B e f o r e :

THE HONOURABLE MRS JUSTICE JENNIFER EADY DBE

____________________

Between:

| |

PROSPECT

|

Claimant

|

| |

- and –

|

|

| |

ANDREW EVANS

|

Defendant

|

____________________

David Lemer (instructed by Pattinson & Brewer LLP) for the Claimant

Andrew Evans, the Defendant, in person

Hearing date: 20 February 2025

____________________

HTML VERSION OF JUDGMENT APPROVED

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

This judgment was handed down remotely at 10.30am on 10 March 2025 by circulation to the parties or their representatives by e-mail and by release to the National Archives

Mrs Justice Jennifer Eady DBE:

Introduction

- The claimant brings claims for libel and malicious falsehood in relation to statements made by the defendant on the "Go Fund Me" website on or about 3 September 2023 ("the statement"). Those claims are resisted by the defendant.

- By order of 4 October 2024, this matter was set down for a trial of the following preliminary issues: (1) whether a member of a trade union can defame that union as a matter of law (insofar as not already determined by Mrs Justice Steyn in Prospect v Evans [2024] EWHC 1533 (KB)); (2) the natural and ordinary meaning of the statement; (3) whether the statement referenced the claimant; (4) whether the statement was defamatory of the claimant at common law; (5) whether the statement was a statement of fact or opinion; (6) if a statement of opinion, whether the statement indicated, in general or specific terms, the basis of the opinion; and (7) for the purposes of the malicious falsehood claim, (if deemed appropriate to deal with this issue at this stage) whether the claimant's meaning was one that reasonably available to any publishee.

- In addressing these issues in this judgment, I have first considered the question of law identified at (1). Although not put as an application under CPR 3.4(2)(a), given that a finding in the negative would mean the claimant's "case discloses no reasonable grounds for bringing ... the claim", I have understood that, if it was held that a member of a trade union was legally unable to defame that union, the defendant would indeed ask that the defamation claim be struck out. As, however, this first issue was listed for hearing along with the remaining questions identified by the 4 October 2024 order (including the issue of meaning), in accordance with established practice (Tinkler v Ferguson [2019] EWCA Civ 819, paragraph 9), before otherwise reading into the case, I first read the statement, forming (and making a note of) my own impression before knowing what the parties would say.

Background

- The claimant is a trade union which represents professionals and specialist workers across a range of sectors. It funds its operating costs through membership subscriptions.

- In 2017, the claimant merged with Bectu, a trade union representing workers in the creative industries. Bectu has retained its name for the purposes of representing its members' interests but all members of Bectu are full members of the claimant. The defendant was formerly a member of the claimant, affiliated to the Bectu sector.

- I understand that the defendant was suspended from his membership on 23 June 2021 and that, on 19 December 2023, he was expelled from the claimant. I further understand that the defendant has contested these decisions and has brought various complaints against the claimant, both before the Trade Union Certification Officer and the Employment Tribunal.

The statement

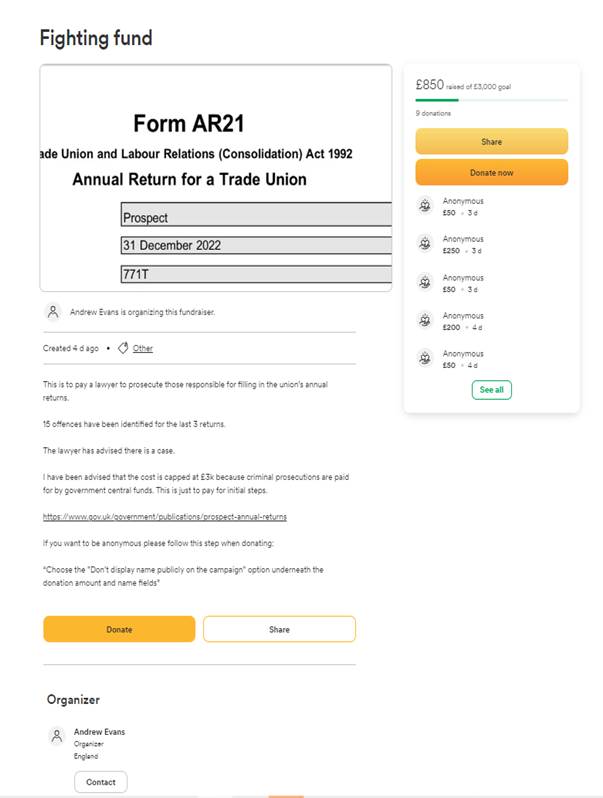

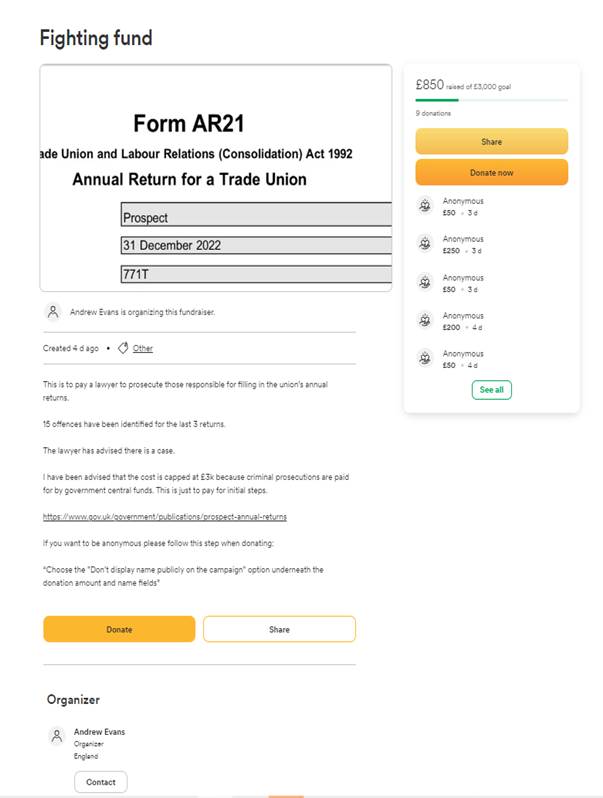

- On 3 September 2023, the defendant made a publication on the website www.gofundme.com ("Go Fund Me"). Go Fund Me is a website where individuals may solicit funds for any purpose, and the defendant made clear he was seeking to raise monies for a "Fighting fund" (that being the title used on his fundraising page).

- The fundraising page in issue is reproduced in its original form at Annex I to this judgment. It contained a screenshot of the claimant's annual return, under which it explained that the defendant was "organizing this fundraiser" and then continued:

"This is to pay a lawyer to prosecute those responsible for filling in the union's annual returns.

15 offences have been identified for the last 3 returns.

The lawyer has advised there is a case.

I have been advised that the cost is capped at £3k because criminal prosecutions are paid for by government central funds. This is just to pay for initial steps."

At this point, the fundraising page provided a hyperlink as follows: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prospect-annual-returns. Clicking on the hyperlink takes the reader to a government webpage on which further links are available to the claimant's annual returns.

The text on the fundraising page then continued:

"If you want to be anonymous please follow this step when donating:

Choose the "Don't display name publicly on the campaign" option underneath the donation amount and name fields."

- The claimant contacted the defendant regarding this fundraising page on 7 September 2023 and correspondence between the parties followed. By email of 12 September 2023, the defendant informed the claimant that he had changed the wording on the page (setting out, within his email, the revised wording). At this stage, I have not been asked to consider the later iteration of the defendant's fundraising page, although it is contained within the papers before me.

Issue (1) – whether a member of a trade union can defame that union as a matter of law

Introduction

- It is convenient to address issue (1) separately to, and in advance of, the remaining questions identified by the 4 October 2024 order. The issue is identified as a pure point of law and is expressly stated to be subject to the question whether this is a matter that has already been determined by Steyn J in Prospect v Evans [2024] EWHC 1533 (KB) ("the Steyn judgment").

- As clarified at the hearing, the claimant does not seek to rely on the Steyn judgment as giving rise to a res judicata estoppel in relation to issue (1), even within the extended Henderson v Henderson sense of that doctrine (Henderson v Henderson (1843) 3 Hare 100). There has, however, been no appeal against the Steyn judgment and both parties accept that I am bound by it. As a starting point, it is therefore necessary to understand what it was that Steyn J decided.

The Steyn judgment

- At an early stage in these proceedings, the defendant applied for a declaration (pursuant to CPR 11) that the court had no jurisdiction to hear the claimant's defamation claim as a trade union can have no standing to pursue a claim in defamation; he subsequently indicated that he also wished to rely on CPR 3.4. The application was listed for hearing before Steyn J on 11 April 2024, and dismissed for the reasons provided in her judgment, handed down on 20 June 2024.

- The defendant's arguments at that earlier hearing are set out at paragraphs 37-41 of the Steyn judgment. In summary: (1) per EETPU v Times Newspapers Ltd [1980] 1 QB 583, the court was prohibited from treating a trade union as a person who can be defamed, and, although EETPU was determined by reference to an earlier statute, the current statute was a pure consolidation Act and was to be given the same meaning; (2) section 10(2) Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 ("the 1992 Act") prohibited the court from treating a trade union as a body corporate except as expressly authorised, which was intended to refer solely to section 12(2) - if section 10(2) were to be construed as applying to any implicit authorisation in Part I of the 1992 Act, the purpose of the prohibition would be undermined; (3) a trade union is a group of people with the right to sue and be sued in its own name, and, as such, it cannot be libelled (Knupffer v London Express Newspaper Ltd [1944] AC 116) - it has no legal personality or reputation distinct from its members (Kelly v Musicians' Union [2020] EWCA Civ 736), and it would be contrary to section 10(2) to treat a trade union as a body corporate or juridical person with a reputation separate from its members; (4) save for partnerships (a pragmatic exception, as a "mere matter of procedure" per Meyer & Co v Faber (No. 2) [1923] 2 Ch 421, at p 441), to have a reputation it was necessary to be an individual or body corporate; (5) alternatively, by analogy with local authorities (per Derbyshire County Council v Times Newspapers Ltd [1992] QB 770 CA), it would be contrary to the public interest for a trade union, as a democratic organisation, to have a right to maintain a claim for defamation.

- Rejecting the contention that the court did not have jurisdiction to determine the claim, Steyn J held that the proper procedural route for challenging the claimant's right to bring a claim in defamation was by CPR 3.4(2)(a), not CPR 11. Going on to find that the claimant was entitled to bring such a claim, Steyn J considered it clear that, by section 10 of the 1992 Act, Parliament had given trade unions sufficient legal personality to be entitled to bring a claim in defamation, explaining:

"49. ... Parliament has conferred on trade unions the right to enter into contracts in its own name (s.10(1)(a)). It is capable of suing in its own name in any cause of action (s.10(1)(b)). It can also be sued in its own name in any cause of action (subject to ss.20-22) or be prosecuted in its own name (s.10(1)(b)-(c)). Plainly, the attributes of a trade union are such that it has a separate reputation, distinct from its members. Although s.10(1) provides expressly that a trade union is not a body corporate, by that provision Parliament has given a trade union sufficient personality to be entitled to bring an action in libel to protect its reputation."

- Asking whether the effect of section 10(2) of the 1992 Act (which provides that a trade union "shall not be treated as if it were a body corporate except to the extent authorised by the provisions of [Part I of the 1992 Act]") was to deprive a trade union of the right it would otherwise have to bring a libel claim, Steyn J was equally clear that it did not: although that provision meant courts could not treat a trade union as a quasi-corporation, the prohibition did not apply to the extent that Parliament had authorised the treatment of a trade union as a quasi-corporation in Part I; that was not limited to section 12(2) of the 1992 Act but encompassed any express or implied authorisation within Part I (thus including those authorisations contained within section 10(1)). That, Steyn J further concluded, reflected a rational judgement on the part of the legislature:

"52. ... It is consonant with the fact that a trade union has a distinct reputation, separate from its members; and it avoids the surprising imbalance to which the defendant's interpretation would lead of an employers' association being able to sue in libel, but not a trade union, and of a union being capable of being sued in libel, while having no right to bring such an action. It is therefore consistent with the interpretative presumption that Parliament is "a rational, reasonable and informed legislature pursuing a clear purpose in a coherent and principled manner": Bennion §11.3."

- To the extent that there might be any doubt as to the meaning of section 10 of the 1992 Act, Steyn J went on, in the alternative, to consider that meaning in the light of the predecessor provisions of the Trade Union and Labour Relations Act 1974 ("the 1974 Act"), with which the court had been concerned in the EETPU case. In this regard, Steyn J considered that changes in wording of the relevant statutory provisions (as between the two Acts), taken together with the removal of a trade union's former immunity from suit in defamation, had removed any doubt as to the meaning of the provision.

- In any event, however, Steyn J took the view that the EETPU case had been wrongly decided, as section 2(1) of the 1974 Act had not deprived trade unions of their established right to bring an action in libel. In reaching this conclusion, Steyn J noted that (as remarked in the leading textbooks) a partnership (which, unless a limited liability partnership, is not in law a person separate from its members) can sue in the firm's name for damage to the reputation of that firm, with the effect that a potentially large and fluctuating group of partners can sue in the name of the firm for defamatory words calculated to injure the firm as a body. Just as a partnership does not need to be treated as a quasi-corporation to be capable of suing in libel, Steyn J considered a prohibition on treating a trade union as a quasi-corporation would not automatically mean it was thereby deprived of the right to bring such a claim:

"58. Given that a trade union (like a partnership) in fact has a reputation distinct from its members, and for decades it had been recognised that it could bring libel proceedings in its own name, I am of the view that the conclusion reached in the EETPU case that Parliament had deprived trade unions of the right to bring such an action was erroneous."

- Steyn J further rejected the defendant's alternative, "public interest", argument, distinguishing trade unions from governmental bodies such as local authorities.

The parties' submissions

The claimant's case

- It is the claimant's case that the question whether a member of a trade union can defame that union as a matter of law was substantively determined as a result of the Steyn judgment, holding that section 10 of the 1992 Act meant that a trade union could be conferred quasi-corporate status to allow it to (amongst other things) sue and be sued in its own name in tort (and, therefore, in defamation) (section 10(1)). As such, there was no reason why a trade union could not sue a member: for these purposes the union and the member were treated as separate entities, with distinct personalities and reputations. The defendant's arguments drawn from the historical case-law were fully considered by Steyn J, but she had ruled that section 10 of the 1992 Act was clear and unambiguous; there was no need to look at older authorities to determine its meaning. As for the objection that any damages due to the trade union would be owed to all members, including a member sued by the union: as "property" of the union it would be vested in trustees, not distributed to all members (section 12(1) 1992 Act).

- Addressing the defendant's arguments as to the treatment of a trade union as analogous to a partnership, the claimant says: (i) this was not the ratio of the Steyn judgment, which held that, for section 10(1) purposes, a union was to be treated as if it were a corporation; (ii) the analogy with partnerships was considered by Steyn J only in the alternative; (iii) in any event, the defendant had cited no authority confirming that a partnership could not sue a partner in libel (and note the (obiter) suggestion to the contrary in Metropolitan Saloon v Hawkins (1859) 4 Hurl.&N 87 at pp 92-93, which was not precluded by section 12 Partnership Act 1890 (which, in any event, had to be read subject to sections 10 and 11 of that Act). As for the argument that it would be legally incoherent if a member who was also an officer of the trade union could be sued by the union in defamation when the union could be vicariously liable, this would still not remove the liability of the member/officer as the primary tortfeasor.

The defendant's position

- Accepting that the Steyn judgment had ruled that a trade union could sue in libel in its registered name, the defendant says that did not determine the separate question whether a union member could defame their union. Similarly, holding that a trade union has a reputation (tied to its name) did not answer the question whether it could be treated as a separate entity from a member alleged to have defamed it: whether or not a trade union had a separate reputation was a secondary question to whether it had separate status from its members (see per Eady J North London Central Mosque v Policy Exchange and anor [2009] EWHC 3311 (QB)). It is the defendant's case that, although a trade union can be treated as a corporate body in that it can sue in its registered name, that could not make it separate from its members or give the court implied authorisation to treat it as separate from its members to all extents: that would be contrary to case-law, which had always distinguished between the position of a trade union vis-à-vis third parties and its position vis-à-vis its own members (Taff Vale v The Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants [1901] UKHL 1; Kelly v National Society of Operative Printers' Assistants (1915) 84 LJKB; Bonsor v Musicians' Union [1954] Ch 479 CA; Bonsor v Musicians' Union [1956] AC 104; Kelly v Musicians' Union); it would also render section 10(2) of the 1992 Act redundant. The defendant thus submits that, not being separate from its members, a trade union cannot sue a member except as authorised in statute or for breach of contract; otherwise the union would be suing itself.

- The defendant further contends that section 10 of the 1992 Act has the effect that a trade union is treated in many ways as analogous to a partnership. That a partnership can be sued by the name of the firm is "merely a convenient method of expressing the names of those who constituted the firm when the cause of action accrued" (see Lindley & Banks on Partnerships 21st ed. para 14-08); the same was the position with a union (Taff Vale; Yorkshire Miners' Association v Howden [1905] UKHL 868). A partner could not defame their partnership because they would be defaming themselves: where a partnership sought to sue in defamation, the partners (as a group) would have to show joint damage (Lindley para 14-60); that would not be the case if one of the partners had defamed the firm. The same, by analogy was true of a trade union: it would need to show joint damage to all its members, and compensation would need to be quantified and assessed for each member of the union (including the member sued) at the time the action accrued - an impossibility where a member has made the statement in issue. Moreover, a partnership could not sue a partner for libel because all would be jointly and severally liable (section 12 Partnership Act 1890); similarly, a union in some cases would be liable for acts and statements made by its members (who could also be officers of the union), meaning it would be liable to damages from itself, which was legally incoherent.

Issue (1) – discussion; decision

- It is unclear to me why issue (1) was not expressly raised as a question to be determined at the hearing on 11 April 2024; certainly, much of the argument before me would seem to have been a further iteration of the points raised at that earlier stage. In any event, however, I am satisfied that the Steyn judgment provides a complete answer to the point as now identified, making it clear that, as a matter of law, a member of a trade union can defame that union.

- In reaching this conclusion, I of course recognise that a trade union will typically be an unincorporated association of its members. As the authors of Harvey on Industrial Relations and Employment Law observe (see paragraph M [151]:

"In law a trade union is typically an unincorporated association. It is, in theory, simply a number of individual trade unionists described by a convenient label: the union is 'they', not 'it'."

- That position is acknowledged by the 1992 Act, both in the definition of a trade union provided by section 1, and by the express recognition at section 10(1), that "a trade union is not a body corporate". Notwithstanding that clear statement of what a trade union is not, however, section 10(1) then continues with the following caveat:

" ... but –

(a) it is capable of making contracts;

(b) it is capable of suing and being sued in its own name, whether in proceedings relating to property or founded on contract or tort or any other cause of action; and

(c) proceedings for an offence alleged to have been committed by or on its behalf may be brought against it in its own name."

And by section 10(2) it is provided:

"A trade union shall not be treated as if it were a body corporate except to the extent authorised by the provisions of this Part."

- In reaching her decision, Steyn J considered that the meaning of section 10 was clear and unambiguous: by section 10(1), Parliament had given trade unions sufficient legal personality to sue and be sued, including in tort (and, therefore, in defamation); although, by section 10(2), there was a prohibition on treating a trade union as a body corporate, that expressly did not apply to the extent that Parliament had otherwise allowed under Part I of the 1992 Act; as Parliament had allowed that trade unions should be treated as if they were quasi-corporations for the purposes expressly provided by section 10(1), the prohibition provided by section 10(2) did not bite in those respects. While acknowledging that headings are to be given less weight than the specific language of the section, Steyn J considered that the heading to section 10 – "Quasi-corporate status of trade unions" – accurately reflected the position then set out.

- In holding that a trade union had a "separate reputation, distinct from its members" (Steyn judgment paragraphs 49, 52, and 58) Steyn J was thus clearly not failing to engage with the primary question (per North London Mosque v Policy Exchange) whether the union had a separate legal status from its members; as her ruling makes clear, by section 10(1) of the 1992 Act, Parliament has expressly conferred such a separate status – akin to that of a corporate body ("quasi-corporate status") – upon trade unions for the purposes provided, which include the ability to sue in tort (section 10(1)(b)). Moreover, in so ruling, Steyn J was plainly alive to the earlier case-law and legislative interventions, which provide the legal narrative to the history of trade unionism in this jurisdiction (see the Steyn judgment at paragraphs 19-35). Having considered this jurisprudential context, however, Steyn J was clear that her starting point must be section 10 of the 1992 Act. Adopting that approach, Steyn J determined that a trade union acting in its own name (that is, as an "it" not a "they" in this context) was to be treated as having sufficient personality as a quasi-corporation to bring an action in libel to protect its reputation.

- The defendant's submissions on issue (1) essentially replicate the arguments rejected by the Steyn judgment. Having not sought to challenge that decision on appeal, it is, however, not open to the defendant to seek to go behind the implications of Steyn J's ruling by re-phrasing the question she has already answered. The Steyn judgment did not fail to engage with the general proposition that a trade union is a union of members, but concluded that Parliament had legislated to confer a separate status on trade unions such that they can sue in tort in their own name. As such, as provided by section 10 of the 1992 Act, a trade union is treated as being a separate legal entity from its members and can thus pursue a claim of defamation in its own right. Given that distinction – as explained in clear terms by the Steyn judgment – there can be no prohibition upon a trade union suing one of its members for defamation: a trade union possesses a reputation distinct from that of its membership, and, in seeking to protect that reputation, section 10(1)(b) of the 1992 Act expressly provides that it is capable of suing in its own name, thus conferring upon the union a quasi-corporate status that is not precluded by section 10(2) (Steyn judgment, paragraph 50).

- It is unnecessary to address the defendant's arguments relating to partnerships. Although the Steyn judgment drew an analogy between the trade unions and partnerships when addressing the question whether an unincorporated union or firm could possess a reputation distinct from its members, that was not the ratio of the decision, which has to be viewed through the particular statutory scheme that Parliament has put in place for trade unions. Save for recognising that both trade unions and traditional partnerships can provide examples of how an unincorporated association might have its own distinct reputation (separate from that of its members), I do not consider it is helpful to seek to draw further comparisons or analogies between these different entities.

- Turning then to the defendant's contention that any damages paid to the union would need to be distributed to the membership, which might include the tortfeasor (assuming they remained a member), I cannot see that this gives rise to any sensible objection. By virtue of section 12(1) of the 1992 Act, property belonging to a trade union (which would include damages awarded by a court) has to be vested in trustees in trust for the union. While the ultimate beneficiaries of the trust will be the union membership (which, in this scenario, may include the tortfeasor), that does not imply that the damages will simply stand to be distributed in the way the defendant has suggested. I am similarly unpersuaded by the defendant's argument that a trade union's own potential vicarious liability (assuming the tortfeasor is both a member and an officer of the union) means it would be legally incoherent for it to be able to sue a member in defamation. Even if it were to be assumed that the trade union could be vicariously liable for the tort in this scenario (and I confess to finding it difficult to envisage the circumstances in which this might arise), that would not detract from the primary liability of the member/officer for the wrong done to the union.

- For the reasons provided, my decision in relation to issue (1) is that, as already determined by the Steyn judgment, as a matter of law, a member of a trade union can defame that union.

Issues (2)-(6)

- I turn next to issues (2)-(6), which relate to the defamation claim and the defendant's defence of honest belief.

The legal framework

Approach

- Reflecting the separate questions identified in the order of 4 October 2024, I have below set out the relevant legal principles under sub-headings which correspond to preliminary issues (2)-(6). I bear in mind, however, the risk of adopting an overly linear or compartmentalised approach; see per Warby J (as he then was) at paragraphs 16-17 Triplark Ltd v Northwood Hall [2019] EWHC 3494 (QB); Warby LJ at paragraph 23 Blake v Fox [2023] EWCA Civ 1000; [2024] EMLR 2; and Collins Rice J at paragraph 17 Bridgen v Hancock [2024] EWHC (KB)1603. I accept that the questions to which these issues give rise can be inter-related, and I have approached my task accordingly.

Natural and ordinary meaning (issue (2))

- The principles governing the determination of meaning are well-established. Acknowledging a degree of artificiality in the process - given that different people may interpret what they read in different ways - the court's task is "to determine the single natural and ordinary meaning of the words complained of, which is the meaning that the hypothetical reasonable reader would understand the words bear"; per Nicklin J, Koutsogiannis v Random House Group Ltd [2019] EWHC 48 (QB), [2020] 4 WLR 25, paragraph 11. The relevant principles are summarised by Nicklin J at paragraph 12 Koutsogiannis; I have kept these in mind in reaching my determination.

- At paragraph 13 Koutsogiannis, Nicklin J addressed the Chase levels of meanings (per Chase v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2002] EWCA Civ 1772, [2003] EMLR 11 at paragraph 45), noting (per Brown v Bower [2017] EWHC 2637 (QB); [2017] 4 WLR 197) that these broadly identify three types of defamatory allegation: (1) the claimant is guilty of the act; (2) there are reasonable grounds to suspect that the claimant is guilty of the act; and (3) there are grounds to investigate whether the claimant has committed the act.

Reference (issue (3))

- At paragraph 15, Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2015] EWHC 2242 (QB) Warby J (as he then was) addressed the issue of reference, setting out the following principles (I paraphrase): (1) the words complained of should be published "of the claimant", albeit that does not mean the claimant must be named - the question is whether reasonable people, acquainted with the claimant, would understand the words to refer to them; and (2) the test is objective, there is no need to identify such people.

- In the present case, an issue arises as to whether the reasonable reader would understand the words in issue to refer to the claimant or to its officials or employees. In this regard, it is common ground that the position can be seen as analogous to companies and their officers, the case-law in relation to which was helpfully reviewed by Tipples J in Public Joint Stock Company Rosneft Oil Company v HarperCollins Publishers Limited [2021] EWHC 3141 (QB). Drawing on the principles thus identified in Rosneft, it is clear that, if a trade union is bringing an action in defamation in its own name, then it cannot do so in respect of allegations which reflect solely on its individual officers; where the words might be thought to "reflect primarily upon human beings" the court will examine carefully a contention that they are damaging to the union's reputation (Rosneft, paragraph 22). That said, allegations about union officials (or employees, if they relate to their work in their employment) will often reflect on the trade union, either because those acts will be identified with the union, or because the allegations involve some imputation against the methods of selection of officials (or staff), or their supervision, or because allegations against a trade will often involve, by necessary inference, imputations against those who are responsible for its direction and control (Rosneft, paragraph 16). Accepting that an allegation might defame both a trade union and its officers, the task is to identify whether the union itself is implicated; if not, then it will only be the individual that is defamed, not the union (Rosneft, paragraphs 20-21). The test can be seen as twofold: (1) do the words used refer to the union?; (2) do those words convey a defamatory meaning about the union? (Rosneft, paragraph 22).

Defamatory at common law (issue (4))

- In Millett v Corbyn [2021] EWCA Civ 567, Warby LJ explained that a meaning will be defamatory at common law (and therefore actionable) if it satisfies two requirements:

"9. ... The first, known as "the consensus requirement", is that the meaning must be one that "tends to lower the claimant in the estimation of right-thinking people generally." The Judge has to determine "whether the behaviour or views that the o?ending statement attributes to a claimant are contrary to common, shared values of our society...." The second requirement is known as the "threshold of seriousness". To be defamatory, the imputation must be one that would tend to have a "substantially adverse e?ect" on the way that people would treat the claimant...."

- Considering this question in relation to the Chase levels of meaning, in Clarke v Guardian News [2023] EWHC 2734, Jeremy Johnson J observed as follows:

"19. ... All Chase levels (and all intermediate levels between Chase 1 and Chase 3) may be defamatory of the claimant, but the potency of the defamatory sting decreases from level 1 to level 2 to level 3."

Fact or opinion (issue (5))

- By section 3 Defamation Act 2013 ("the 2013 Act") it is provided that a defence of honest opinion will be established where three conditions are met; the first of those conditions engages the question identified by issue (5), namely: "(2) ... that the statement complained of was a statement of opinion."

- As the statute thus makes clear, it is not the meaning of the statement that is in issue, but the words used, albeit the answer to the question posed will depend on how those words would be understood by the ordinary reasonable reader. The principles drawn from the case-law that will inform the court's approach to determining whether a statement is one of fact or opinion were summarised by Nicklin J at paragraph 16 Koutsogiannis, as follows:

"i) The statement must be recognisable as comment, as distinct from an imputation of fact.

ii) Opinion is something which is or can reasonably be inferred to be a deduction, inference, conclusion, criticism, remark, observation, etc.

iii) The ultimate question is how the word would strike the ordinary reasonable reader. The subject matter and context of the words may be an important indicator of whether they are fact or opinion.

iv) Some statements which are, by their nature and appearance opinion, are nevertheless treated as statements of fact where, for instance, the opinion implies that a claimant has done something but does not indicate what that something is, i.e. the statement is a bare comment.

v) Whether an allegation that someone has acted "dishonestly" or "criminally" is an allegation of fact or expression of opinion will very much depend upon context. There is no fixed rule that a statement that someone has been dishonest must be treated as an allegation of fact."

Indication of basis (issue (6))

- Issue (6) arises from the second of the three conditions necessary for the defence of honest opinion provided by section 3 of the 2013 Act, which requires: "(3) ... that the statement complained of indicated, whether in general or specific terms, the basis of the opinion." As Warby J observed in Triplark, there is a degree of overlap between this condition and the question whether a statement is one of opinion:

"17.... Although an inference may amount to a statement of opinion, the bare statement of an inference, without reference to the facts on which it is based, may well appear as a statement of fact ..., not every inference counts as an opinion; context is all. Put simply, the more clearly a statement indicates that it is based on some extraneous material, the more likely it is to strike the reader as an expression of opinion."

The parties' positions

The claimant's case

- For the claimant it is said that ordinary and natural meaning of the statement (issue (2)) is that:

"The Claimant had, through its officers, commissioned at least 15 criminal offences in the preparation and filing of annual returns which were deliberately false. The Claimant was responsible for permitting those officers to commission those offences. The Claimant's criminal activity was longstanding and systemic." (paragraph 5 Particulars of Claim)

This, the claimant submits, is a Chase level 1 meaning.

- The claimant further contends that the words complained of constitute a statement of fact, not opinion (issue (5)), albeit, if understood to be an expression of opinion, the claimant would accept that the statement sets out, in general terms, the basis for that opinion (issue (6)), namely the content of the claimant's annual returns and/or the receipt of advice from a lawyer. The claimant further contends that there can be no doubt that the reasonable reader would understand that it was referenced by the statement (issue (3)), which is about the claimant and its annual returns. It says the statement was defamatory of the claimant at common law (issue (4)), which would be so even if the Court were to conclude that the words used did not have the Chase level 1 meaning the claimant asserts.

The defendant's position

- The defendant says, however, that the ordinary and natural meaning of the statement (issue (2)) is as follows:

"That an objective, impartial and reasonable jury or bench of magistrates or judge hearing a case alone, properly directed and acting in accordance with the law, is more likely than not to convict those people responsible for filling in the Claimant's annual returns for up to 15 offences and that prosecuting those people would be in the public interest.

That these offences relate to the annual returns from the last 3 years.

That the Defendant contacted a lawyer who advised there is a case and that the costs of any prosecution would be capped at £3000 because they are recoverable from central funds."

- The defendant submits that the underlined passages are statements of fact; the remainder a statement of honest opinion (issue (5)). To the extent that the statement amounted to an expression of honest opinion, the defendant says the basis for this opinion was indicated in general terms as being the 15 offences identified relating to the annual returns of the union, with a link to the annual returns being provided (issue (6)). As for whether the statement referred to the claimant (issue (3)), the defendant points to the reference to the aim of prosecuting "those responsible for filling in the union's annual returns"; he contends that, as the statement plainly referred to people, it was not directed at the claimant and no reasonable person could think that it was. Equally, although accepting that stating "the officers should be prosecuted" would be defamatory of "the officers" at common law ("being Chase level 2"), the defendant says it cannot be defamatory of the claimant (issue (4)).

Issues (2)-(6) – discussion; decisions

- The statement in issue in this claim appears on a crowd-funding platform, under the heading "Fighting fund". The reader naturally then looks down the page to see what the fundraiser is for. The screenshot of the claimant's annual return for 2022 does not, of itself, explain anything, but it does draw attention to the fact that this concerns the claimant. Below the screenshot, information is then provided as to who is organising the fighting fund (the defendant), and why funds are being sought. My first impression when reading the script below the screenshot was that this told me that the defendant considered there were reasonable grounds to think that the claimant trade union was guilty of 15 criminal offences relating to the contents of its annual returns over the past three years, that a lawyer had advised him that there was a case to answer, and that the funds raised would be used to take the initial steps necessary for a prosecution.

- The defendant resists, however, the suggestion that the statement referred to the claimant. He points to the fact that the prosecution was to be of "those responsible for filling in the union's annual returns"; he says that any reasonable reader would have understood this to refer to individual union officials, not the union itself: thus the statement neither referred to, nor defamed, the claimant. And that, the defendant says, was well understood by those acting for the claimant in the initial communications of September 2023, who then also wrote on behalf of the claimant's General Secretary, President, and Director of Finance and Estate Management. The defendant further contends that saying someone should be prosecuted expresses an opinion; in this case, the basis for that opinion was provided by looking at the annual returns (a link to which was included as part of the statement). He points out that the Code for Private Prosecutors (issued by the Private Prosecutors' Association) makes clear it would be for the prosecuting solicitor (and counsel) to be satisfied that there was a prima facie case, supported by evidence; and advises that it would be unwise to bring a private prosecution unless the "Full Code Test" was met as, if it were not, the Crown Prosecution Service would be likely to take over the prosecution and discontinue the case. The "Full Code Test" is the two-fold test ((i) the evidential test; (ii) the public interest test) under the Code for Crown Prosecutors. The defendant says that identifying a case that is to be prosecuted is thus an expression of a view of the evidence, it is not an attribution of guilt (see Glinski v McIver [1962] AC 726 per Lord Denning at p 758).

- Addressing first the question of reference (issue (3)), I acknowledge that the opening sentence of the statement indeed refers to "those responsible for filling in the unions annual returns". I had not overlooked that sentence, but had understood it to be an acknowledgement of the fact that the claimant would necessarily have to act through its individual officers and employees; it did not remove from my mind the force of the more general allegation that the defendant considered there were reasonable grounds to think that the claimant had been guilty of criminal conduct. Certainly, in reading the statement, the screenshot at the top of the page had focussed my attention on the claimant, and I was made alive to the fact that the annual return was a statutory requirement for a trade union by the reference to the 1992 Act in that screenshot (a point also reinforced by clicking on the hyperlink, which takes the reader to the gov.uk website page containing the claimant's annual returns "as submitted to the Certification Office"). Set in that context, when reading that "15 offences have been identified for the last 3 returns", I understood that was referring to offences for which the claimant would be responsible. Reading the statement as a whole, I understood that it expressly referred to the claimant and conveyed the implication that the claimant would itself be responsible for any criminal conduct identified (thus satisfying the requirements identified in Rosneft).

- Reflecting on the submissions made to me by the defendant, addressing the issue of reference, I can see that it might be possible to analyse the statement in such a way as to also suggest liability on the part of individual officers or employees of the claimant, which would no doubt explain why those acting for the claimant initially also raised concerns about the allegations vis-à-vis specific officials. Allowing for this further interpretation of the statement does not, however, cause me to consider that I should revisit my initial understanding regarding its reference to the claimant. Although referring to "those responsible", in contrast to the clear identification of the claimant, the statement does not seek to inform the reader of the identities (or even the roles) of any individual officers or employees. Similarly, although there is a clear link made to the claimant's legal responsibility for the annual returns in issue, nothing is said that would link a particular individual to some criminal wrong-doing in this regard, or would suggest that they would do other than stand for the claimant (that is, as representing the claimant) in any criminal prosecution. In any event, even if a reader did pick up on this alternative interpretation, I do not see that that would detract from the force of the allegation made against the claimant itself.

- Before specifically answering the question whether the statement was defamatory of the claimant at common law (issue (4)), I first return to the question of meaning (issue (2)). I think it is fair to say that the meaning I gave to the statement when first reading it falls somewhat closer to the position adopted by the defendant, although I did not (and would not) use the same words. More particularly, I would agree with the defendant that the import of the words used is at a Chase 2, rather than (as the claimant has urged) a Chase 1, level.

- For the claimant it is contended that the meaning posited by the defendant is overly strained: the ordinary reader would not read the statement with the provisions of the Code for Private Prosecutors, or the CPS "Full Code Test" in mind. Moreover, in saying "15 offences have been identified for the last 3 returns", the claimant says the defendant was asserting, as a matter of fact and without equivocation, that criminal offences had been identified, and this criminality was extensive: there was no suggestion that there were merely reasonable grounds to suspect (or investigate) whether such offences had been committed, and credence was added by the reference to legal advice. For my part, however, while I did not think that the ordinary reader would have in mind prosecutorial Codes (whether those of private prosecutors or the CPS), the overall impression I obtained was that the defendant was saying he believed there were reasonable grounds for thinking criminal offences had been committed, not that guilt had been established. That, it seemed to me, was the implication of the lawyer's advice that "there is a case"; it was also how I interpreted the intention to pursue a prosecution. Having reflected on the claimant's submissions, I remain of this view. Without undertaking an overly pernickety approach, I consider the ordinary reasonable reader would understand the defendant was saying that, based on the legal advice he had received, he believed there were reasonable grounds for thinking the claimant was guilty of criminal offences in relation to its annual returns, such that a prosecution could properly be pursued.

- Returning to the question posed at issue (4), however, I am satisfied that, in referring to the defendant's belief that there were reasonable grounds to suspect the claimant of criminal wrongdoing (as I find the statement does), it is plain that the words used are defamatory of the claimant at common law. As the Steyn judgment expressly acknowledged, the claimant trade union has a reputation that is distinct from its membership. While the statement is to be characterised as Chase level 2, that does not mean it is not defamatory (Clarke v Guardian News). To say that, having been advised by a lawyer, the defendant considered there were reasonable grounds for suspecting the claimant had committed criminal offences in its completion of its annual returns is self-evidently an allegation that would tend to lower the claimant in the estimation of right-thinking people, and would be likely to have a substantially adverse effect on how people would treat it (whether they be (potential) members of the claimant or third parties).

- The questions identified at issues (5) and (6) are interrelated to that of meaning. Although, to better explain my conclusions, I have set out my reasoning on these issues separately, these are questions that I have considered together and in parallel.

- Returning then to my initial impression of what was being said, I have reminded myself that opinion is something "which is or can reasonably be inferred to be a deduction, inference, conclusion, criticism, judgment, remark or observation" (Koutsogiannis paragraph 16 ii)). Although I must focus on the words used by the defendant, the question for me is how those words would strike the ordinary reasonable reader, allowing that context may be an important indicator of whether they are fact or opinion (Koutsogiannis paragraph 16 iii)). Adopting this approach, and allowing that, taken by itself, the sentence "15 offences have been identified for the last 3 returns", might seem to be a bald statement of fact, I consider the ordinary, reasonable reader would see that in the context of the information being provided taken as a whole. The text provided on this fundraising page is short, and would naturally be read holistically. Having referred to the identification of offences, it is significant that the next sentence states (as a fact) "The lawyer has advised there is a case", and a link is provided to the relevant returns. Viewing the words used in context (as I am satisfied the ordinary, reasonable reader would), the objective conclusion would be that the defendant is expressing his opinion – his deduction, inference, conclusion, or judgement – based on the annual returns and the legal advice he has received. I do not consider that the ordinary reader would (as the defendant has suggested) undertake their own analysis of the annual returns, but it is not fatal to the requirement under section 3 of the 2013 Act, which allows that the basis of the opinion may be indicated in general terms. That, I find, is the position here.

- In determining issues (2)-(6), I therefore find:

Issue (2): the natural and ordinary meaning of the statement is as follows:

There are reasonable grounds for thinking that the claimant trade union is guilty of criminal offences relating to the contents of its annual returns over the past three years.

A lawyer has advised that there is a case to answer.

The funds raised (from this fundraiser) will be used to take the initial steps necessary for a prosecution.

Issues (3) and (4): the statement referred to the claimant and conveyed a defamatory meaning about the claimant; the statement was defamatory of the claimant at common law.

Issues (5) and (6): to the extent underlined, the statement was an expression of opinion; otherwise it was a statement of fact. The basis for the opinion was indicated in general terms to be the content of the defendant's annual returns together with the legal advice received.

Issue (7)

- The final issue relates to the claimant's claim of malicious falsehood, asking (if deemed appropriate to deal with this issue at this stage) whether the claimant's meaning was one that was reasonably available to any publishee.

The legal framework

- The approach to meaning in malicious falsehood claims is different to that adopted in defamation as there is no single meaning rule (Ajinomoto Sweeteners Europe SAS v Asda Stores Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 609). My answer to the question posed by (2) is, therefore, not determinative to the separate question identified at issue (7). As Longmore LJ observed in Tinkler v Ferguson [2019] EWCA Civ 819:

"29. ... for the purposes of the tort of malicious falsehood; a claimant will be entitled to succeed if he can show that a substantial number of people would have reasonably read the Announcement in a way that accords with his preferred meaning. In other words, a claimant can seek to show that any reasonably available meaning of the statement in question was false and made maliciously."

- Accepting that those reading a statement may afford it different meanings, where the publication has been to a large, but unquantifiable, number of people, it is likely to be impossible to ascertain what meaning/s each reader has attributed to the statement. In such circumstances, a claim of malicious falsehood can be maintained provided the claimant can establish that the meaning/s it contends would have been understood by a substantial number of those reading the statement (Peck v Williams Trade Supplies Limited [2020] EWHC 966 (QB), per Nicklin J paragraph 16; Tinkler v Ferguson and ors [2019] EWCA Civ 819, per Longmore LJ paragraph 29). Where, however, the publication has been to only one person, or to a few people (so, where those reading the statement can be ascertained), the question becomes: what meaning was attributed to the statement by the person/people concerned? (see per Tugendhat J paragraph 31 Ajinomoto Sweeteners Europe SAS v Asda Stores Ltd [2010] QB 204 (albeit the final decision in that case was set aside on appeal, see [2010] EWCA Civ 609), and the observations of Nicklin J at paragraphs 16-18 Peck).

The parties' positions

- For the claimant it is noted that, while the defendant's publication was available to the world at large, the question was whether the meaning given to the statement was likely to cause financial loss to the claimant. In the circumstances of this case, the claimant accepts that the relevant class of publishees was likely to be limited, and ought to be identifiable, such that, in determining meaning, it would be relevant for the court to hear evidence as to how the relevant publishees understood the publication. Although the claimant had identified the responses of three publishees in its particulars of claim, as yet the defendant had not provided a list of those he had notified or informed about the fundraiser. Given the absence of evidence from specific publishees, the claimant did not consider this was an issue that could be appropriately determined at this preliminary stage. In the alternative, the claimant submits that its contended meaning was one that was reasonably available, and the court should so find (even if the court did not accept the claimant's contended meaning for the purposes of the defamation claim, that would not preclude a conclusion that that meaning was a reasonably available one).

- The defendant, on the other hand, pointed out that the claimant's most recent response to a request under CPR 18 had stated that it was still unable to clarify whether reliance was being placed on the alleged harm done to its reputation in respect of three people at a meeting or in relation to "the world at large". In these circumstances, it would be appropriate to determine, as a preliminary issue, whether the meaning contended for by the claimant was one that was reasonably available to the world at large.

Issue (7) – discussion; decision

- In Peck, the publication complained of had been to a single, identifiable, individual. Noting that directions had not been given for the filing of evidence, such that the court had no witness statement from the sole publishee, Nicklin J declined to determine the issue of meaning for the purposes of the malicious falsehood claim in that case; as he observed:

"16. ... Ascertaining whether the pleaded meaning is an available meaning will be academic if it is not the meaning that the publishee understood the words complained of to bear. It is that meaning which a claimant must demonstrate to be false, published maliciously, and either to have caused special damage or, where the claimant can and does rely on s. 3 Defamation Act 1952, that it was likely to do so."

- Although the present case is not one in which publication was to a single individual, the circumstances are such that, even if published to the world at large, the damage done to the claimant (or likely to be done) would relate to a far smaller class of publishees. That class is likely to be identifiable, and it is thus likely to be open to the court to determine at trial the actual meaning given to the publication on the evidence of those concerned. Seeking, absent such evidence, to decide this as a preliminary issue at this stage would be premature. In the circumstances, I make no determination on issue (7).

Disposal

- For the reasons provided, it is duly determined that:

Issue (1): as already determined by the Steyn judgment, as a matter of law, a member of a trade union can defame that union.

Issue (2): the natural and ordinary meaning of the statement is as follows:

There are reasonable grounds for thinking that the claimant trade union is guilty of criminal offences relating to the contents of its annual returns over the past three years.

A lawyer has advised that there is a case to answer.

The funds raised (from this fundraiser) will be used to take the initial steps necessary for a prosecution.

Issues (3) and (4): the statement referred to the claimant and conveyed a defamatory meaning about the claimant; the statement was defamatory of the claimant at common law.

Issues (5) and (6): to the extent underlined, the statement was an expression of opinion; otherwise it was a statement of fact. The basis for the opinion was indicated in general terms to be the content of the defendant's annual returns together with the legal advice received.

Issue (7): in respect of the claimant's claim of malicious falsehood, at this stage it is not appropriate to deal with the question whether the meaning for the statement contended by the claimant was one that was reasonably available to any publishee.

- Within 7 days of the date on which this Judgment is handed down, the parties are to lodge an agreed order addressing any consequential matters or, failing agreement, to lodge and exchange their rival draft orders and written submissions as to all disputed consequential matters; should either party seek permission to appeal from this court, they should lodge and serve their grounds of appeal and any submissions in support by the same deadline.

Annex I