied in subsequent years. It does not convey an express entitlement to any other sort of bonus than that expressly identified. Put shortly, the August 2014 email said nothing about any bonuses potentially payable for developments over 5MW in size or outside the 1.3ROC scheme. The Services Agreement did not, therefore, contain any other express entitlement to be paid a bonus other than at the specific rates in respect of the projects to which they applied which, I have found, did not apply to the Cleve Hill Project.

- In its pleaded claim, the Claimant does not rely upon other, later, correspondence to give rise to the incorporation into the Services Agreement of any express term to an entitlement to a bonus as particularised at paragraph 12(6) of the Particulars of Claim. It is obviously not for the Court, absent a pleaded case, to pick through the correspondence and seek to identify from where or how such an express obligation might arise. Even if such a case had been pleaded in general terms, it would not have succeeded. Whilst there were various references at various times in the emails which dealt with Mr McCarthy's remuneration to Mr Hogan seeking to provide 'value' or an 'upside' (which he repeatedly said needed to be agreed by the German directors), there was no unequivocal, express statement that Mr McCarthy was entitled to 'a reasonable bonus' on Cleve Hill in addition to his increasing monthly retainer. Indeed, some statements are inconsistent with such an express entitlement: for example, it is suggested in 2019 that any such 'upside' may require Mr McCarthy to take on board some 'risk'; at other times, additional remuneration through IPO equity was floated as a possible option. Whilst Mr McCarthy was, of course, in fact offered a bonus, of £257,000, he refused this, holding out for more. Its payment did not become obligatory, and the fact of the offer is not of itself directly relevant to determining whether an express obligation to have paid such a bonus existed.

- The primary alternative claim as pleaded therefore fails.

New Alternative Contractual Basis of Entitlement: Implied Term as to a Reasonable Bonus

- In the Particulars of Claim, no entitlement is advanced on the basis of an implied term. The two alternatives, as set out above, were an express entitlement to £7000/MW on achievement of planning; or an express entitlement to a bonus (the amount of which would, implicitly, be reasonable).

- During the course of the Defendant's written opening, Ms Box relied upon the January 2018 email and the April 2019 emails to found what she called the 'January 2018 Agreement' and 'the April 2019 Agreement'. The Defendant's pleaded case had not advanced the existence of these agreements (although it had done clearly in respect of the 2015 and 2016 email exchanges). Instead its original pleaded case relied upon the draft, unsigned (by Mr McCarthy) Consultancy Agreement as having regulated the parties' relationship from 2019, and did not advance an alternative analysis if that was not the case. Given that the Claimant's case on an express term has effectively been resolved against it by considering the meaning and effect of the August 2014 email, and the 2015 and 2016 emails either superseding or amending the terms of the agreement reached in 2014, arguably it was unnecessary for the Defendant to advance a case about what in fact governed the arrangement at the time the bonus was claimed. Nevertheless, it did advance a case as to agreements reached in 2018 and 2019 in its written opening submissions which had not been pleaded. Following an indication of the Court's view as to what was or was not within the Defendant's pleading as regards the case as opened, Ms Box produced overnight a draft Amended Defence. Whilst this was initially objected to, following Mr McCarthy's release from the witness box, instructions were taken and the amendment was consented to by the Claimant. In reality, and irrespective of the concession, the Amended Defence caused no prejudice as the substance of the 2018 and 2019 email exchanges formed part of the overall factual matrix being dealt with. Together with the application to amend, the Defendants provided a draft Order which provided for an Amended Reply to be served on 7 February 2025, after the then anticipated close of the evidence. I queried whether an Amended Reply was necessary. Mr Khan said that, whilst he would take instructions, he did not consider it likely that they would put an Amended Reply in. When he confirmed, having taken instructions, the following morning that the Defendant's application was no longer contested, there was no change in Mr Khan's position as to the need for an Amended Reply, and none was anticipated. There was certainly no suggestion that the consent was conditional on being able to provide such a document (had it been, this would have obviously provoked a discussion about content and timing).

- In closing her case, Ms Box emphasised that if she was correct that the 2014 Services Agreement did not contain the terms sought and/or was superseded that was, on the pleadings, the end of Assensus' case. There was no alternative case arising out of the later agreements alleged to exist by the Defendant. As a matter of analysis, as I have said, that submission was well founded.

- Initially, Mr Khan indicated he was content to remain within his pleaded case. However, after taking instructions over the short adjournment, and no doubt realising the potential implications of Ms Box's submission, Mr Khan then indicated, in response to this, in his oral reply closing submissions, that he intended to submit an Amended Reply.

- A procedure was then directed by which a draft of the Amended Reply would be submitted, allowing the Defendant to consent or object, providing its reasons. By way of draft Amended Reply, Mr Khan produced a document which pleaded:

(1) at paragraph 23(4), that the January 2018 email did not create a superseding agreement, but merely varied the base salary and was consistent with the continuing entitlement to a bonus on Cleve Hill.

(2) what it contends to be various 'offers' by reference to correspondence (referred to above) dated 23 February 2019, 7 May 2020, 27 May 2020 and 24 July 2020.

(3) that as a result of Assensus' efforts over 3.5 years, a DCO was achieved, leading to the successful sale of Cleve Park.

(4) at paragraph 23(7), that the purported January 2018 agreement was unenforceable for want of an intention to create legal relations distinct from the Services Agreement.

(5) in the alternative, at paragraph 23(8), an implied term within the 2018 Agreement that the Defendant would pay the Claimant a reasonable bonus (a) by reason of the course of dealings; (b) because of business efficacy; and/or (c) because it was obvious. The non-payment of a reasonable bonus is then pleaded as a breach of the implied term. Assensus does not suggest that the 2018 Agreement contained an express term in relation to an entitlement to a reasonable bonus in respect of Cleve Hill. Nor does it suggest that the same implied terms existed in the 2015 or 2016 Agreements pleaded by the Defendant.

(6) a materially similar analysis in relation to the April 2019 email and alleged resulting agreement;

(7) an additional plea that the April 2019 email established a mutual understanding between the Claimant and Defendant that the Claimant would be paid a reasonable bonus, which regulated their subsequent work such that it would be unjust or unconscionable for the Defendant to resile from the above understanding with the effect that the Defendant is estopped from doing so.

- The Defendant objected to the amendment. Ms Box argued that the amendments did not have a real prospect of success, both as a matter of law and in light of the evidence already heard, but she accepted that these points could be dealt with by way of further written submissions. However, Ms Box also contended that notwithstanding the ability to make these submissions, if these amendments were permitted, the real prejudice to the Defendant was that fairness required further oral evidence from Mr McCarthy. Ms Box argued that the new estoppel claim raised factual issues as to the parties' alleged mutual understanding and as to the Claimant's alleged regulation of its subsequent dealings with the Defendant and/or reliance on which the Defendant ought to be permitted to cross-examine Mr McCarthy, and that the same was true of the new alleged implied terms. She pointed out that the 2018 and 2019 agreements (such as they were) were partly written and partly oral (and/or partly based on the parties' conduct) and both had been dealt with relatively briefly in cross-examination. She argued that, given the way the case is now put, the Defendant would have further questions to put to Mr McCarthy as to the full scope and nature of those oral discussions and that conduct. That was especially so in circumstances where Assensus relied on an unparticularised course of dealing in support of the implied terms. Ms Box relied upon the judgment of Stewart J in Kimathi v Foreign and Commonwealth Office [2017] EWHC 2145 (QB) that amendments requiring a witness to be recalled are 'very likely to be disallowed'. Ms Box pointed out that the Claimant has known since the date of the Defence that the Defendant's case was that the 2014 Services Agreement had been superseded and that it could have argued at any point that there was an implied term that the Defendant would pay a reasonable bonus in any subsequent agreement at any point after receipt of that Defence.