DECISION

Introduction and Issues

1. Anyone who has attended a careers fayre will be familiar with the “roller banner stand” (‘RBS’) . One or more erected RBSs usually appears behind the stall where prospective employers sit ready to receive those interested (or otherwise) in what they have to say. The RBS will have a printed graphic or advert upon a banner attached to it. Upon that banner will be an image, for example, information by way of the name and details of a company.

2. But is an RBS at the point of importation in this case furniture (or a part thereof) for customs duty purposes?

3. The Appellants in this case are Quantum House Holdings Limited (‘QHH’). The Respondents are the Commissioners for His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (‘HMRC’).

4. This is an appeal to the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) (‘the Tribunal’) by QHH. There are four grounds of appeal.

5. The principal issue before us is whether, for the purposes of customs classification and therefore the customs duty rate, an RBS at the point of import (without the banner containing the information) is ‘furniture’ (or a part thereof) with 0% duty rate or ‘another article of aluminium (a base cassette and frame) with a 6% duty rate, or something else entirely.

6. Until 30 August 2018 the uniform approach across the EU was to treat such items as furniture. That changed after that date, following the combined nomenclature explanatory note (‘CNEN’) issued by the EU as explained below.

7. The appeal requires the Tribunal to consider the details of the provisions of the European Union’s (‘EU’) Union Customs Code (Council Regulation (EU) No. 952/2013) (‘UCC’), Regulation (EU) 2015/2446 (‘the Delegated Act’), Regulation (EU) 2015/2447 (‘the Implementing Act’), the Combined Nomenclature and its explanatory notes, the explanatory notes to the Nomenclature of the Customs Co-operation Council, otherwise known as Explanatory Notes to the Harmonised System, and other international agreements such as Article X of the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade. There are also significant Court of Justice of the European Union (‘CJEU’) and domestic cases as well as a number of different pieces of guidance issued by HMRC.

8. This issue we shall term ‘the classification ground’.

9. There is also a challenge to HMRC’s reliance upon the CNEN issued by the EU effective from 31 August 2018 which advised that “information stands” were no longer classified under the heading ‘furniture’. As part of this, it is said that HMRC’s change of classification was not sufficiently reasoned. That ground is closely aligned with the principal issue, and we shall deal with it as part of the ‘classification ground’.

10. In the alternative, QHH invite the Tribunal to allow the appeal in part by reference to the point in time that QHH found out from the French authorities that the classification had changed rather than the date the explanatory note to the combined nomenclature was published and HMRC’s change in the classification as a result. The difference is some seven months. This we shall term the ‘timing ground’.

11. Finally, the appeal also requires the Tribunal to decide whether QHH were the proper person to be sent the post clearance demand note (“C18 Notice”) seeking to enforce the customs debt HMRC said had arisen as a result of the classification away from furniture. This, as will be seen, necessarily includes an analysis of estoppel by convention. This we will term ‘the procedural ground’.

12. QHH appeal, by section 16 (1) of the Finance Act 1994, against HMRC’s decision dated 12 October 2020 to issue a C18 Notice made up of £214,751.13 in customs duty and £42,918.04 in VAT. That totals £257,669.17. That decision was upheld by an independent review by HMRC on 2 March 2021.

13. QHH essentially submit:

(a) the RBS is furniture with a duty rate of 0% or,

(b) alternatively, a base metal fitting with a duty rate of 2.7% and in any event,

(c) that HMRC improperly relied upon an explanatory note promulgated by the European Union to change the code from 31 August 2018 when they issued the C18 Notice. Retrospectivity should not be permitted and their decision is invalidated by failing to provide sufficient reasons for the change,

(d) if not furniture, then the change in classification (and therefore duty) should be applied from March 2019 when the Appellant became aware of the change as it would only be at that point that a uniform approach was being taken across the customs territory

(e) QHH were not liable for the customs debt as the customs declaration showing their unique registration identity was put there in error. As a result, the demand from HMRC for unpaid duty was sent to the wrong person, and

(f) they are not estopped by convention from relying upon that.

14. HMRC essentially submit:

(a) the RBS is an aluminium frame and base cassette with a duty rate of 6%,

(b) HMRC properly relied upon the explanatory note in coming to that conclusion,

(c) HMRC’s decision to classify the RBS in that way from the 31 August 2018 cannot be impugned and there is no reason for that classification to begin when QHH found out about the CNEN,

(d) QHH were the declarant on the customs declaration and liable for the customs debt but, if not,

(e) QHH are estopped by convention from appealing to the Tribunal on that basis.

15. We heard the appeal over four days having adjourned to receive written submissions in advance of the final day. The Tribunal was greatly assisted by the oral and written submissions of Mr Grayston, Avv. Rovetta and Ms Thelen in a complex case with a number of moving parts and a lot of material.

16. We will deal with the classification ground first, the timing ground second and the procedural ground last.

17. As the importations that are the subject of this appeal were at a time when the UK was still a Member State of the EU it is agreed that they were regulated by the provisions of EU customs law.

Preamble

18. Prior to the hearing we received:

(1) A 3,626-page bundle that included the Further amended grounds of appeal, HMRC’s amended statement of case and further response, two witness statements from Mr James Hickling, Head of Finance, two from Mr Jeremy Tennant, Finance Administrator, for QHH, and a witness statement from Officer Taskin Katib for HMRC. All deal with matters four or more years after events. There were also many documents and correspondences between the parties (and the Tribunal). Given the procedural ground, some of that will require to be traversed. This bundle also included skeleton arguments from both parties.

(2) A 3,952-page legislation and authorities bundle containing worldwide, European and UK materials.

(3) A suggested reading list from QHH which greatly helped us to navigate the bundles.

19. During the hearing we received:

(1) The visit report from 2 October 2019 prepared by Officer Katib contemporaneously. As we said at the time, this ought to have been disclosed well before the hearing but, in the absence of any objection and the lack of prejudice to QHH, no issue about its admittance arises. Indeed, as we shall see, it proved of benefit to QHH as well as to the Tribunal.

(2) A short 82-page supplementary bundle of authorities.

(3) An agreed statement of facts about the RBS.

(4) An example RBS with a banner.

(5) An RBS in the form it was at importation into the UK in a cardboard box and zip-up bag. In this form, the RBS consisted of a number of separate components: the aluminium base cassette with plastic end pieces, a short plastic sheet to which a banner could be attached, the spring and the aluminium stand and top rail.

20. We also received, without objection and alongside the agreed facts, a presentation of an RBS and how it fitted together (with said attached example display graphic) by Mr Dallow for QHH.

21. Finally in terms of documents, before the final day, we received written submissions from both sides together with further authorities. We are pleased to record that the written submissions themselves did not substantively exceed 25 pages each. All of this, with everything we received in the hearing, was helpfully consolidated into a single 299-page bundle by QHH.

22. We are very grateful for the way in which the voluminous documentation has been managed and presented in this case. In essence, aside from documents arising in the hearing, we had three bundles: Documents, Legislation/Authorities and (in this case) closing submissions with materials. That is as it should be. It greatly assists the Tribunal to have documents in this way, which is why the standard-case directions from the Tribunal require this.

Findings of Fact

23. The following are our necessary findings of fact for our analysis and conclusions in these appeals.

(i) Witnesses

24. We heard from all three witnesses from whom we had statements in the order we set out above [18]. Each was cross-examined. All were honest and doing their best to assist the Tribunal. Regarding Mr Hickling, we accept that he would not have said certain things to Officer Katib on the telephone prior to, and at, her visit to the premises on 2 October 2019. All witness statements were made some four years or more after events. Officer Katib and the Tribunal have the benefit of her contemporaneous visit report. If therefore there is a dispute between Officer Katib’s visit report and Mr Hickling’s (or any witnesses’ including Officer Katib’s) evidence, we prefer the content of the report.

(ii) The role of QHH

25. QHH is the holding company that sits atop a VAT group above two subsidiary companies that it owns. Those two are Innotech Digital and Display Limited (‘IDD’) and Wigston Paper Limited (‘Wigston’). IDD is important to the facts of this appeal. Wigston less so.

26. QHH, IDD and Wigston share directors in common. They also share a common VAT number. They each have a unique Economic Operators Registration and Identification number (‘EORI’) which is a requirement and (unlike a VAT number in a VAT group) unique to the person registered. QHH’s EORI is their VAT number with 000 as a suffix. IDD’s is the same VAT number but with 001 as the suffix. Wigston has 002 as the suffix.

27. On 18 September 2014 Mr Tennant applied for an EORI for IDD. The subject in the email attaching the application to HMRC was, “V09 1030 EORI Application Quantum House-Holdings” followed by QHH’s VAT number. That was an application for IDD to receive an EORI number. The body of the email states:

“Please see attached application for an EORI number, it would be appreciated if this could be expedited as soon as possible as we have goods at port awaiting clearance, our old VAT number has been cancelled due to a VAT group registration.”

28. HMRC replied on 25 September 2014. They said:

“In order to continue to process your application I will require the Main Group Representative of the VAT group to be EORI activated first, in order to process any group member applications.”

29. An instruction on how to do this was given. The Main Group Representative of the VAT number was, we infer from its EORI ending 000 and that it was the holding company and not a ‘group member’, QHH.

30. On 26 September 2014, after that task had been completed HMRC provided the EORI for IDD ending 001 and with the description “(Group Member)” .

31. It is immediately apparent that the intertwining of companies within a VAT group (with a main group representative and group members) and the required order of companies to seek EORI numbers can lead to some confusion as it did here.

32. IDD import raw materials such as aluminium sheets and RBSs into the UK for onward sale. Wigston import creative raw materials in sheets for onward sale. QHH do not import anything on their own account.

33. As recorded in Officer Katib’s visit report under the heading Main business activities Your role in the Supply chain (where ‘Your’ is QHH):

“Holding company for Innotech and wigston papers. Holding company does no trading. Just holding company for both … in 2013 group structure changed. 1/1/2014 [IDD] became own legal entity with EORI … 001. Wigston … with eori number … 002. Both will become part of holding company but own legal entity and imports under own EORI number.”

34. We are not satisfied that the final sentence qualifies what comes before it, in the sense that it doesn’t specifically describe QHH as actually making imports. Overall, we find that what is recorded was the extent of what was said about the relationship between QHH and IDD and Wigston and, dates aside, is accurate. The Sage spreadsheets produced before us by Mr Hickling confirm the nature of QHH as a non-importer. The various documents such as invoices from suppliers show IDD as conducting the trade. Had any detail, such as 90% of QHH business imports being for IDD, been provided in those terms we would have expected to see it in the visit report. Any such detail provided four years later by HMRC is unreliable. Given our findings overall about the role of QHH it is inherently improbable such detail was provided. What is likely, and we find, is that Mr Hickling said, as he told us, those figures related to the consolidated accounts. As no note is made at the time, the reference to “90% of QHH business imports” presented by HMRC is in error.

35. As we have found, the EORI numbers were activated somewhat later in 2014 (see [30] above) and we accept QHH was the holding company for IDD and Wigston and did no trading itself.

36. Officer Katib recorded that when goods have been shipped to the UK from a supplier:

“Agent notified. Agent request documents. Documents provided to agent with instruction of values and CMCD to declare. Agent makes declaration. Company holds deferment account. VAT/duty paid. Goods released from customs … Paperwork received and C** checked. [Mr Tennant] responsible for this on both company.”

37. The CMCD is the Tariff Commodity Code. The staff did not appreciate that the code might change for a particular good and, as a result, checks were never made in this respect. In terms of binding tariff information (‘BTI’) IDD had one from HMRC for RBSs which expired on 16 December 2016 showing 0% duty. The code was 9403 2080 00. This was relied on post expiry, and they continued to use the same code at 0%. The same is true of their competitors, at least until 30 August 2018. It was only in March 2019 when French customs told the Appellant’s staff that the classification code had changed to one with duty of 6%. No application was made to amend the customs declarations at that point to show code 7616 9990 99 and pay the duty and VAT accordingly.

38. The company that held the deferment account and paid the VAT and duty was IDD. IDD also retained and paid the Agents to act for them. It was common ground that the Agents acted on a direct basis, that is on behalf of their principal. We find that the Agent was instructed by IDD and IDD was its principal . “Both company” at the end of Officer Katib’s note (see [36] above) is a reference to IDD and Wigston as the two companies that import.

39. The instructions were given to the Agent by Mr Tennant as to which code to use and the values. Copies of the customs declarations were received afterwards but were not checked through in the detail of what was in each box, beyond the amounts themselves. Mr Tennant told us, and we accept, that IDD was intended to be the importer for customs purposes. However, he at no stage spotted that QHH appears alongside its EORI number. He said, “If I had looked at these documents, I would probably have thought that this was somehow caused by QHH holding the group VAT registration for [IDD].” He did not see this as an issue of consequence, as opposed to simply an inaccuracy. He further said, and we accept, “What Officer Katib did was very helpful at the time bringing education in terms of relevance and importance of all the boxes”.

40. Mr Hickling was certain that IDD gave clear instructions to the Agents to, “make imports in the name of IDD” although no documents were now available to confirm this. His conclusion was that the Agents made an error, and this could be linked to the fact that “[IDD] uses the QHH VAT number and that the EORI numbers for each of the group companies is derived from the QHH VAT number.” Due to passage of time the written instructions could not be located by QHH, IDD or the Agent. The Agent, in a letter requested for the appeal, on 28 May 2024 said:

“From our records I can see that in 2017 we did declare imports for [IDD] using QUANTUM HOUSE HOLD EORI … 000 although I do not see any explanation or note to explain why this was done.”

41. Additionally, from the records presented to us, the Agent was including the name of the consignee as IDD on the C88 at the same time it was inputting QHH’s EORI.

42. On balance we find that the use of QHH and its EORI was an Agent’s error but one that was not spotted by QHH or IDD when it should have been. The businesses had copies of the customs declarations where this is made clear given the unique QHH EORI is used. We find that it was not something that troubled anyone at the time at QHH/IDD (or up to the point of the appeal to the Tribunal) from the managing director down. The customs debt would have been paid for by one of the group of companies. Indeed, such duties and VAT that were paid where QHH’s EORI was used usually came from IDD’s deferment account (except where the Agent’s deferment was used, which we were told was typically when there was insufficient headroom in IDD’s account). Mr Hickling told us in relation to correspondence that he did not think there was anything curious in receiving it in the name of QHH rather than IDD “It was the same VAT group”.

43. As Mr Tennant candidly accepted in response to questions by the Tribunal about QHH appearing on the customs paperwork he did not think it was odd at the time:

“[QHH] was the owner of the VAT group. There was an element of confusion. In recognising the importance of what we are discussing now and in hindsight I agree it is of great importance, but at the time QHH was the group owner and the C79 each month was in the name of [QHH], the importance then was not so relevant to me.”

44. That thinking permeated QHH/IDD and, as we shall see, explains why no one attached any importance to disabusing Officer Katib at the meeting on 2 October 2019 that QHH was not in fact the customs declarant and why Officer Katib cannot be criticised for thinking QHH was importing for IDD. All parties proceeded on the basis that QHH was liable for the customs debt.

(iii) The RBS at the point of importation

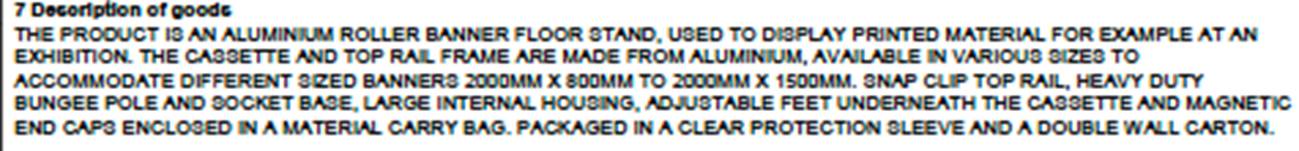

45. We set out, in full, the statement of agreed facts which the Tribunal gratefully adopts as its findings as to what the RBS is and contains at the point of importation and what it does not:

“What is included at point of importation

The product has an outer carton made of cardboard. Inside the carton is a bag made of woven polyester fabric, with a carrying handle. Included in the carrying bag are the following items:

Common to all the types of stand is a base cassette and top rail frame which in this case is made from aluminium.

The cassette and outer housing, in this instance are made largely of aluminium but with certain plastic components, which contains a pre-tensioned spring mechanism made up of a plastic tube and a steel spring which is locked by a removable steel pin.

The cassette and outer housing also has feet attached to the body to provide stability when it is placed on the floor:

· A plastic sheet (“the lead paper”) is attached to the plastic tube. The sheet includes a self-adhesive strip which can be removed to allow the attachment of a printed advertising or display graphic. The pre-tensioned spring mechanism enables the banner to be deployed and retracted automatically. If the locking pin is removed before attachment of a printed graphic, it would render the product unusable as the sheet would not any longer be accessible to attach the printed graphic.

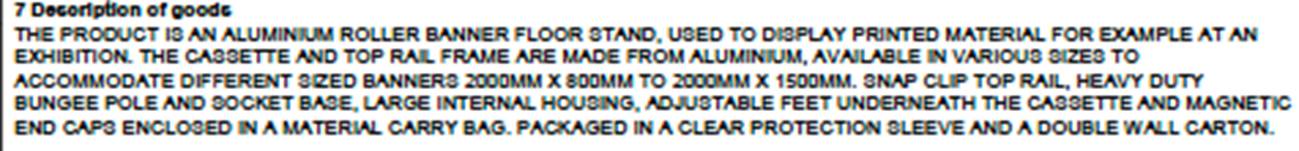

· The top rail is made of aluminium with plastic end caps which is to be subsequently attached to the printed graphic.

· The pole is made of aluminium tubular sections connected by steel connectors and an elastic bungee cord, with a plastic connector on the top section which when assembled provides the support to hold the printed display or advertising graphic in place against the downward force of the spring mechanism.

Not included at point of importation

At the point of importation and indeed when sold by [IDD], the display stand does not include a printed advertising or display graphic. Rather, the printed advertising or display graphic is provided later. There is a small section - the lead paper - on which the printed advertising or display graphic can be attached.”

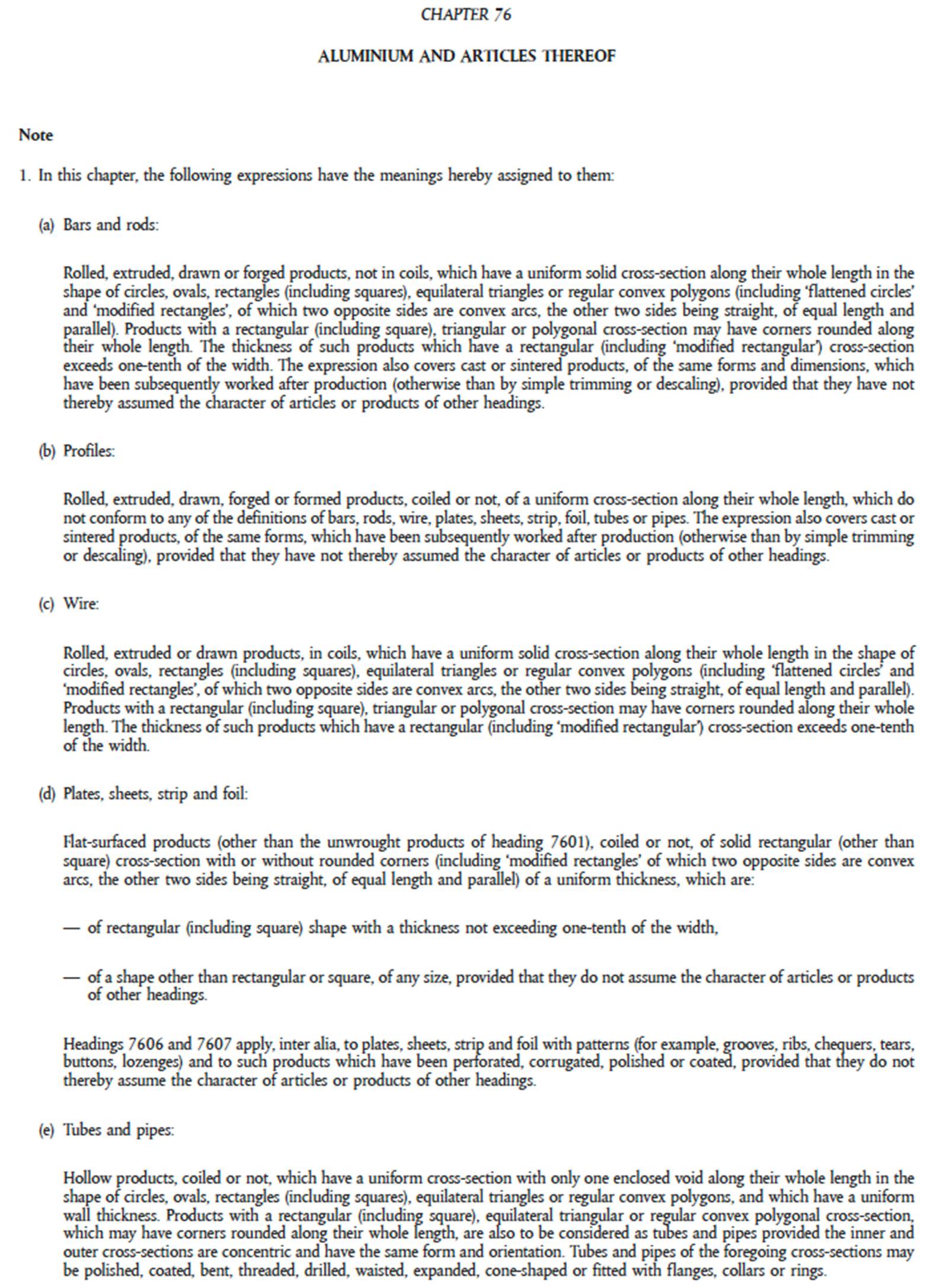

46. The example RBS cassette and outer housing is shown as follows from the demonstration Mr Dallow gave us in a picture taken by us:

47. From the agreed facts and the photograph of the cassette it can be seen at the point of importation:

(1) the cassette, the pole and the top rail frame are in a bag. The bag is in a carton

(2) The top rail frame is made of aluminium

(3) The cassette is largely made of aluminium but some components within are made of plastic, and the spring mechanism is plastic and steel

(4) The pole is made of aluminium connected by steel connectors and using an elastic bungee cord

(5) A self-adhesive strip is attached which can be removed to allow the attachment of a display graphic or printed advert.

48. The display graphic or printed advert are not included at the point of importation.

(iv) The issue of an Explanatory Note to the Combined Nomenclature

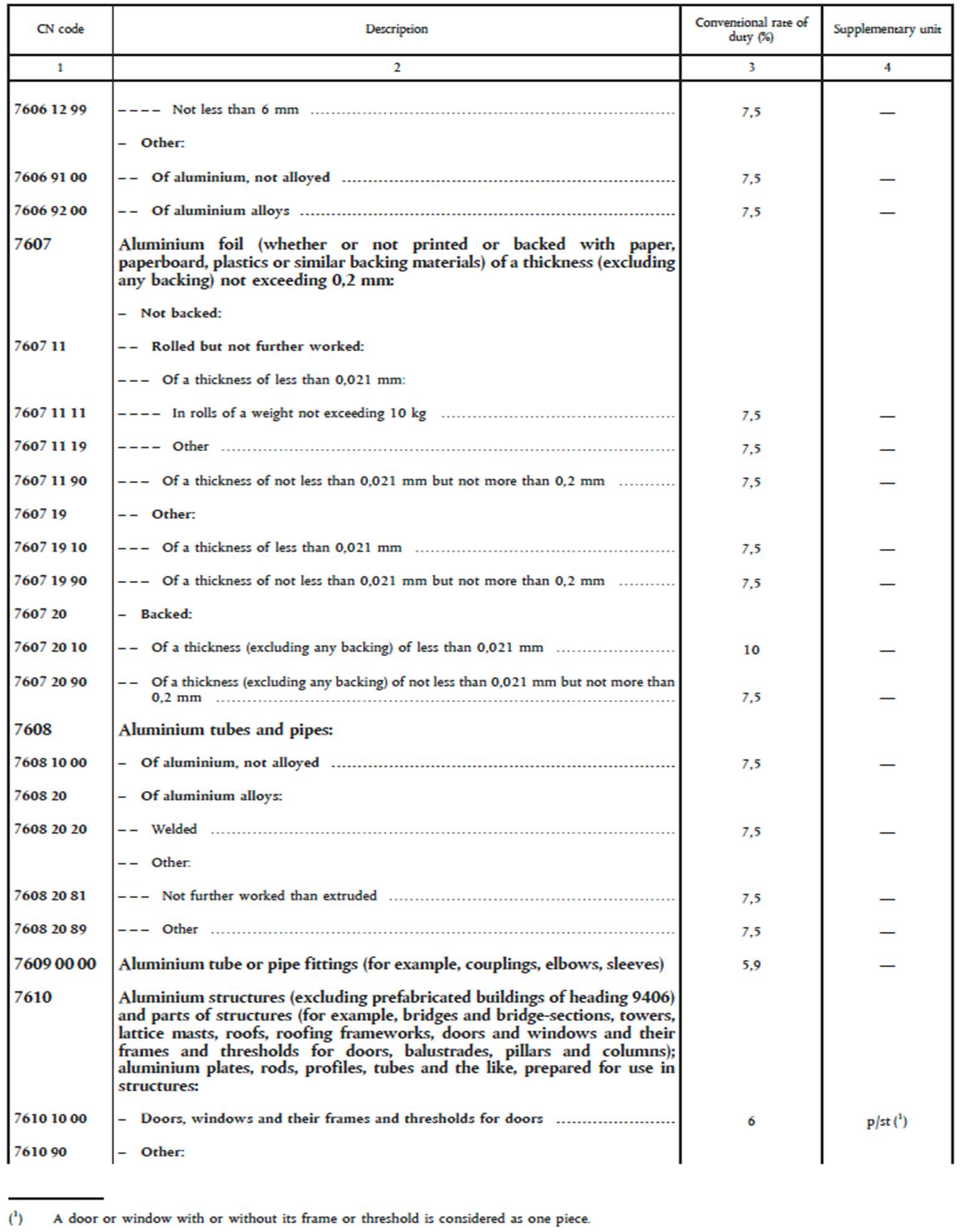

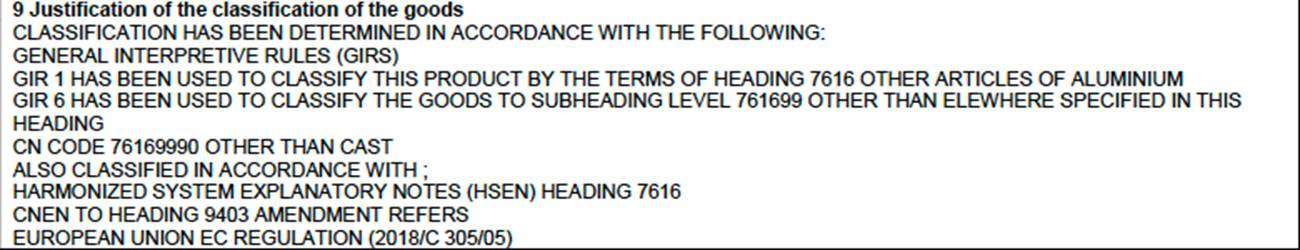

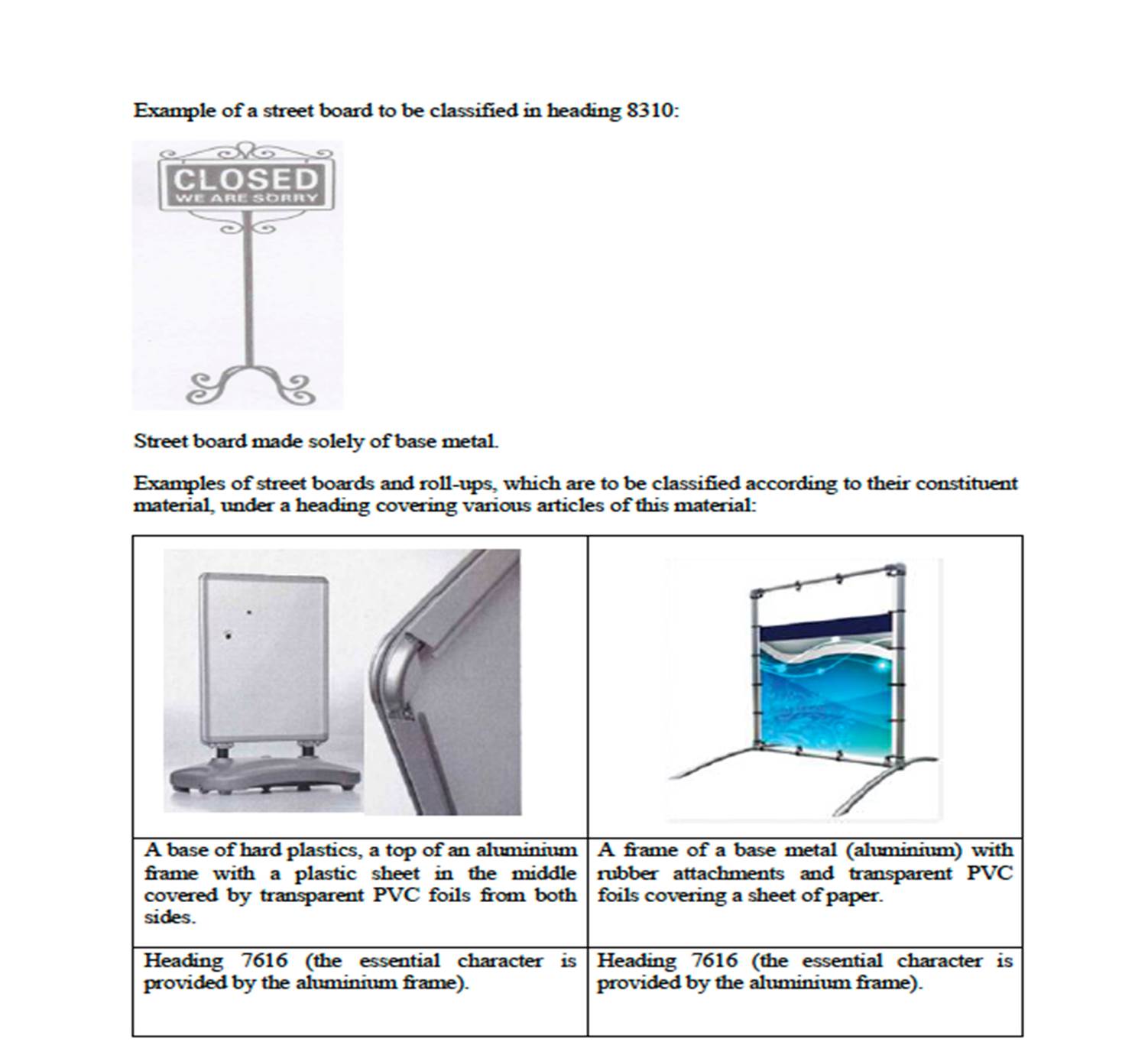

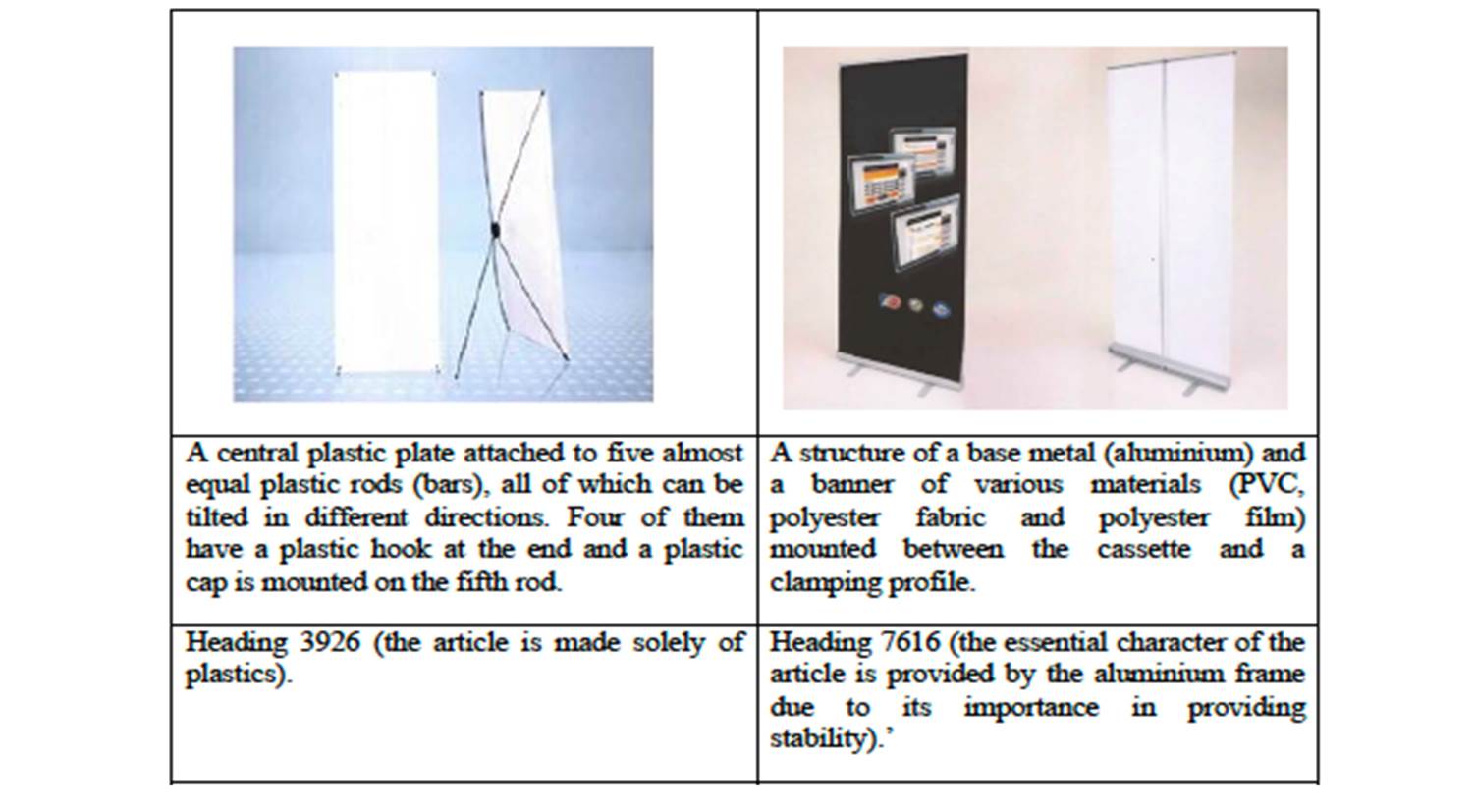

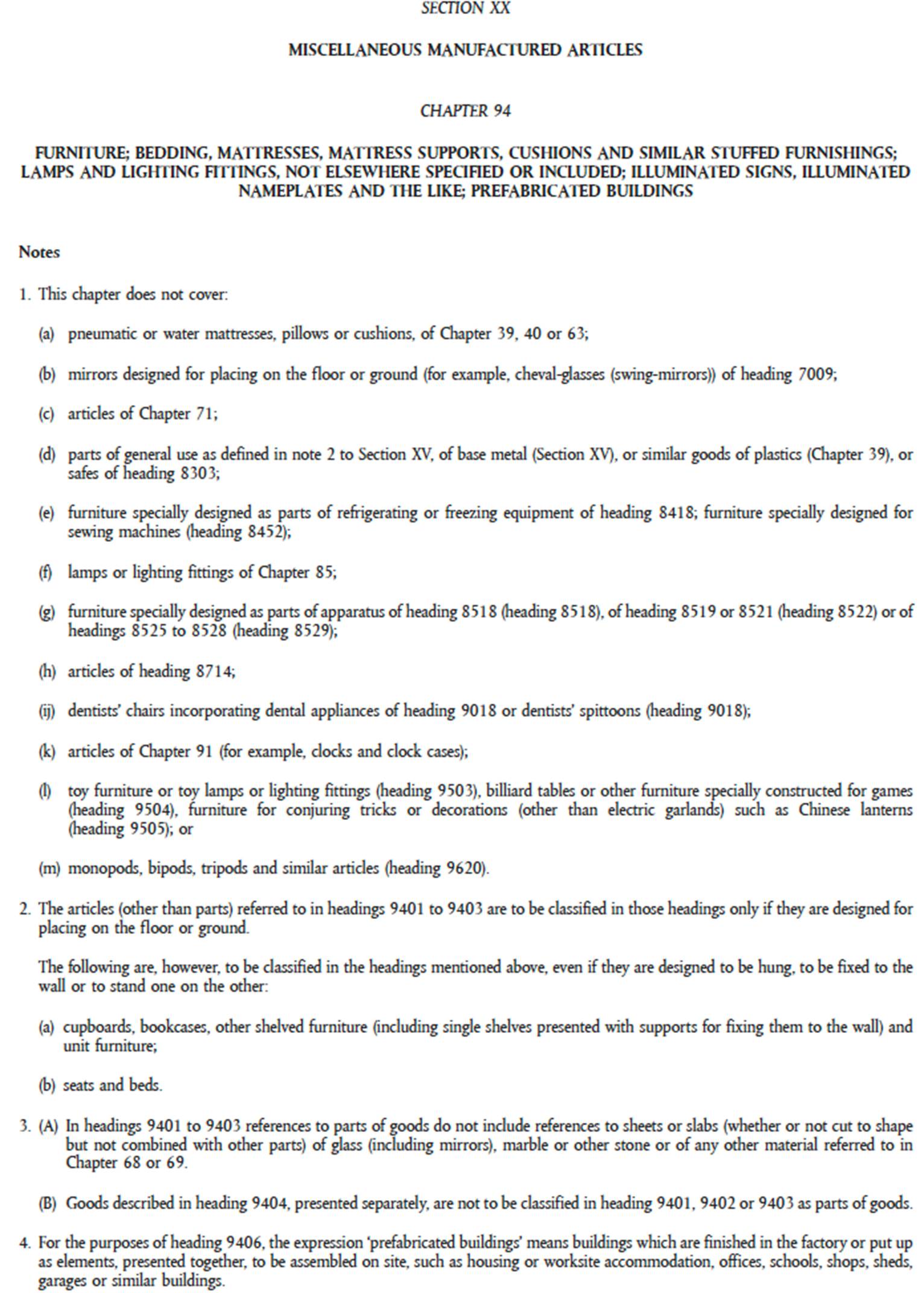

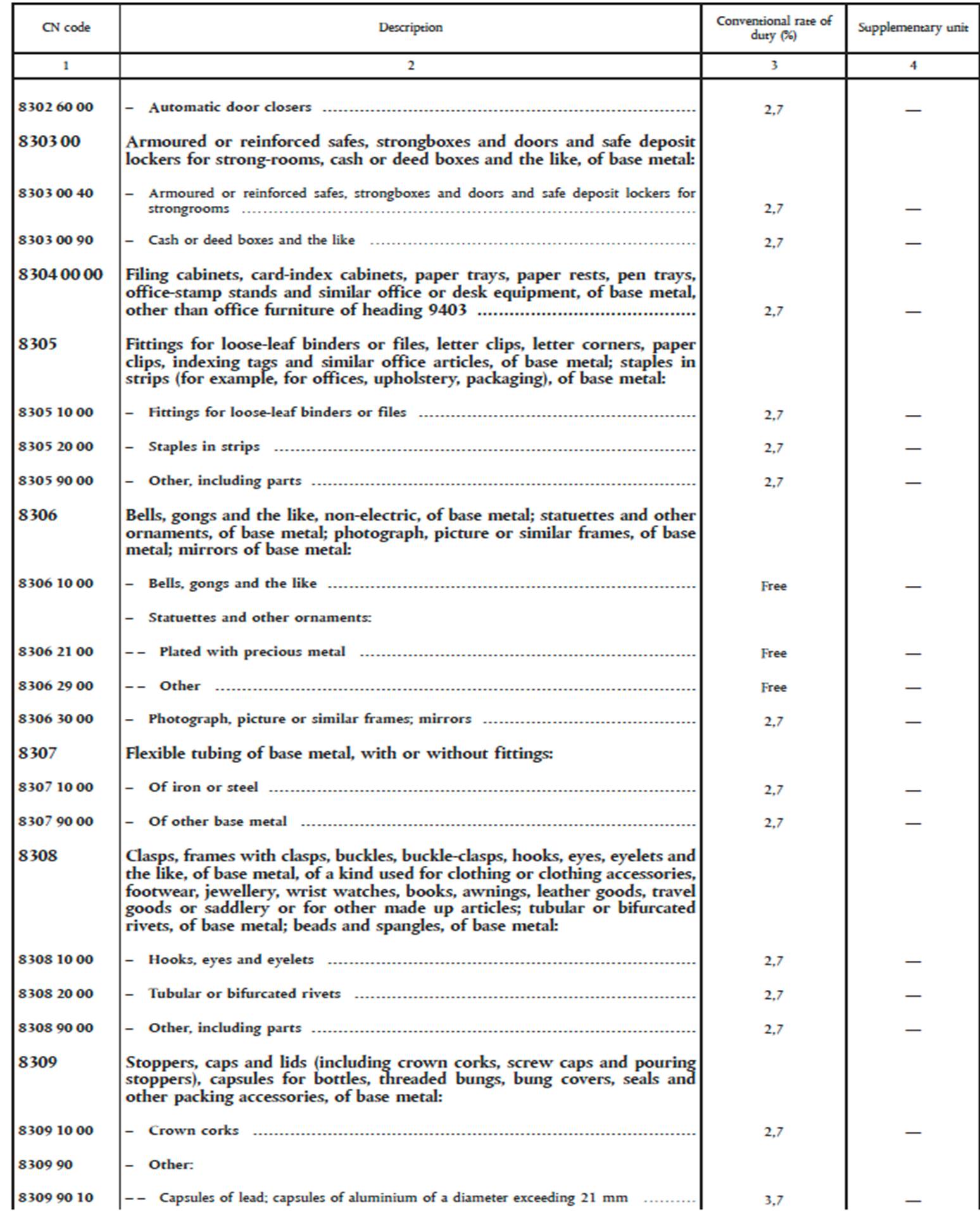

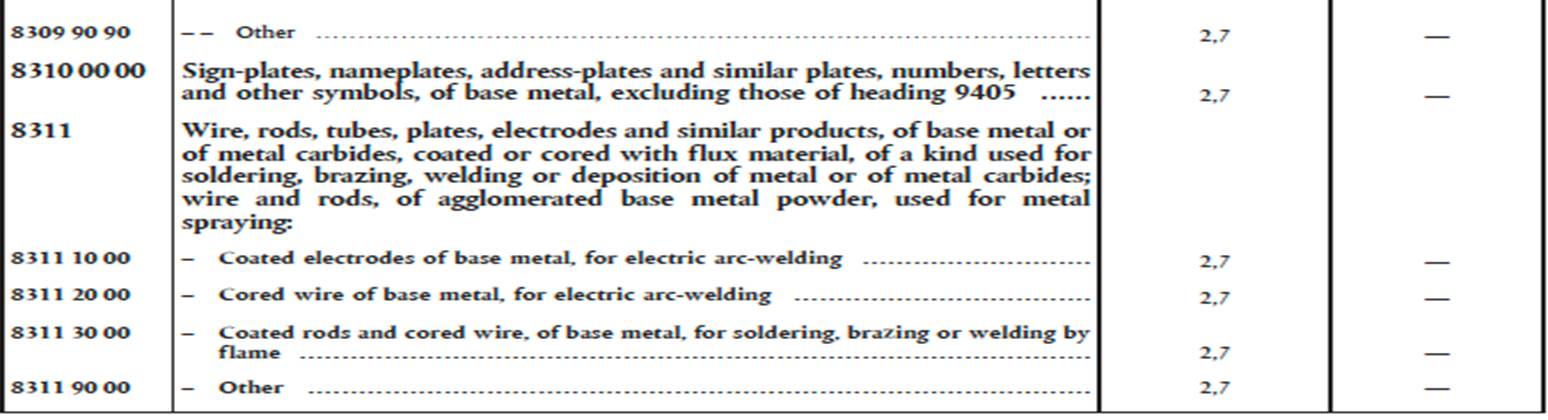

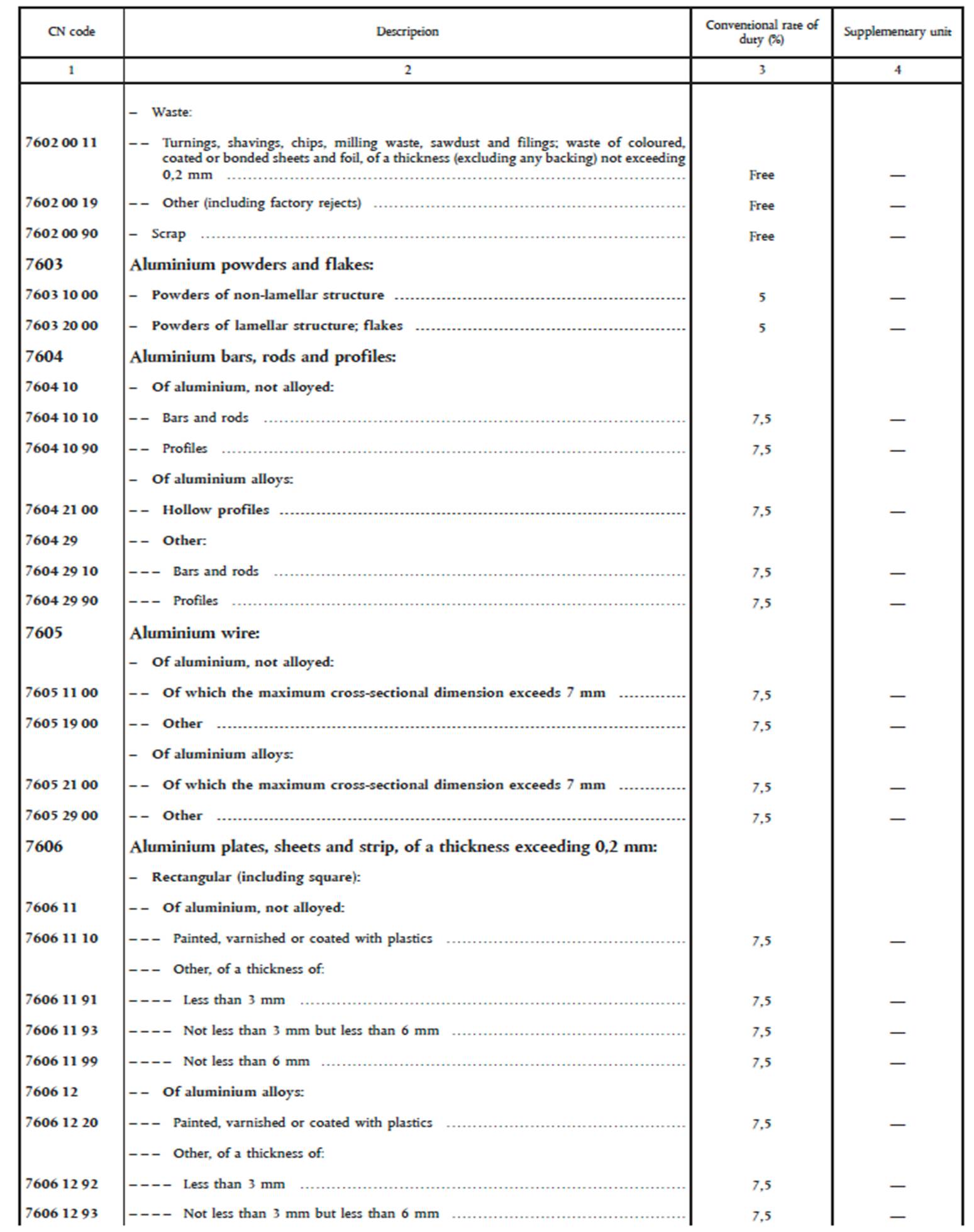

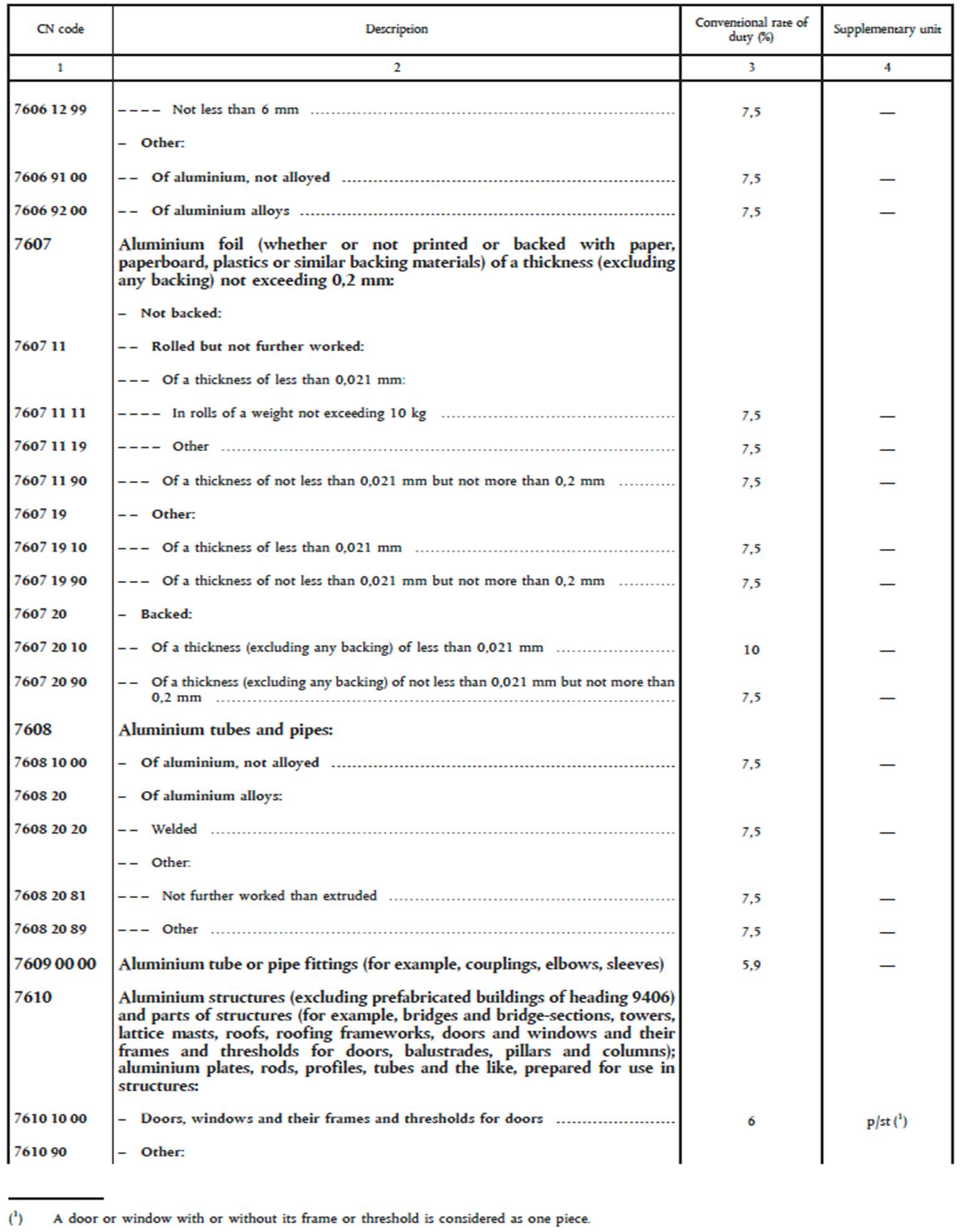

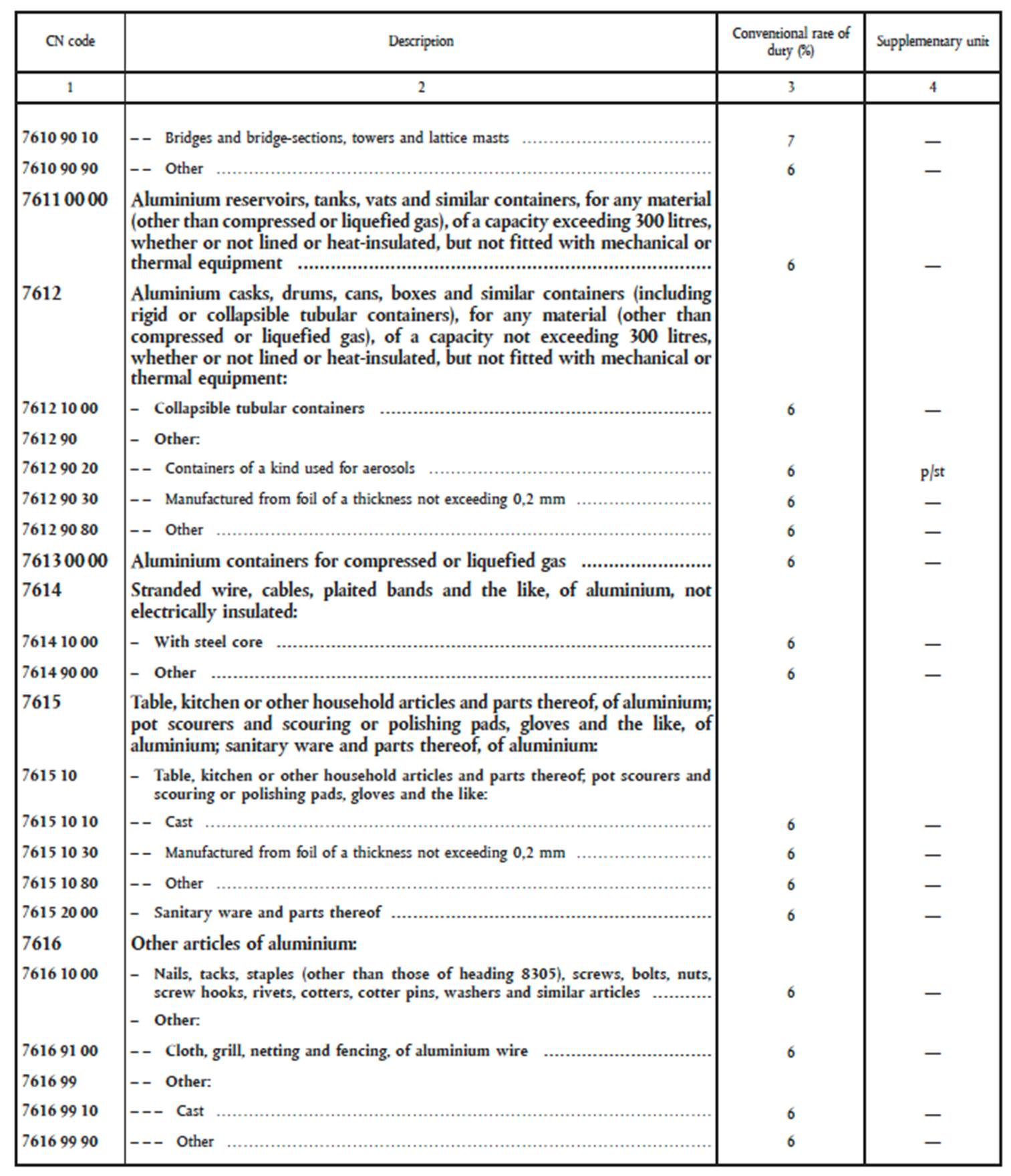

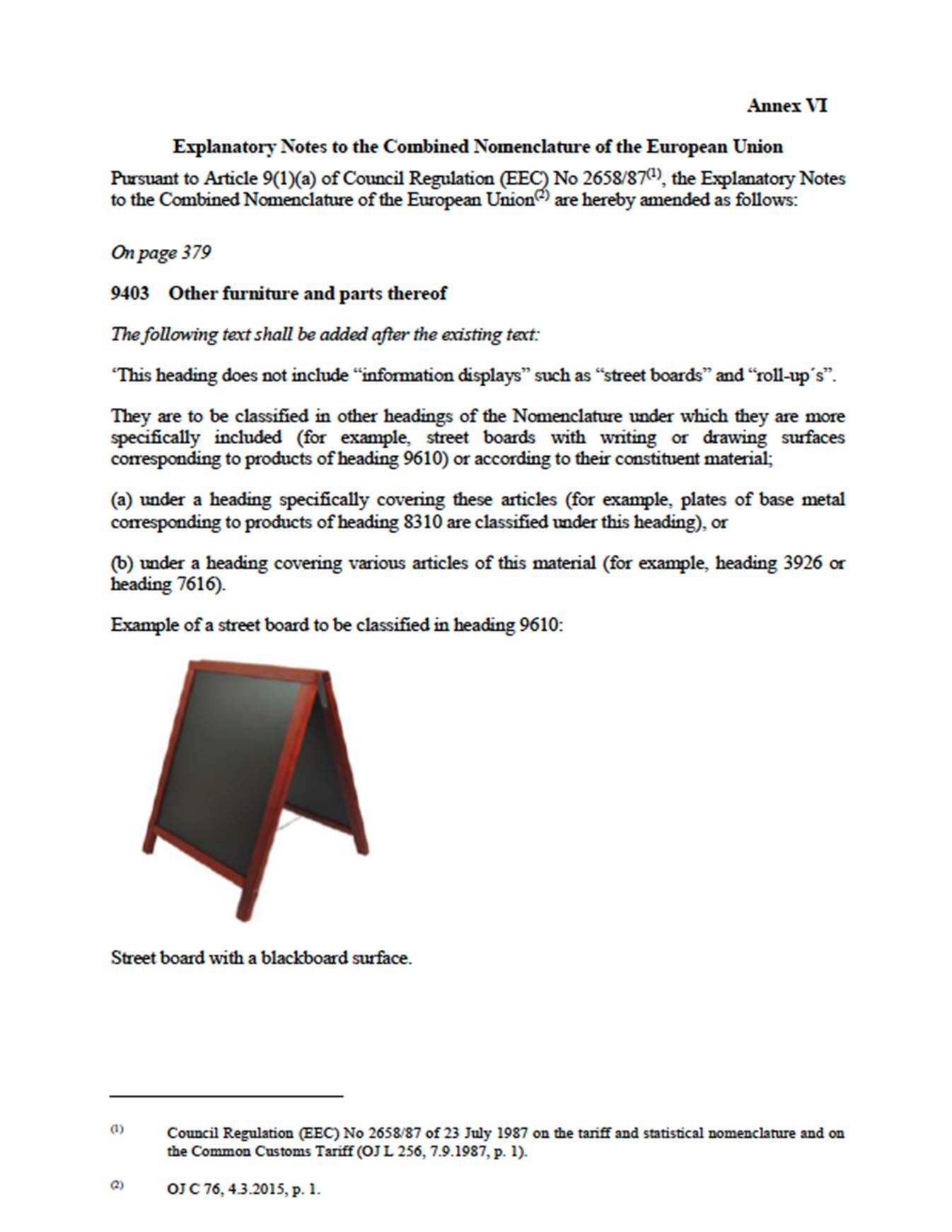

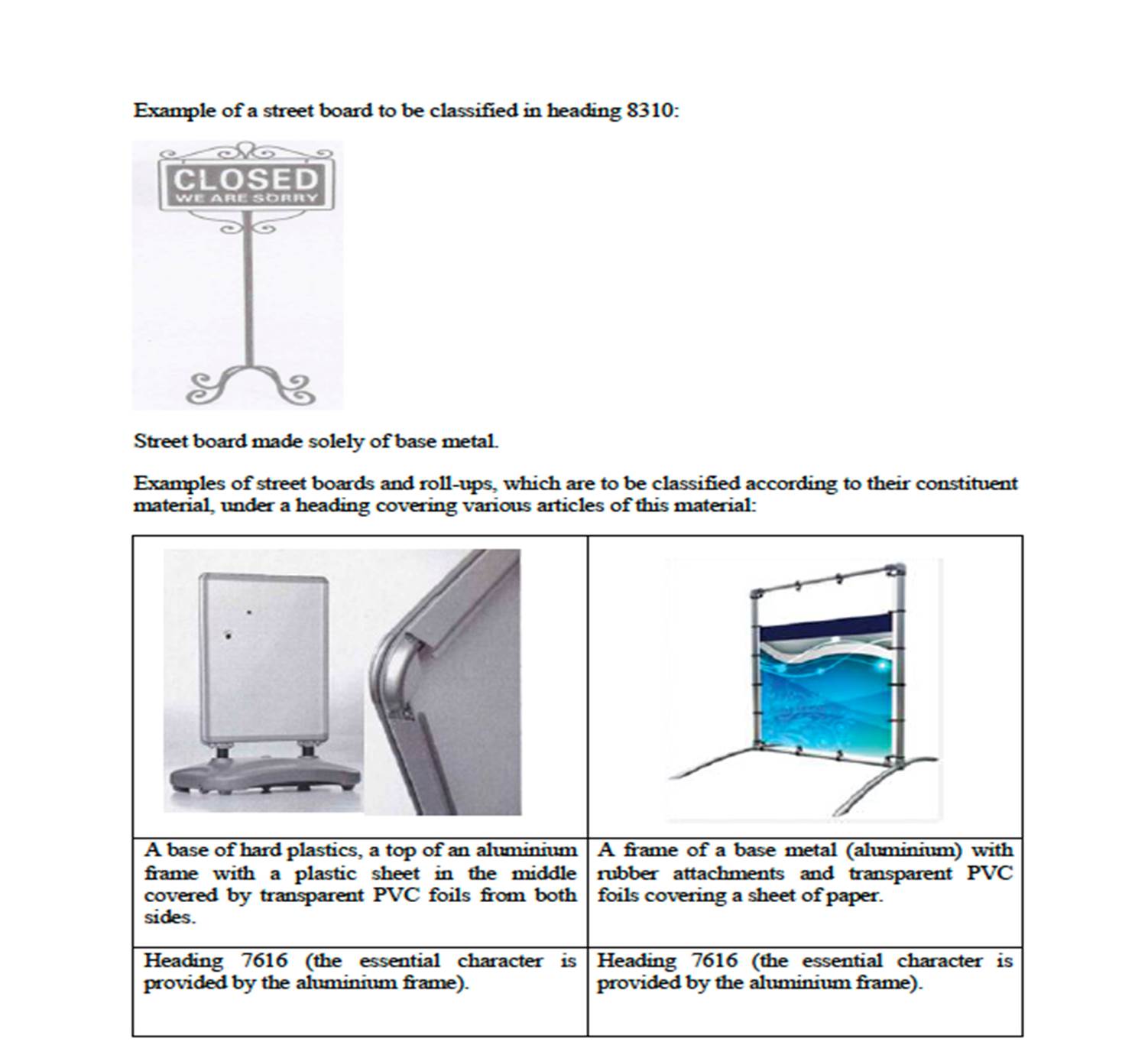

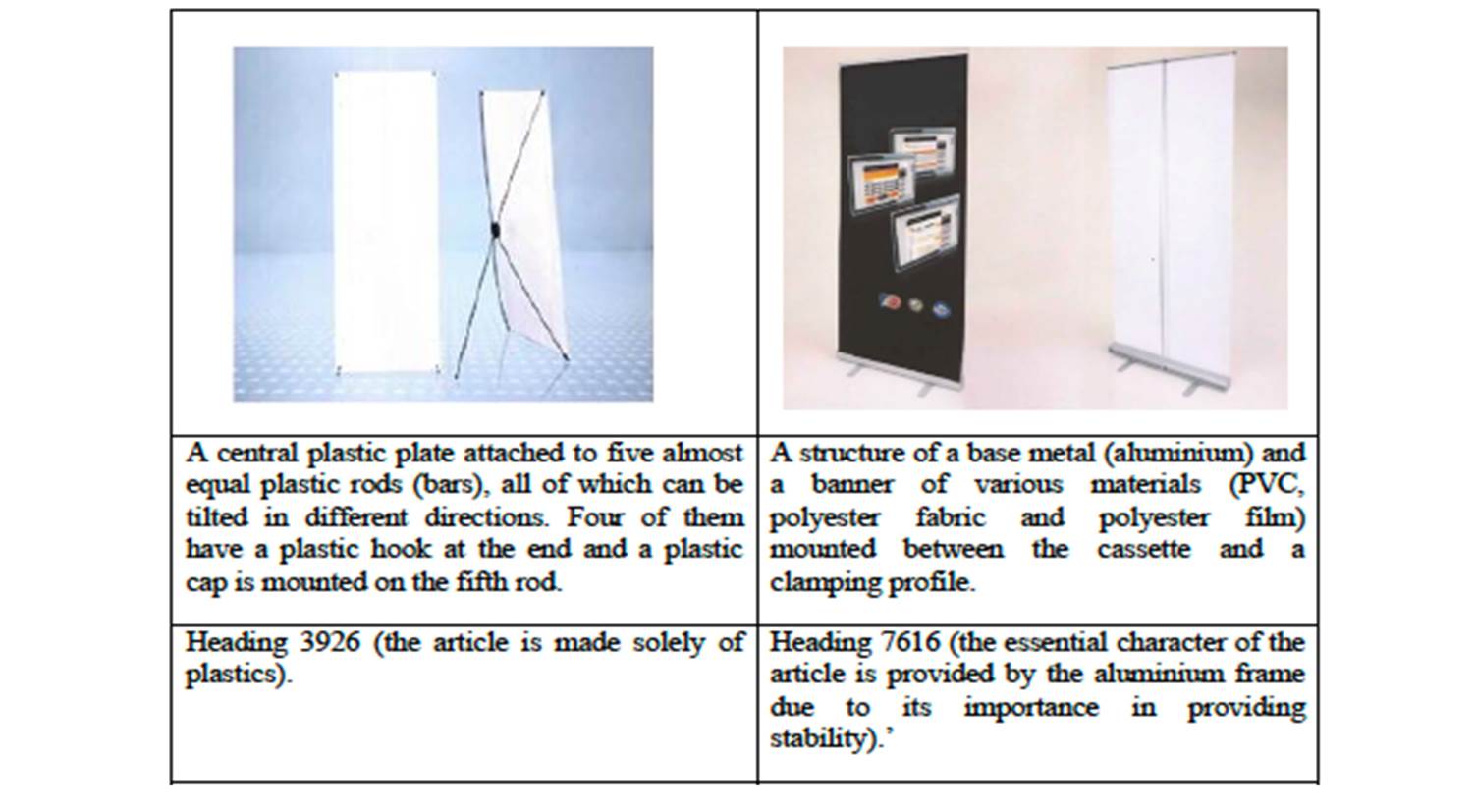

49. As noted above, on 30 August 2018 a CNEN was published in the Official Journal of the European Union. This advised that the commodity code 9403 2080 00 did not include “information displays” such as “street boards” or “roll-ups” and that these should be classified where they are more specifically included. Instead, where the essential characteristic was that of an aluminium frame, the commodity code should begin 7616.

50. The full text of the CNEN is set out at Annex 1 to this decision.

51. The effect of the CNEN came into force on the day it was published. QHH and IDD did not appreciate this change. No processes were in place to check for changes such as this. No amendment was made or sought to be made to the customs declarations at any point.

52. As a result of the CNEN, HMRC concluded that the correct commodity code for RBSs was 7616 9990 99 for imports made from 31 August 2018 onward.

(v) The importations, the declarations and the errors on the inputting of the Economic Operators Registration and Identification number

53. The relevant importations of the RBSs took place between 31 August 2018 and 10 October 2019. For all of those (as well as those for some two years prior to 31 August 2018) QHH was named as the ‘consignee’ on the customs declaration in the UK and as the company responsible for the customs debt of any duty arising because its EORI was used.

54. The Agent used the system known as CHIEF to electronically input the data onto C88s .

55. On the C88s that we were shown and that are relevant to this appeal Box 8 was completed with QHH’s EORI, that is with the suffix ending 000 after the VAT number. Underneath that was completed the name and address of the consignee, in each case IDD and the shared physical address with QHH.

56. The name and address should not have been used as it is only to be added if the country code is other than GB, the identity is GBPR or there is a paper declaration. None of those applied in relation to any C88 we are concerned with.

57. Box 14 was completed in the name of the Agent with its EORI and code [2] denoting direct representation.

58. The classification code in Box 33 was 9403 2080 00.

59. In box 48 a “DAN” number is used. The “DAN” is the deferment account number. That is the account from which the Agent will instruct the payment of duty and VAT (if any) to be made from. In this case the DAN number was that of IDD (except as noted above). A DAN account can be used by anyone as long as they have the holder’s permission. It does not assist in determining who the declarant is.

60. In the document headed “CHIEF Import Entry Acceptance Advice” generated after the C88 details are inputted the consignee is only referenced by the EORI number and the name of the holder, in this case, QHH. That emphasises the pre-eminence of the EORI.

61. In March 2019 the French Customs authorities told the staff at QHH/IDD that they were using the wrong customs classification code. As a result, QHH changed the code for all imports into the EU other than the UK.

(vi) The Customs and International Assurance visit of Officer Katib on 2 October 2019 and the issue of the C18 Notice

62. On 11 September 2019 Officer Katib tried to contact QHH by telephone. She did not have success.

63. As a result, on 12 September 2019 Officer Katib wrote to QHH detailing the proposed visit. The reference was CFSS-3318528.

64. The company being proposed to be visited was set out clearly, “Company Quantum House Holding Ltd.” The reasons for the proposed visit were clearly set out including to ensure the correct amounts of import duty and VAT are declared and to check that:

“the company record’s and systems concerned with the import and/or export of goods are sufficient to provide the information required by EU regulations.”

65. That encompassed QHH’s processes including the use of its EORI.

66. That letter was not received by QHH at the time.

67. As a result of hiring a consultant, who concluded that the position was inconclusive, on 20 September 2019 Mr Phil Walker, a director, using his IDD email address, and with the details of IDD, submitted a request to the classification team at HMRC. However, against the request for “VAT registration or EORI number (if registered)” he simply put the VAT number rather than any unique EORI.

68. The question he asked was, “Please could we be put in touch with whoever the specialist is covering the importation of aluminium portable display stands. It is a question of what we should do in circumstances where we are unclear about the particular customs categorisation of the main products we sell. It turns out some of your guidance may have changed (so the product has moved into a different category without us knowing it) but our main competitors in market appear to be unaware of it.”

69. On 23 September 2019 Officer Katib telephoned Mr Hickling.

70. Mr Hickling told us he did receive Officer Katib’s letter of 12 September 2019 but only the day after her visit. In fact, in an email from Officer Katib to him on 23 September 2019 she attaches the letter, schedule and fact sheet CC/FS1g. The schedule requests several items including:

“Import clearance instructions issued by your company to the freight agent

…

Copy of the customs import declaration (C88) …

…”

71. There was also a request for a detailed discussion about how QHH ascertains the correct commodity code and copies of any binding tariff information certificates (if any).

72. In reply on the same day Mr Hickling confirms receipt that day of the hard copy posted letter.

73. On 2 October 2019 between 09.20 and 17.00 Officer Katib visited the premises of QHH. These times were recorded on her visit report. Officer Katib (with a trainee) met Mr Hickling, financial controller, Mr Phil Walker, managing director, Mr Dallow, product specialist, and Mr Tennant, import/export finance manager, all of whom were presented as QHH staff. We have already recorded some of our findings about QHH and IDD based upon what was recorded in her visit report (see [33] above).

74. Contrary to Mr Hickling’s recollection that the visit was over “two or possibly three days”, or, as recorded in his supplementary witness statement, “a substantial three-day visit”, it was a single day.

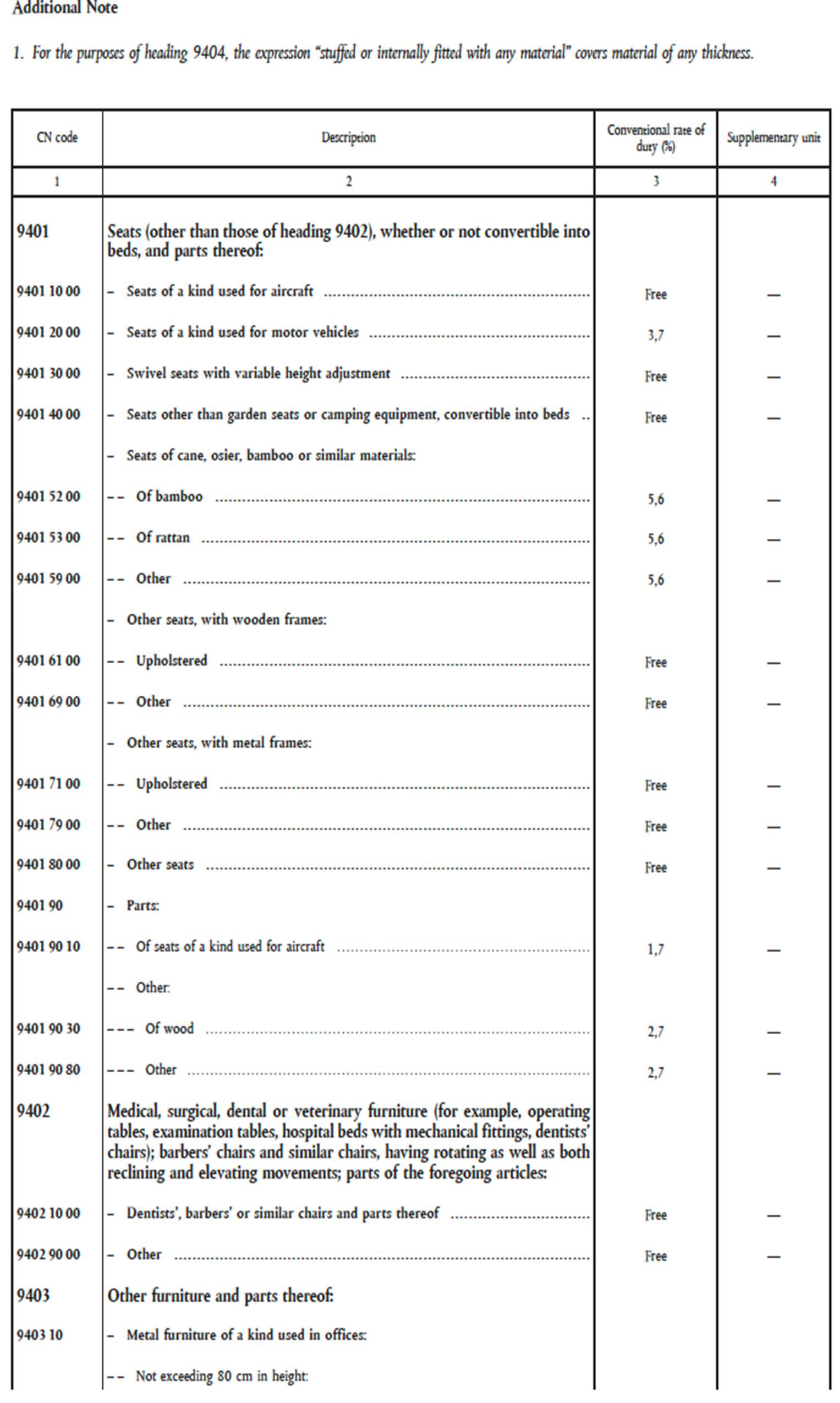

75. In her visit report Officer Katib notes the “Trader” was “QHH” and gives the correct EORI ending 000 underneath. Officer Katib records that she “Explained the reason for visit”. We have already set out what the letter of 12 September 2019 explained. It is inconceivable that QHH being recorded on the customs declaration and its EORI being used as such was not raised at all and we find it was. Mr Hickling has no memory of Officer Katib raising it and he told us:

“Had Officer Katib done so and asked whether Innotech was in fact the importer, we would have said absolutely “Yes” and done whatever was needed to amend the mistake on the entries.”

76. We accept Officer Katib’s evidence that it was not for her to question the business structure and if a decision was made to use QHH’s EORI on the customs declaration. Mr Hickling accepted there was a difference between commercial and customs arrangements. The question Mr Hickling would have answered in the way he told us he would was never asked. We further find, as Mr Hickling told us, that QHH not being the importer or customs debtor was “not expressly said in terms” to Officer Katib. Mr Hickling and other’s focus was on IDD during the visit rather than QHH and the customs classification rather than whose EORI was being used.

77. At the meeting Mr Hickling and Mr Phil Walker confirmed the group structure. QHH’s company house number was confirmed as well as its VAT number. As we have set out, Officer Katib recorded that QHH was the holding company for Innotech and Wigston and that QHH did no trading but was simply the holding company for both.

78. After some discussion Officer Katib and those she was meeting looked at an RBS. Officer Katib asked for material to get a “liability ruling” from HMRC to ensure the correct code was being used. Officer Katib showed everyone how to look at binding tariff agreements and other documents on screen.

79. Officer Katib made it clear to us, and we accept, that there was no deliberate non-compliance, rather a lack of education. That related both to the commodity code being used, which had changed, and the use of QHH’s EORI.

80. At and after the meeting, we have no doubt at all that everyone there from HMRC and QHH/IDD was aware that QHH’s EORI had been used. It is quite clear from the visit record that what was troubling Mr Phil Walker and others was the prospect of a large debt because of the change in customs code, not whose EORI was being used.

81. On 6 October 2019 Officer Katib requested two Live Liability Rulings (‘LLR’) from HMRC’s Tariff Classification Service (‘TCS’). Within those requests under the heading “Importer name” was inserted “QHH”. One was what the correct commodity code should be up to 30 August 2018 and one for afterwards.

82. On 10 October 2019 Officer Katib received a fax from the TCS with both LLRs. The conclusions of the then current LLR were communicated to QHH by email of the same date. The attachment was called “20191010 Quantum House Holding Live Ruling result letter.pdf”. In the body of the email Officer Katib wrote:

“I have the results of the Live ruling. Please see attached letter.

…

Please note:

· Your company has imported goods of that description …

…”

83. In the ruling it had next to “Holder” “QHH”. Under the heading Decision in her letter Officer Katib wrote that the TCS ruled that the RBS fell under commodity code 7616 9990 99 for 31 August 2018 and going forward (but in a separate ruling the old classification for prior to that date). Under the heading Justification the TCS set out that they had used the General Interpretative Rules (‘GIRS’) and GIR 1 was used to classify the product under heading 7616.

84. From 29 October 2019 the business continued its imports of RBSs but changed the EORI used to IDD’s rather than QHH’s.

85. On 8 November 2019 Phil Walker replied to Officer Katib. This was a detailed response concerned with the timing of the classification code change with no reference to QHH being the wrong person liable for the customs debt.

86. On 3 March 2020 IDD sought a further BTI by an application. In that application having described an RBS in similar terms to the agreed facts they wrote explaining how they had applied the GIRs:

“We consider that code 8302 4900 99 is the most suitable classification for this product. This code is for miscellaneous articles of base metals (including aluminium). This focuses on base metal mountings, fittings and similar articles suitable for furniture, doors, staircases and windows etc.”

87. At that point when the BTI was sought, it was not suggested that an RBS was furniture.

88. On 15 May 2020 QHH obtained BTI … 9991 confirming the proper classification code for RBSs was 7616 9990 99. HMRC wrote (in material part):

89. On 12 June 2020 that BTI was appealed by IDD, along with a request for an independent review, again requesting that the classification should be headed 8302.

90. On 24 July 2020 an independent review upheld the terms of the BTI. IDD did not further appeal the BTI.

91. On 1 September 2020 Officer Katib sent a “Right to be Heard” (‘RTBH’) letter, schedule and calculation for the period 31 August 2018 to 31 March 2020. The calculations identified QHH as the consignee and the amount due was based upon the classification code from the BTI. The letter was issued to Mr Walker at QHH with the reference ending 8528 (see [63] above). The schedule included the paragraph:

“You are reminded that as an importer or exporter, you are legally responsible for the accuracy of the declaration made to Customs …”

92. It ended:

“If you have any further evidence or arguments that could change this decision then please send them to me within 30 days of the date of this letter …”

93. On 29 September 2020 Mr Hickling wrote to Officer Katib in reply. The letterhead was IDD’s but the reference was that ending 8528. Nowhere did IDD suggest that QHH was not liable for the customs debt. There was an acceptance that the correct commodity code was 76169990 but the request was for any duty to be paid from March 2019 when QHH had been made aware by the French customs authority of the change in classification.

94. By this point HMRC and QHH both operated under the common assumption that QHH was liable for the customs debt. QHH’s EORI had been used on the customs declarations between 31 August 2018 and 12 October 2019. As far as QHH and IDD were concerned, they were part of the same VAT group, which meant QHH being liable for the customs debt was assumed to be appropriate, even if their EORI was used in error. On 23 September 2019 QHH had received Ms Katib’s letter setting out the reasons for her visit. On 2 October 2019 that visit was made to QHH for those reasons. Between that date and the issue of the RTBH letter nearly a year later not once was there a suggestion to Officer Katib that QHH were not liable for the customs debt. QHH/IDD assumed that they were. The amount of time that passed and activity between Officer Katib and QHH up to and including the issuing of the C18 to QHH meant that QHH through its words and actions in not telling Officer Katib that QHH was the wrong entity to be liable for a customs debt, had a crossed a line, cementing the common assumption that QHH was liable for the customs debt.

95. After a letter dated 6 October 2020 from Officer Katib, on 12 October 2020 HMRC issued the C18 Notice to QHH with a demand reference ending 5657. Officer Katib was the decision maker. In box 8 on the C18, QHH is set out as the ‘consignee’ with the number ending 2000 alongside it. The C18 Notice was issued under cover of a letter from HMRC of the same date. That was sent to QHH. It informed QHH they could ask for an independent review or appeal to the Tribunal. Mr Hickling accepted that when the C18 was issued to QHH they thought it [IDD, Wigston and QHH] was “all one group” and that, “the VAT group was QHH”.

96. On 20 October 2020 QHH were aggrieved by the issue of the C18 and sought an independent review. That request was from Phil Walker under the reference ending 5657. Once again, no suggestion was made that QHH were the wrong target of the C18 request. Indeed, in the covering email seeking the review into the C18 issued to QHH Phil Walker said:

“Further to HMRC’s letter of 6 October and the C18 demand of 12 October, the company hereby asks for an independent review of HMRC’s decision in this matter.”

(vii) QHH’s appeal against the issue of the C18 Notice

97. On 27 October 2020 HMRC communicated that the independent review into the issuance of the C18 Notice with the reference ending 5657 would be undertaken.

98. On 2 March 2021 an officer of HMRC unconnected with the case completed his review. In his letter of that date he described the key point in issue as being, “… whether the debt should be calculated from 31 August 2018 as Officer Katib has calculated it or from March 2019 as QHH contend.”

99. It will be immediately apparent that neither the classification ground nor the procedural ground was raised during the independent review. Rather the focus was upon the timing ground. That is an acceptance, freely given, that QHH did not believe it was anything other than liable for the customs debt reflecting, as it did, QHH’s position from before and at the time of the issuing of the C18 Notice.

100. Further correspondence was exchanged, and the review listed the material seen including BTI … 9716, “… for goods of the type being imported by QHH and the subject of this review. The BTI was not issued to QHH and expired on 16 December 2016.” It also listed, “12 September 2019 - Letter sent to QHH proposing a visit by HMRC officers to check Customs and International trade records.” The final document was, “16 November 2020 - Letter from James Hickling, emailed to review officer … setting out the reasons why QHH believe the debt in this case should be calculated from March 2019 rather than 31 August 2018.” In that final document, on IDD headed notepaper, Mr Hickling accepted that the classification code 7616 9990 99 was now correct. Thus, the classification ground was not only not raised, but at that stage, the change in code was accepted to be correct (save as to timing). No reference to the procedural ground was made at all.

101. The independent review concluded that 7616 9990 99 was the correct customs classification and that this came into force on the day immediately after the CNEN was issued, here 30 August 2018.

102. On 29 June 2021, in a letter on QHH notepaper, QHH wrote, under the heading, “Quantum House Holdings Limited - Review Conclusion Letter Appeal to First Tier Tribunal,” “I can confirm that to date Quantum House Holdings Limited has not paid any of the amounts demanded by the C18.”

103. At no point in any correspondence to HMRC, to Officer Katib or in the independent review process did QHH once state that IDD should be the correct addressee as the person who should be liable for any customs debt either before or after the issuance of the C18 until the notice of appeal was lodged with the Tribunal.

104. Because of the conclusions of the independent review, QHH remained aggrieved and appealed to the Tribunal. Technically, the appeal was late, but HMRC confirmed to us at the beginning of the hearing that they had no objection to it proceeding.

The law

105. As we have said, we will deal with the classification ground first, the timing ground second and the procedural ground third. The procedural ground involves consideration of EU legislation as well as the principles of estoppel by convention which we have separated out as it is only if QHH is not liable for the customs debt by application of the relevant principles on the facts that estoppel by convention will require consideration.

106. We are grateful to the Advocates on both sides for their written materials and oral submissions. We will be forgiven for not setting out the submissions on the law which were extensive and wide-ranging but all of which we have considered.

(i) The classification ground - what are the principles that apply to categorising an RBS?

107. In the end, upon this issue, there was not a vast chasm between the parties as to the principles (as opposed to their application to the facts).

I. The Union Customs Code (‘UCC’)

108. Article 1 (1) of the Union Customs Code (Council Regulation (EU) No. 952/2013) (‘UCC’) under the heading Subject matter and scope states:

“1. This Regulation establishes the Union Customs Code (the Code), laying down the general rules and procedures applicable to goods brought into or taken out of the customs territory of the Union”.

109. The primacy of the UCC as applied by Regulation (EU) 2015/2446 (‘the Delegated Act’) and Regulation (EU) 2015/2447 (‘the Implementing Act’) governing imports after 1 May 2016 is not in dispute.

110. Article 56 is located within chapter 1 of Title 2 of the UCC and is headed Common Customs Tariff and Surveillance. So far as material Article 56 states:

“1. Import and export duty due shall be based on the Common Customs Tariff.

Other measures prescribed by Union provisions governing specific fields relating to trade in goods shall, where appropriate, be applied in accordance with the tariff classification of those goods.

2. The Common Customs Tariff shall comprise all of the following:

(a) the Combined Nomenclature of goods as laid down in Regulation (EEC) No 2658/87;

(b) any other nomenclature which is wholly or partly based on the Combined Nomenclature or which provides for further subdivisions to it, and which is established by Union provisions governing specific fields with a view to the application of tariff measures relating to trade in goods;

(c) the conventional or normal autonomous customs duty applicable to goods covered by the Combined Nomenclature;

(d) the preferential tariff measures contained in agreements which the Union has concluded with certain countries or territories outside the customs territory of the Union or groups of such countries or territories;

(e) preferential tariff measures adopted unilaterally by the Union in respect of certain countries or territories outside the customs territory of the Union or groups of such countries or territories;

(f) autonomous measures providing for a reduction in, or exemption from, customs duty on certain goods;

(g) favourable tariff treatment specified for certain goods, by reason of their nature or end-use, in the framework of measures referred to under points (c) to (f) or (h);

(h) other tariff measures provided for by agricultural or commercial or other Union legislation.

…”

111. Article 57 is headed Tariff classification of goods. That states:

“1. For the application of the Common Customs Tariff, tariff classification of goods shall consist in the determination of one of the subheadings or further subdivisions of the Combined Nomenclature under which those goods are to be classified.

2. For the application of non-tariff measures, tariff classification of goods shall consist in the determination of one of the subheadings or further subdivisions of the Combined Nomenclature, or of any other nomenclature which is established by Union provisions and which is wholly or partly based on the Combined Nomenclature or which provides for further subdivisions to it, under which those goods are to be classified.

3. The subheading or further subdivision determined in accordance with paragraphs 1 and 2 shall be used for the purpose of applying the measures linked to that subheading.

4. The Commission may adopt measures to determine the tariff classification of goods in accordance with paragraphs 1 and 2”.

II. The Common Customs Tariff (‘CCT’)

112. It will be seen from those Articles that the Common Customs Tariff (‘CCT’) controls the classification of goods imported into the EU. For our purposes the focus is upon paragraph 2(a) of Article 56 and “the Combined Nomenclature of goods as laid down in Regulation (EEC) No 2658/87” (‘CN Regulation’).

113. The Combined Nomenclature of goods (‘CN’) is produced as an annex to the CN Regulation. The CN enables a systematic classification of goods. Each good should be classified once in a single place.

114. The CN is reproduced in the UK Tariff by regulation (and amended annually).

115. In Vtech Electronics Limited v HMRC [2003] EWHC 59 (Ch) (‘Vtech’) the High Court considered an appeal by the taxpayer against the classification of its products as “toys” rather than “games”. The difference in duty was significant, with that for “games” being considerably less. Lawrence Collins J (as he then was) set out the legal background of the CCT:

“[6] The Common Customs Tariff came into existence in 1968. By art 28 of the revised EC Treaty Common Customs Tariff duties are fixed by the Council acting on a qualified majority on a proposal from the Commission.

[7] The level of customs duties on goods imported from outside the EC is determined at Community level on the basis of the Combined Nomenclature (“CN”) established by art 1 of Council reg 2658/1987. The CN is established on the basis of the World Customs Organisation's Harmonised System laid down in the International Convention on the Harmonised Commodity Description and Coding System 1983 to which the Community is a party.

[8] Article 3(1)(a)(ii) of the International Convention provides that, subject to certain exceptions, each contracting party undertakes “to apply the General Rules for the interpretation of the Harmonised System and all the Section, Chapter and Subheading Notes and shall not modify the scope of the Section, Chapters, headings or subheadings of the Harmonised System”. The International Convention is kept up to date by the Harmonized System Committee, which is composed of representatives of the contracting states.

[9] The CN, originally in Annex I to reg 2658/87, is re-issued annually: the version applicable to the present case is Annex I to reg 2204/99 (12.10.99 OJ L278). The CN comprises: (a) the nomenclature of the harmonized system provided for by the International Convention; (b) Community subdivisions to that nomenclature (“CN subheadings”); and (c) preliminary provisions, additional section or chapter notes and footnotes relating to CN subheadings.

[10] The CN uses an eight-digit numerical system to identify a product, the first six digits of which are those of the harmonised system, and the two extra digits identify the CN sub-headings of which there are about 10,000. Where there is no Community sub-heading these two digits are “00” and there are also ninth and tenth digits which identify the Community (TARIC) subheadings of which there are about 18,000.

[11] There are Explanatory Notes to the Nomenclature of the Customs Co-operation Council, otherwise known as Explanatory Notes to the Harmonised System (“HSENs”). The Community has also adopted Explanatory Notes to the CN (pursuant to art 9(1)(a) of Council reg 2658/87), known as CNENs.

[12] Binding Tariff Information is issued by the customs authorities of the Member States pursuant to art 12 of the Common Customs Code (Council reg 2913/92/EEC) on request from a trader. They are called “BTIs”, and such information is binding on the authorities in respect of the tariff classification of goods. The BTIs issued in this matter were the subject of the appeal to the Tribunal in the present case.”

III. The approach to classification under the CCT

116. In Vtech, Lawrence Collins J continued with a section headed ‘Interpretation’ at [13] - [17]. In material part he said:

“[13] There are many decisions of the European Court on the interpretation of the tariff headings. The decisive criterion for the tariff classification of goods must be sought generally, regard being had to the requirements of legal certainty, in their objective characteristics and properties, as defined in the headings of the Common Customs Tariff: eg Case C- 177/91 BioforceGmbH v Oberfinananzdirektion Munchen [1993] ECR I-45, where the function of the product (hawthorn drops) was decisive; Case C-309/98 Holz Geenen GmbH v Oberfinananzdirektion Munchen [2000] ECR I-1975, where the intended use of the product (wood blocks for window frames) was said to be such an objective criterion if it was inherent in the product; Case C-338/95 Wiener SI GmbH v Hauptzollamt Emmerich [1997] ECR I-6495, where the intended use of the product (pyjamas) was decisive, and the presentation of the goods was regarded as relevant.

[14] The headings and the Explanatory Notes do not have legally binding force and cannot prevail over the provisions of the Common Customs Tariff: Case C-35/93 Develop Dr Eisbein GmbH & Co. v Hauptzollamt Stuttgart-West [1994] ECR I-2655, para 21; Case C-338/95 Wiener SI GmbH v Hauptzollamt Emmerich [1997] ECR I-6495, per Advocate General Jacobs, para 32; Case C-309/98 Holz Geenen Oberfinananzdirektion Munchen [2000] ECR I-1975, para 14. But they are important means for ensuring the uniform application of the Common Customs Tariff and are therefore useful aids to interpretation: eg Case C-338/95 Wiener SI GmbH v Hauptzollamt Emmerich [2000] ECR I-1975, para 11; Case C-309/98 Holz Geenen Oberfinananzdirektion Munchen [2000] ECR I-1975, para 14. They may show that a classification by Commission Regulation is invalid, if the error made by the Commission is manifest: eg Case C-463/98 Cabletron Systems Ltd v Revenue Commissioners [2001] ECR I-3495, para 22.

[15] It is for the national court (even in a case which has been referred to the European Court for guidance on the applicable principles) to determine the objective characteristics of a given product, having regard to a number of factors including their physical appearance, composition and presentation: Case C-338/95 Wiener SI GmbH v Hauptzollamt Emmerich [1997] ECR I-6495, para 21.

117. At [16] in material part he said:

“The General Rules for the Interpretation of the CN (“GIRs”) are contained in s 1A of Pt 1 of Annex 1 to Council reg 2658/87 and have the force of law …”

118. In that case it was not necessary to set out the six rules but here we must do so. The six GIRs are:

“Rule 1

The titles of sections, chapters and sub-chapters are provided for ease of reference only; for legal purposes, classification shall be determined according to the terms of the headings and any relative section or chapter notes and, provided such headings or notes do not otherwise require, according to the following provisions.

Rule 2

(a) Any reference in a heading to an article shall be taken to include a reference to that article incomplete or unfinished, provided that, as presented, the incomplete or unfinished article has the essential character of the complete or finished article. It shall also be taken to include a reference to that article complete or finished (or falling to be classified as complete or finished by virtue of this rule), presented unassembled or disassembled.

(b) Any reference in a heading to a material or substance shall be taken to include a reference to mixtures or combinations of that material or substance with other materials or substances. Any reference to goods of a given material or substance shall be taken to include a reference to goods consisting wholly or partly of such material or substance. The classification of goods consisting of more than one material or substance shall be according to the principles of rule.

Rule 3

When, by application of rule 2(b) or for any other reason, goods are prima facie classifiable under two or more headings, classification shall be effected as follows:

(a) the heading which provides the most specific description shall be preferred to headings providing a more general description. However, when two or more headings each refer to part only of the materials or substances contained in mixed or composite goods or to part only of the items in a set put up for retail sale, those headings are to be regarded as equally specific in relation to those goods, even if one of them gives a more complete or precise description of the goods;

(b) mixtures, composite goods consisting of different materials or made up of different components, and goods put up in sets for retail sale, which cannot be classified by reference to 3(a), shall be classified as if they consisted of the material or component which gives them their essential character, in so far as this criterion is applicable;

(c) when goods cannot be classified by reference to 3(a) or (b), they shall be classified under the heading which occurs last in numerical order among those which equally merit consideration.

Rule 4

Goods which cannot be classified in accordance with the above rules shall be classified under the heading appropriate to the goods to which they are most akin.

Rule 5

In addition to the foregoing provisions, the following rules shall apply in respect of the goods referred to therein:

(a) camera cases, musical instrument cases, gun cases, drawing-instrument cases, necklace cases and similar containers, specially shaped or fitted to contain a specific article or set of articles, suitable for long-term use and presented with the articles for which they are intended, shall be classified with such articles when of a kind normally sold therewith. This rule does not, however, apply to containers which give the whole its essential character;

(b) subject to the provisions of rule 5(a), packing materials and packing containers presented with the goods therein shall be classified with the goods if they are of a kind normally used for packing such goods. However, this provision is not binding when such packing materials or packing containers are clearly suitable for repetitive use.

Rule 6

For legal purposes, the classification of goods in the subheadings of a heading shall be determined according to the terms of those subheadings and any related subheading notes and, mutatis mutandis, to the above rules, on the understanding that only subheadings at the same level are comparable. For the purposes of this rule, the relative section and chapter notes also apply, unless the context requires otherwise.”

119. In Joined Cases C-288/09 and C-289/09, British Sky Broadcasting Group Plc and Pace PLC (‘BSkyB’) the CJEU appears to have gone slightly further than Lawrence Collins J on the question of conflict between the CN on the one hand and a CNEN on the other. It said:

“65 Accordingly, where it is apparent that they are contrary to the wording of the headings of the CN and the section or chapter notes, the Explanatory Notes to the CN must be disregarded (see Case C-229/06 Sunshine Deutschland Handelsgesellschaft [2007] ECR I-3251, paragraph 31; Case C‑312/07 JVC France [2008] ECR I-4165, paragraph 34; and Kamino International Logistics, paragraphs 49 and 50).”

120. Whipple LJ, in the Court of Appeal, recently summarised the approach to be taken when considering the classification of goods in Build-A-Bear Workshop UK Holdings Limited v HMRC [2022] EWCA Civ 825 (‘Build-A-Bear’) at [15]:

“(1) The GIRs provide a set of rules for interpretation of the CN in order to ensure that all products are classified under the correct code and (unlike the HSENs and CNENs) all have “the force of law” (Vtech [16]).

(2) It is common ground that, in the interests of legal certainty and ease of verification, the decisive criteria for the tariff classification of goods must be sought in their objective characteristics and properties as defined by the wording of the relevant heading of the CN and of the notes to the sections or chapters of the CN (Holz Geenen GmBH v Oberfinanzdirektion Munchen (Case C-309/98) at [14]).

(3) The intended use of the goods may be considered as part of the classification analysis where that use is inherent to the goods and that inherent characteristics capable of being assessed by reference to the objective characteristics and properties of the goods (see Hauptzollant Hamburg-St. Annen v Thyssen Haniel Logistic GmbH (Case C-459/93) (“Thyssen Haniel”) at [13]).

(4) Having regard to the objective characteristics and properties of the goods, a combined examination of the wording of the headings and explanatory notes to the relevant sections and chapters should be undertaken to determine whether a definitive classification can be reached, in accordance with GIR1 and GIR 6. If not, then in order to resolve the conflict between the competing provisions, recourse must be had to GIRs 2-5 (see the opinion of Advocate General Kokott in Uroplasty v Inspector v Belastingdienst (Case C-514/04) (“Uroplasty”) at [42].

(5) GIR 3 will only apply when it is apparent that goods are prima facie classifiable under a number of headings (see Kip Europe SA & Ors and Hewlett Packard International SARL v Administration de douanes (Cases C-362/07-C363/07) (“Kip Europe”) at [39] and the wording of GIR 3 itself).

(6) Classification must proceed on a strictly hierarchical basis, taking each level of the CN in turn. The wording of headings and subheadings can be compared only with the wording of headings and subheadings at the same level (see the opinion of Advocate General Kokott, Uroplasty [43]).

(7) The HSENs and CNENs are an important aid to the interpretation of the scope of the HSENs and the CNENs must therefore be compatible with the provisions of the CN, and cannot alter the meaning of those provisions (see Revenue and Customs Commissioners v Honeywell Analytics Limited [2018] EWCA Civ 579 per Davis LJ (“Honeywell Analytics”) at [95] and Invamed per Patten LJ at [12]).”

121. The expression of the law at (4) is consistent with HMRC v Flir Systems AB [2009] EWCH 82 (Ch.) (‘Flir’) per Henderson J (as he then was) at [14]. That at (7) is consistent with the Supreme Court’s decision in Amoena v HMRC [2016] UKSC and the decision of the CJEU in Develop Dr Eisbein GmbH & Co v Hamptzollant Stuggardt-West (Case C-35/93).

122. Finally, in HMRC v International Plywood (Importers) Limited [2023] UKUT 278 (TCC) (‘Plywood’) the Upper Tribunal expressed itself as follows:

“The Law

Customs Legislation, Union Customs Code,

13. The Union Customs Code (‘UCC’) was established by EU Regulation 952/2013 to increase consistency on customs. The CN, laid down in Regulation 2658/87, is the legal basis for the tariff. The CN is amended annually and reproduced in the UK Tariff. The CN, which is directly applicable in all Member States, sets out the tariff subheadings and subdivisions for the classification of goods.

14. The six General Rules of Interpretation (“GIRs”), contained in Part 1, Section 1 of the CN, set out the principles by which the CN must be interpreted. We return to the GIRs below.

15. The CN is based on the international Harmonised Commodity and Coding System (“Harmonised System” or “HS”) established by the World Customs Organisation (“WCO”).

16. The Explanatory Notes to the Harmonised System (“HSENs”) published by the WCO are not legally binding but are highly persuasive in determining the proper classification. There are also Explanatory Notes to the CN (“CNENs”) which refer to the HSENs.

Principles of interpretation and GIRs

17. The FTT accurately summarised the principles to be applied in classification appeals in its decision at [8]:

‘At [2-17] of MSA Britain Ltd v HMRC [2019] UKFTT 693 (TC) and [6-10] of Orlight Ltd v HMRC [2013] UKFTT 732 (TC), the Tribunal helpfully summarised the law and approach to interpretation in classification appeals, as follows:

(a) Annex 1 of Regulation 2658/87 contains a combined nomenclature (“the CN”) which classifies goods using an eight-digit identification system. The first two digits represent the chapter heading, the next two digits represent headings in the chapter, the fifth and sixth digits represent subheadings (which mirror those used in the WTO’s nomenclature) and the final two digits represent the EU’s further subdivisions.

(b) Annex 1 also contains six general rules for the interpretation of the CN (“the GIRs”).

…

(c) “...the decisive criteria for the classification of goods...is in general to be found in their objective characteristics and properties as defined in the wording of the relevant CN and of the notes to the sections or chapters...the intended use of a product may constitute an objective criterion in relation to a tariff classification if it is inherent in the product, and such inherent character must be capable of being assessed on the basis of the product’s objective characteristics and properties...” (Intermodal Transports BV Case C-495/03);

(d) There are explanatory notes to the W[C]O’s nomenclature, Harmonised System Explanatory Notes (“HSENs”) and explanatory notes produced by the European Commission, Combined Nomenclature Explanatory Notes (“CNENs”). Neither have force of law but both may be important aids to interpretation;

(e) Where the EU commission has promulgated a classification regulation in relation to particular goods:

(i) the scope of that regulation must be determined by taking into account, inter alia, the reasons given in the regulation (Hewlett-Packard Case C-199/00);

(ii) A classification regulation can assist in classification of similar products by analogy.”

123. The Upper Tribunal in Plywood was considering the decision of the Tribunal in the same case, the hearing of which was only two days after the Court of Appeal handed down its decision in Build-A-Bear. The Upper Tribunal cited Build-A-Bear at [109] for a limited purpose.

124. We must also mention another source of international law. We accept the submission of Avv. Rovetta that, although not directly enforceable, “where the [EU] has legislated in the field in question, the primacy of international agreements concluded by the [EU] over provisions of secondary [EU] legislation means that such provisions must, so far as is possible, be interpreted in a manner that is consistent with those agreements” (see, for example, Case C-428/08 Monsanto Technology (‘Monsanto’) at [72]).

125. Article X (3) (a) of GATT requires that customs authorities classify the goods in a uniform manner within the customs territory. In the report of the WTO adjudicating panel in Case DS-315 EC - Selected Customs Matters (‘SCM’) the conclusion and summary are relied upon by QHH where it was said:

“7.135 In summary, the interpretative material upon which the Panel is entitled to rely under the Vienna Convention in interpreting the term "uniform" in Article X:3(a) of the GATT 1994 indicates that that term covers, inter alia, geographic uniformity. In other words, administration should be uniform in different places within a particular WTO Member. Further, the Panel considers that the form, nature and scale of the alleged non-uniform administration and the laws, regulations, judicial decisions and rulings that are allegedly being administered in a non-uniform manner should be taken into consideration when interpreting the term "uniform" in Article X:3(a) of the GATT 1994 in the context of a particular case. The Panel considers that the narrower the challenge both in terms of the administration that is being challenged and the laws, regulations, decisions and rulings which are alleged to be administered in a non-uniform manner in a particular case, the more demanding the requirement of uniformity. The broader and more wide-ranging the challenge both in terms of the nature of administration that is being challenged and the specific laws, regulations, decisions and rulings or provisions thereof that are alleged to be administered in a non-uniform manner in a particular case, a less exacting standard of uniformity should be applied. The Panel also considers that the interpretation of the term "uniform" in Article X:3(a) of the GATT 1994 does not necessarily entail instantaneous uniformity. Rather, uniformity must be attained within a period of time that is reasonable. What is reasonable will depend upon the form, nature and scale of the administration at issue as well as the complexity of the factual and legal issues raised by the act of administration that is being challenged. It is the Panel's view that, in all cases, regardless of the form, nature and scope of administration at issue, administration should not fall below certain minimum standards of due process, which encompass notions such as notice, transparency, fairness and equity.”

126. However, this must be read in context of the Panel’s views on what “uniformity” requires within WTO members and the practical realities that exist. The Panel said:

“iii) Article X:3(a) GATT lays down minimum standards

4.211 In line with the foregoing, it must be considered that Article X:3(a) GATT only lays down minimum standards. It does not oblige WTO Members to meet the highest possible standard achievable at a given point in time. This character of Article X:3(a) as a minimum standard has been emphasized by the Appellate Body in US - Shrimp. The Panel in Argentina - Hides and Leather has also cautioned against reading too much into Article X:3(a) GATT.

4.212 Moreover, minor administrative differences in treatment cannot be regarded as implying a violation of Article X:3(a) GATT. This was clearly stated by the GATT Panel in EC - Dessert Apples, which confirmed that certain variations between EC member States in the administration of import licensing, e.g., as regards the form in which licence applications could be made and the requirement of pro-forma invoices, did not constitute a breach of Article X:3(a) GATT.

4.213 Overall, Article X:3(a) GATT is therefore a minimum standards provision which guarantees only a certain minimum level of uniformity in administration. Moreover, Article X:3(a) GATT does not prohibit administrative variations where such variations are minor or do not significantly affect the interests of traders.

(iv) The meaning of "uniform administration"

4.214 The meaning of the requirement of "uniform administration" must be established in the light of the foregoing observations. Moreover, account must be taken of the practical realities in which customs administrations must work.

4.215 The administration of customs laws in the real world involves a number of difficulties and challenges. First of all, the administration of customs frequently involves complex questions of law and fact. Second, the circumstances under which customs authorities operate are in continuous evolution due to changes in goods traded or commercial behaviour. This requires customs authorities to continuously adapt to new realities. Third, customs administration is a mass business.

4.216 Therefore, a measure of realism is required in the application of Article X:3(a) GATT. If customs authorities struggle with a complex new question of law and fact, this does not already mean that authorities in the member concerned administer customs law in a non-uniform manner. Similarly, if it takes a certain amount of time to come to an established practice on a new and complex issue of customs law, this does not yet mean that customs laws are being administered in a non-uniform way.

4.217 A complete uniformity in the application of customs laws could never be achieved by any Member, even those with the most efficient systems of customs administration. In a large country with a large bureaucracy, a minimum degree of non-uniformity is de facto unavoidable. This may occur, for instance, because a trader in a particular case does not challenge a particular decision even though it was illegal. In such a case, non-uniformity may be the result, but this does not mean that the Member in question fails to meet its obligations under Article X:3(a) GATT. The EC notes that the United States appears to agree with this, since it states that "the fact that divergences occur is not problematic in and of itself”.

4.218 The proposition that individual instances of administration are not probative for a violation of Article X:3(a) GATT also finds support in the case law under the DSU. In EC - Poultry, the Appellate Body already confirmed that individual measures of application do not fall within the scope of Article X GATT. In US - Hot Rolled Steel, the Panel stated that rather than relying on individual instances of administration, it was necessary for the complaining party to establish a pattern of decision making contrary to Article X:3(a) GATT.

4.219 Accordingly, whether a particular member meets the requirement of "uniformity" cannot be established merely by looking at an individual example of practice. Rather, uniformity can be assessed only on the basis of an overall pattern of customs administration. Only if, on the basis of such general patterns, a WTO Member's administration of its customs laws can be shown to be non-uniform, is the standard of Article X:3(a) GATT violated.

(b) The burden of proof

4.220 It is established case law under the DSU that the party which asserts a particular claim bears the burden of proof. In the present case, it is the United States which claims that the EC does not administer its customs laws in a uniform manner. It is accordingly the United States which must adduce evidence to establish a prima facie case that its claim is true. Only if the United States discharges this burden of proof will the burden shift to the EC to rebut the US case.

4.221 The United States does not even come close to discharging this burden of proof. In fact, the United States adduces only very sparse evidence regarding the actual administration of EC customs law. The examples given by the United States are partially irrelevant, partially inconclusive, and in any event do not show a general pattern of non-uniform administration of EC customs law.

…”

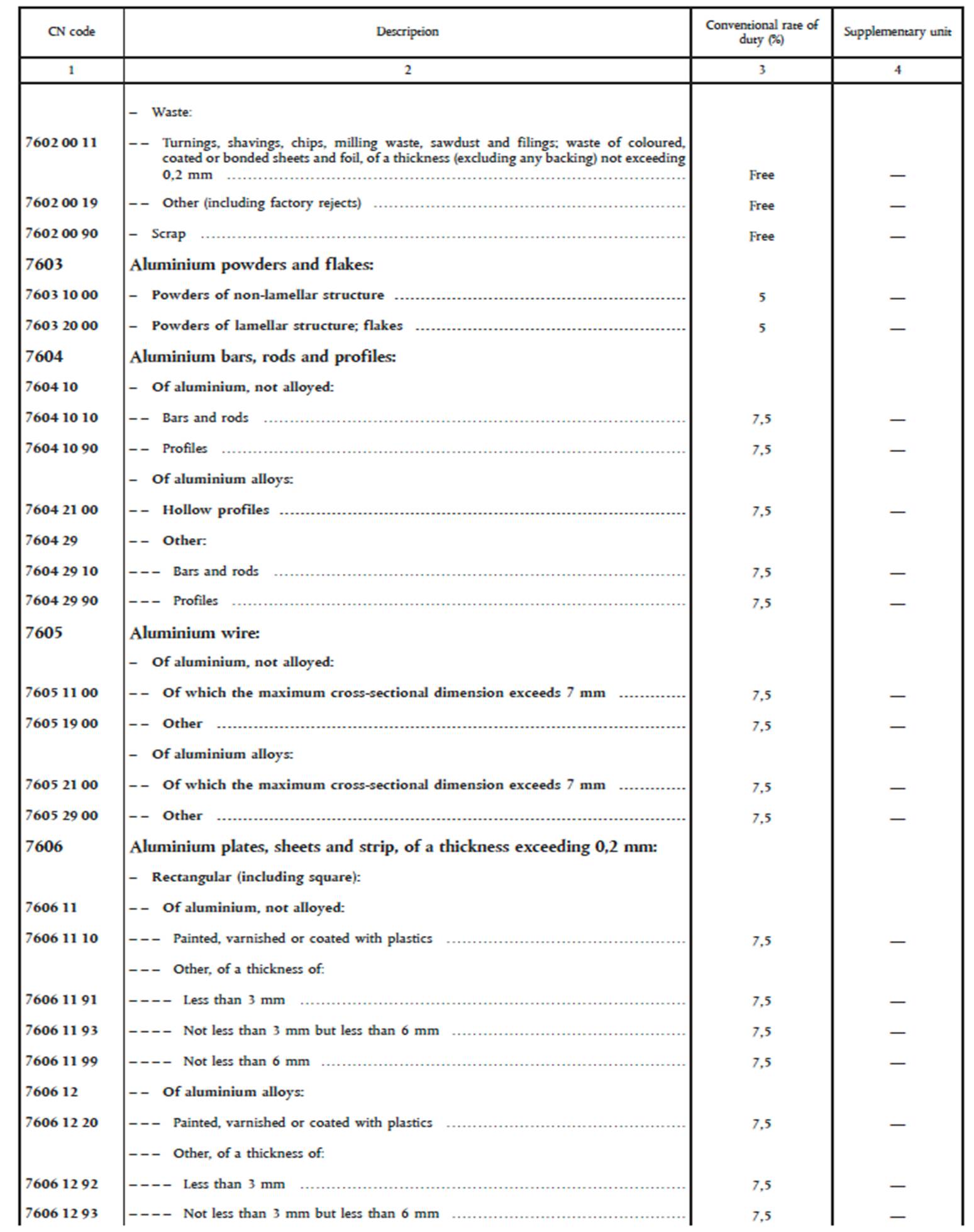

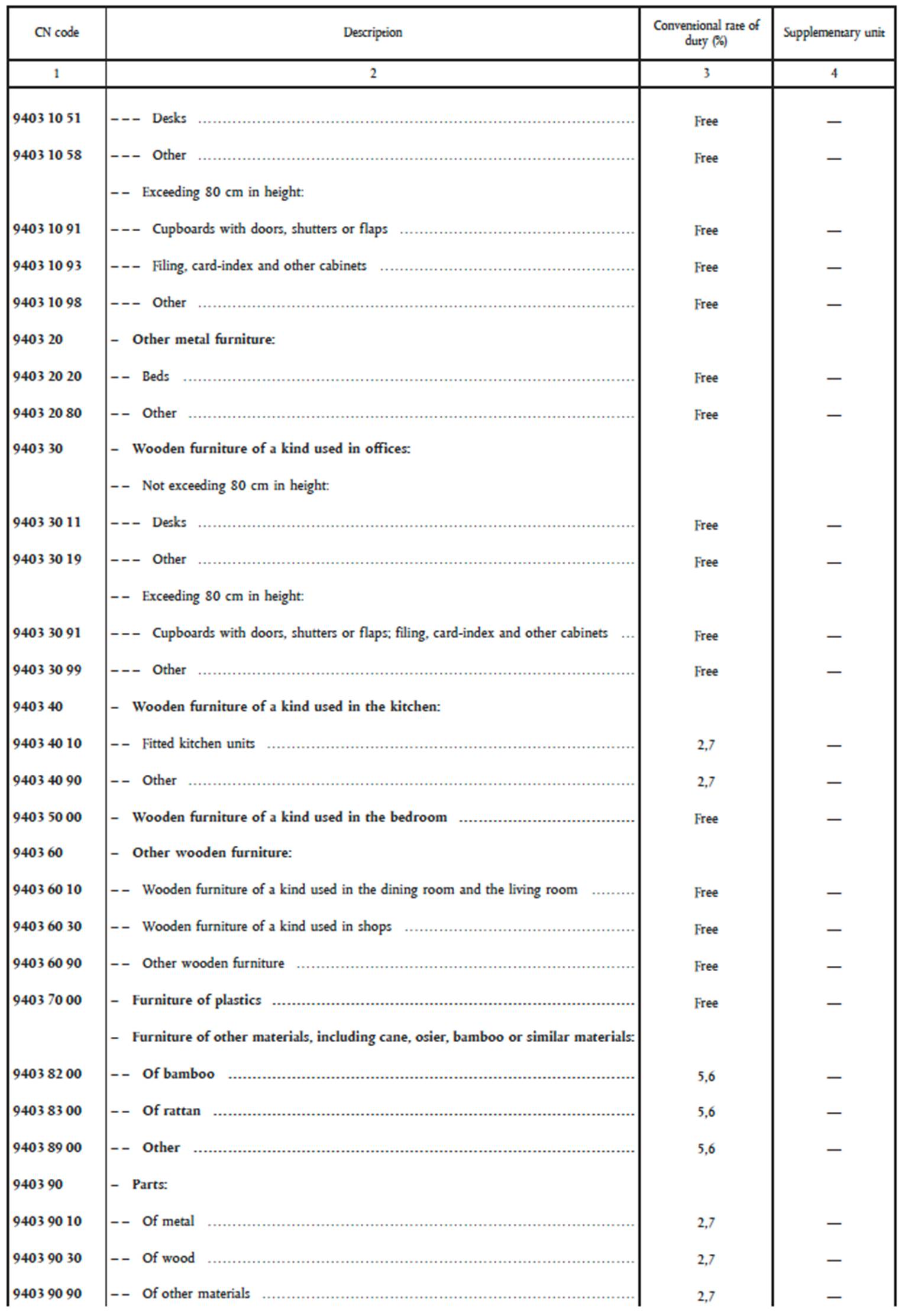

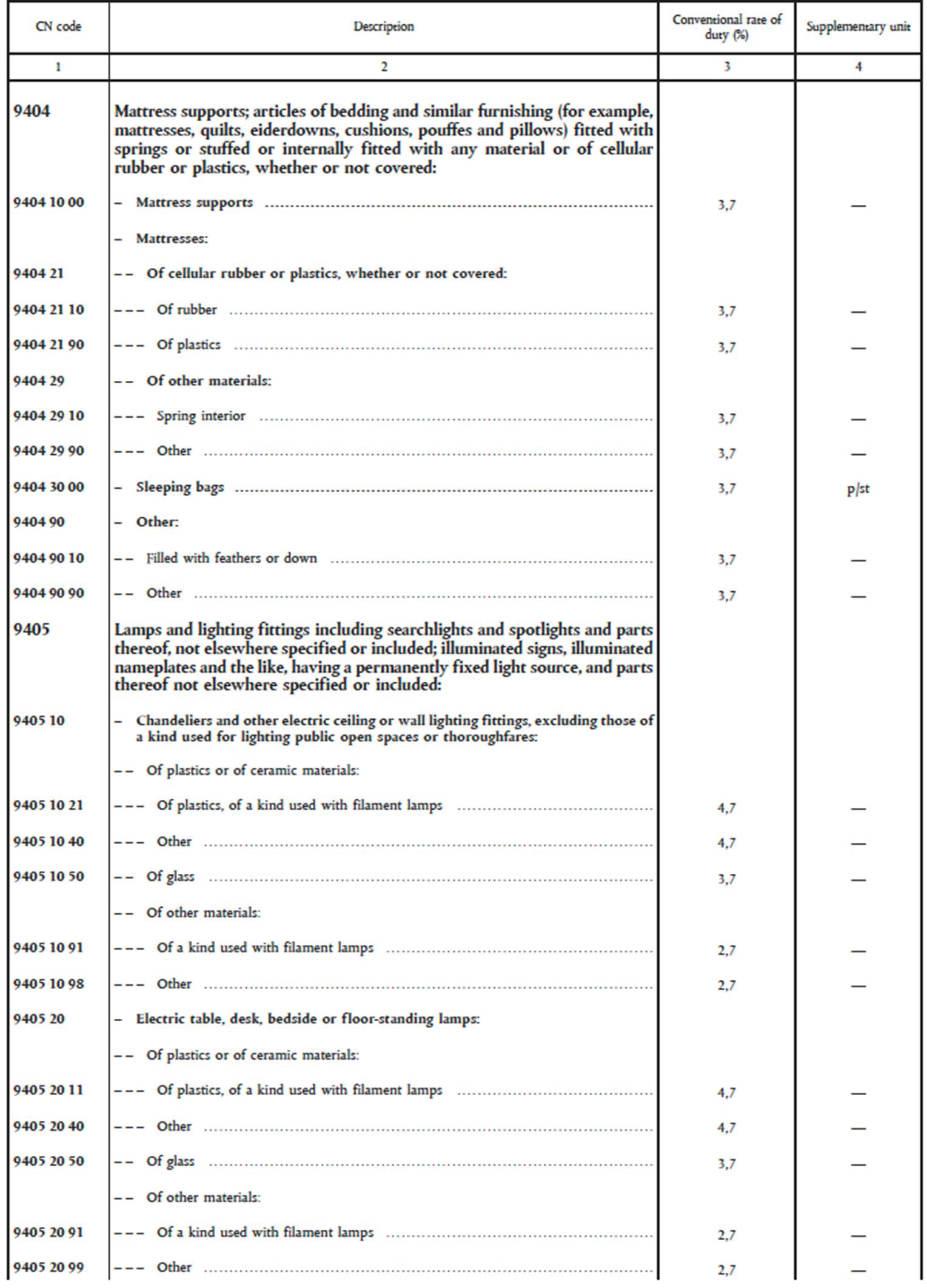

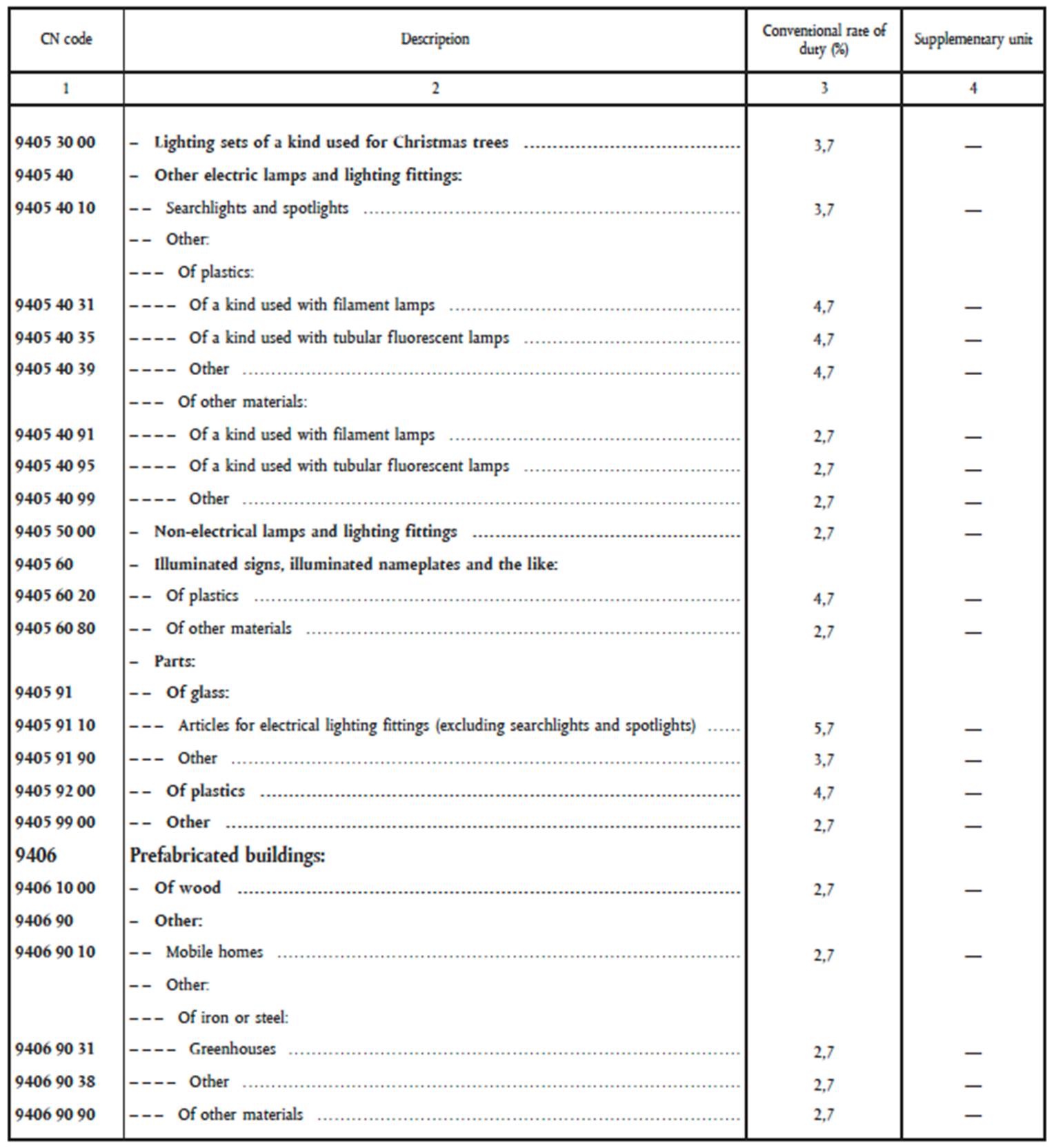

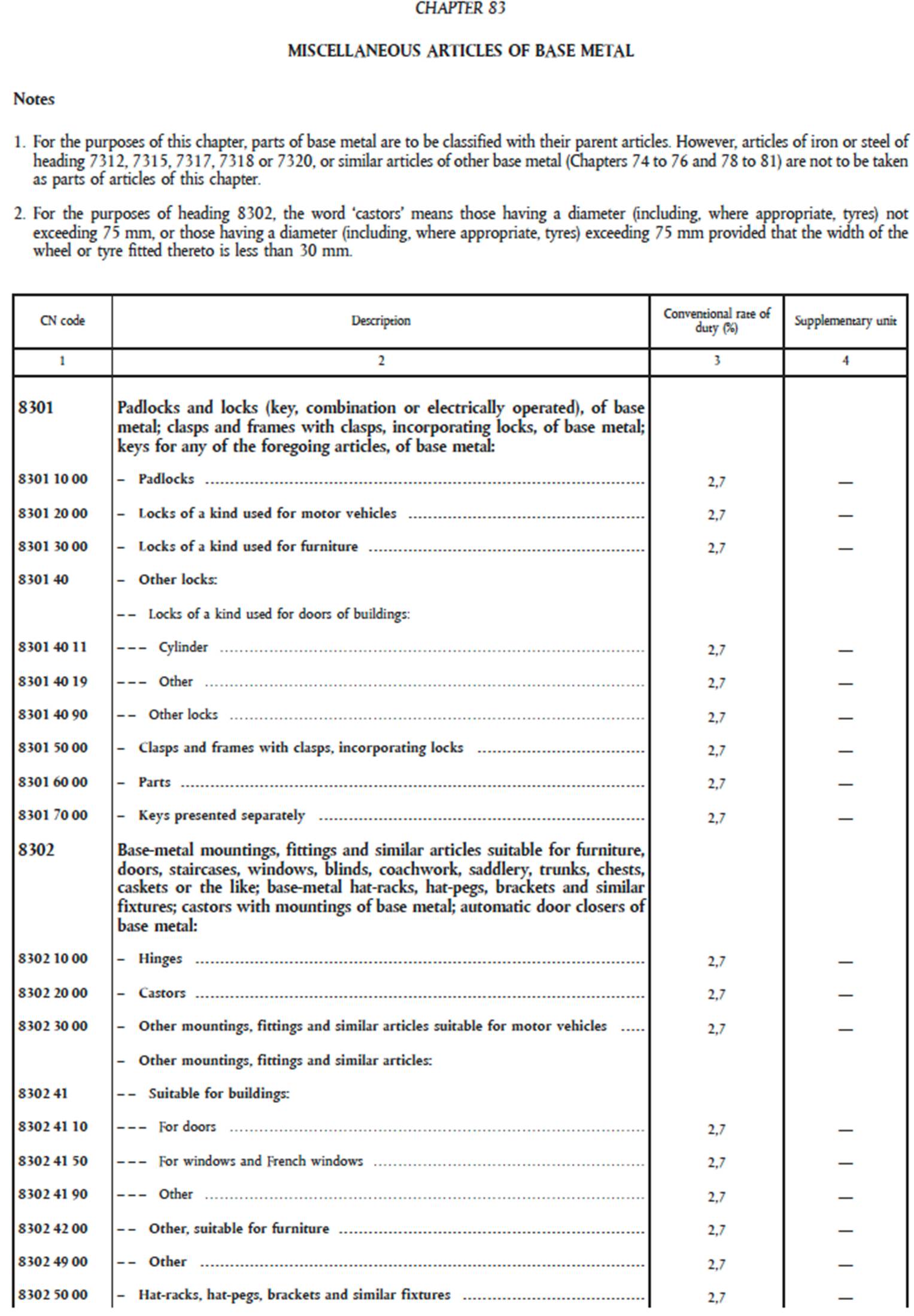

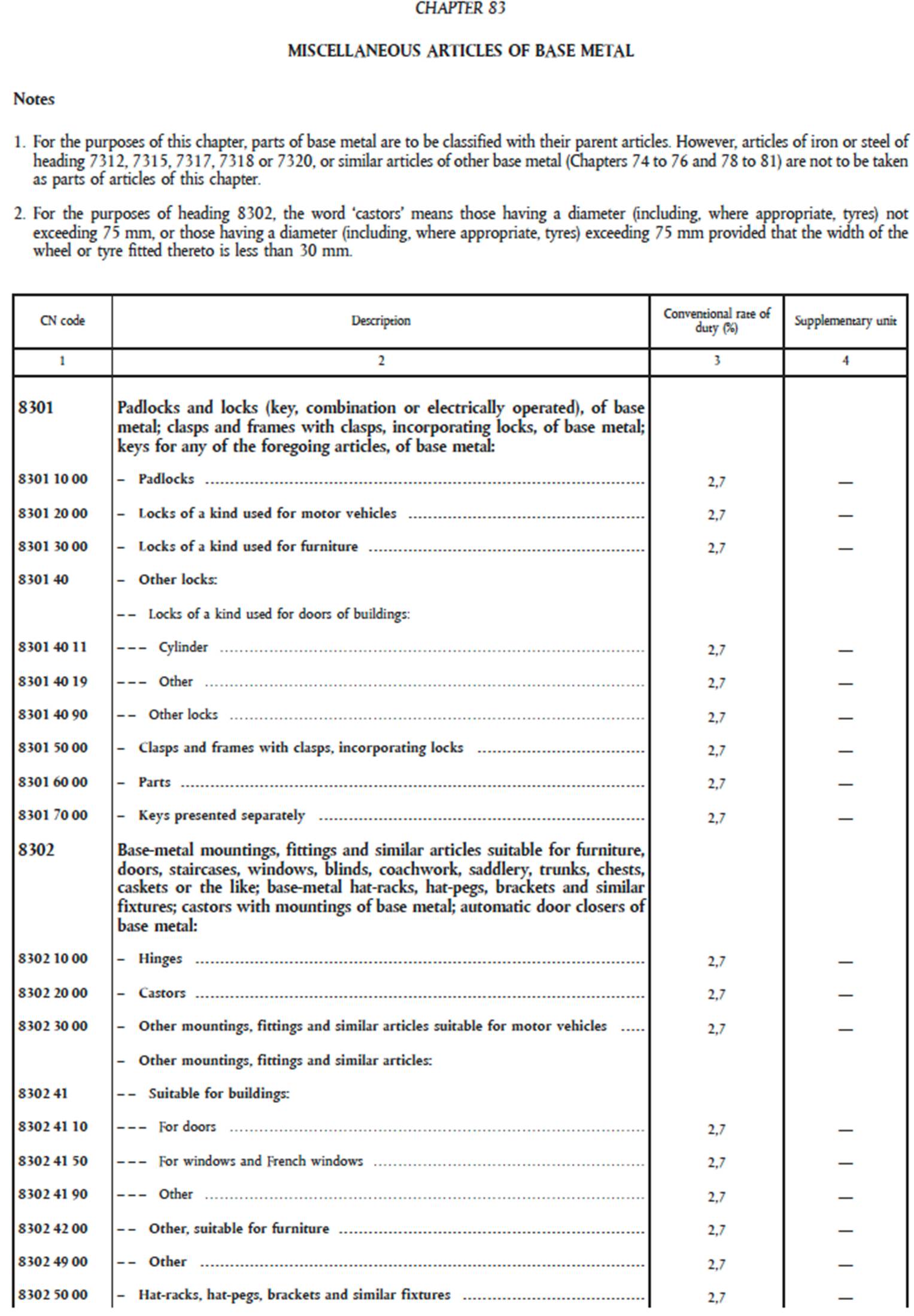

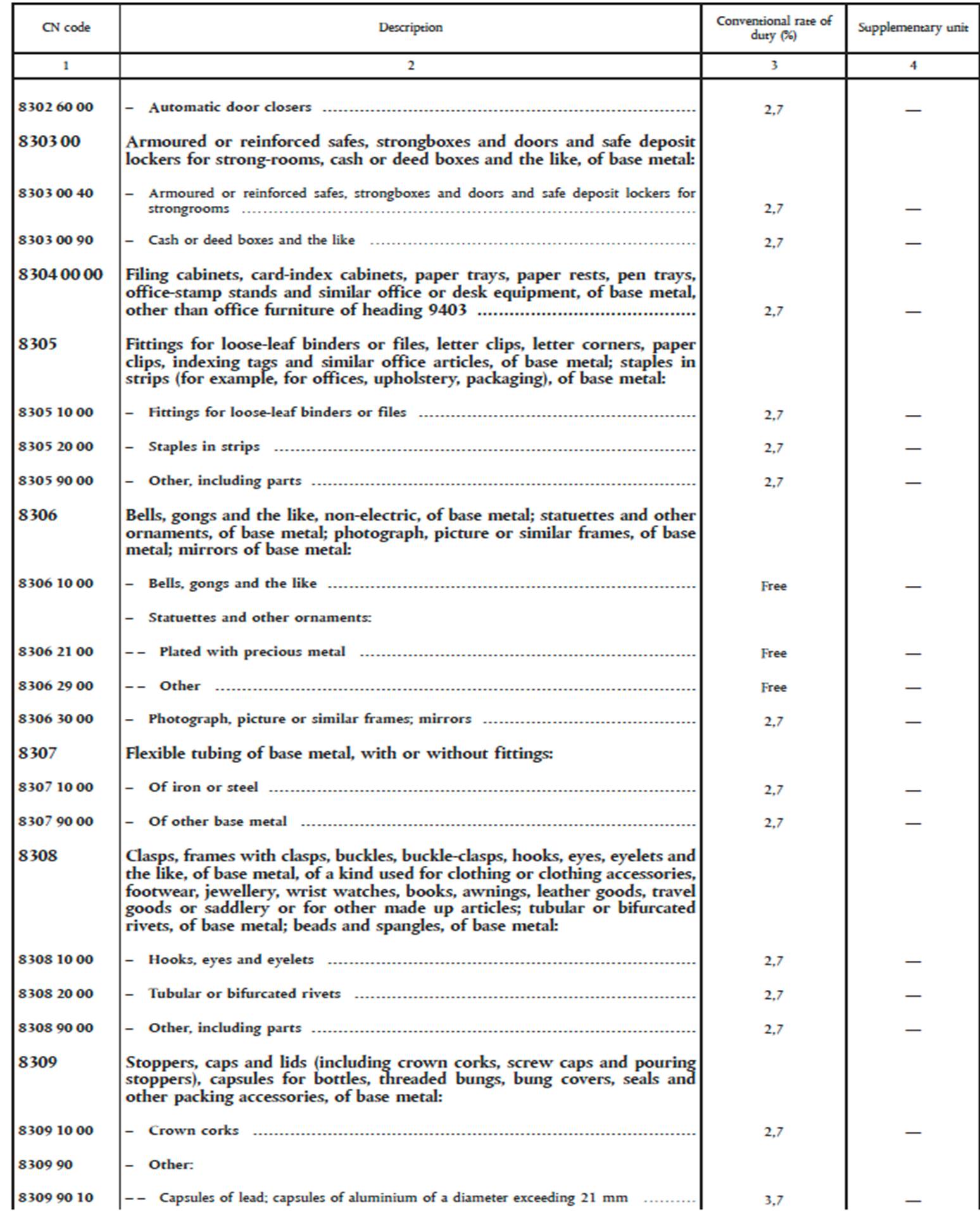

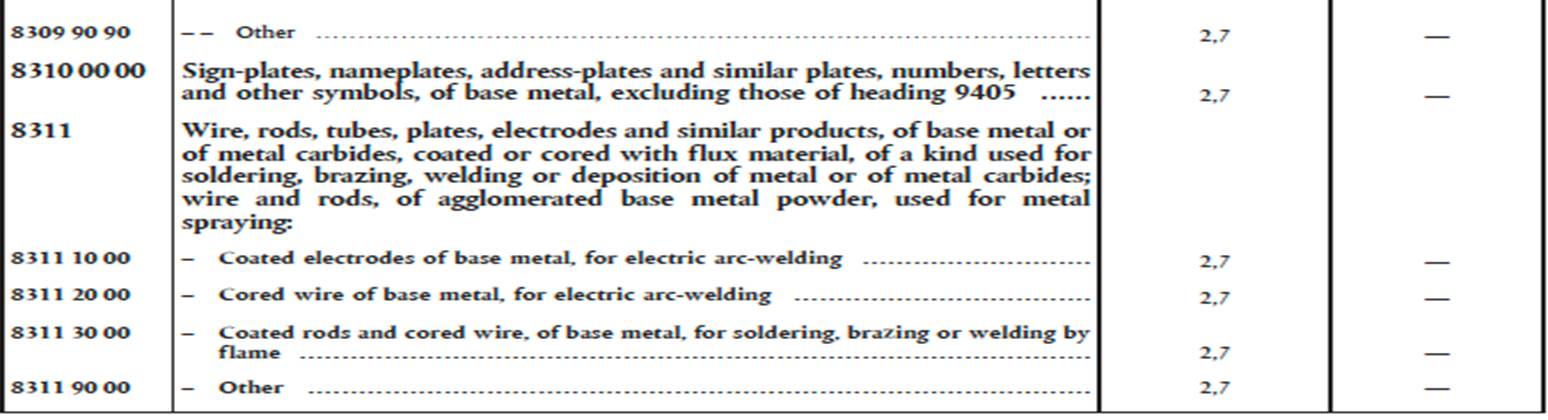

IV. The competing CNs

127. The meaning of the digits of a customs classification was explained by Lawrence Collins J in Vtech at [10] (see [115] above). Here there are three competing CN headings which we reproduce as Annexes to this decision .

128. However, central to the competing submissions was disagreement over the four digit heading rather than the sub-headings and digits. It is therefore upon those we focus.

(1) 9403 ‘Furniture’

129. QHH principally submit that the heading used prior to the CNEN of 30 August 2018 should continue to apply: namely 9403 found in Section XX (Miscellaneous Manufactured Articles) Chapter 94, because the essential characteristic of an RBS is one of being furniture.

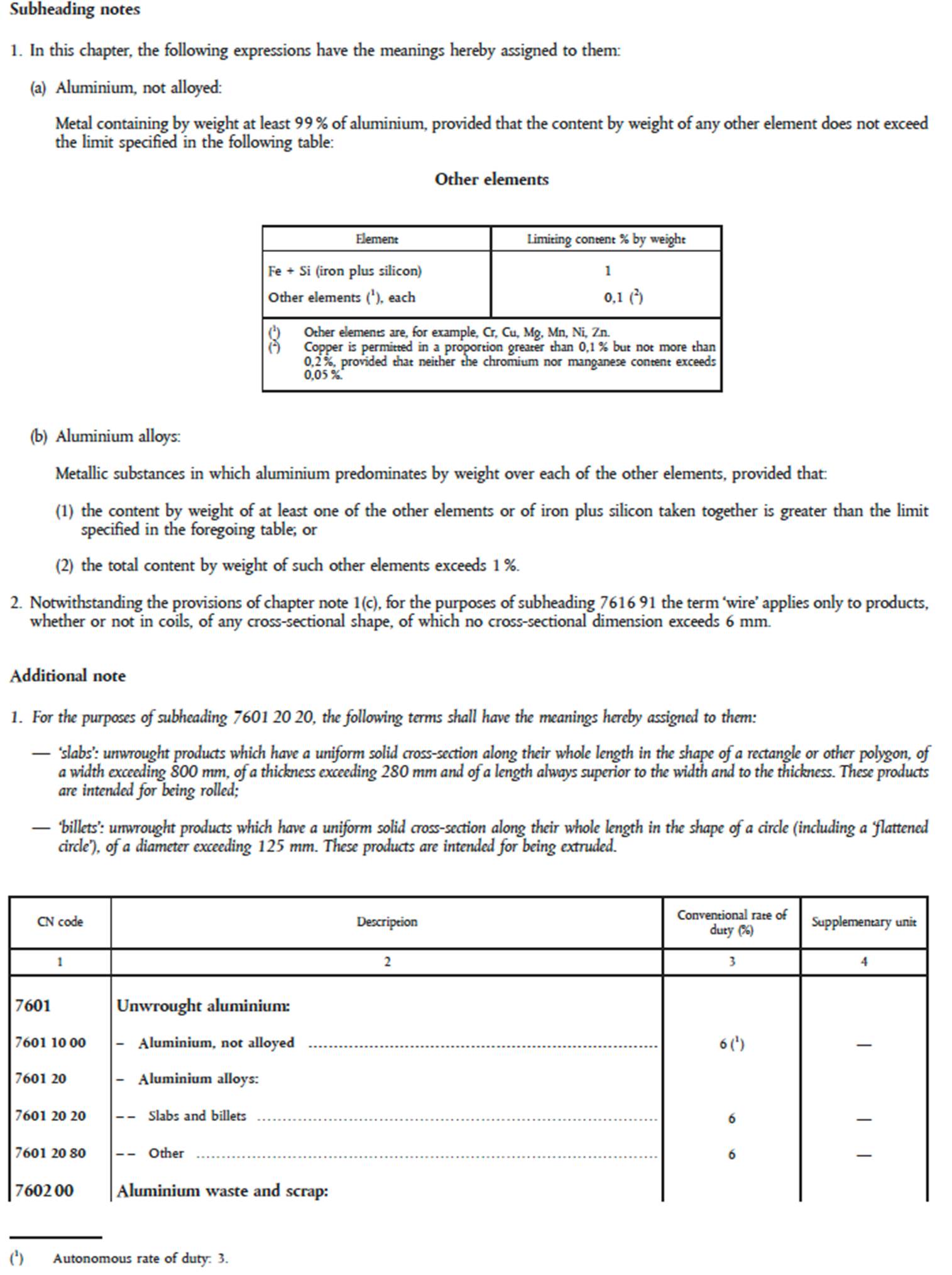

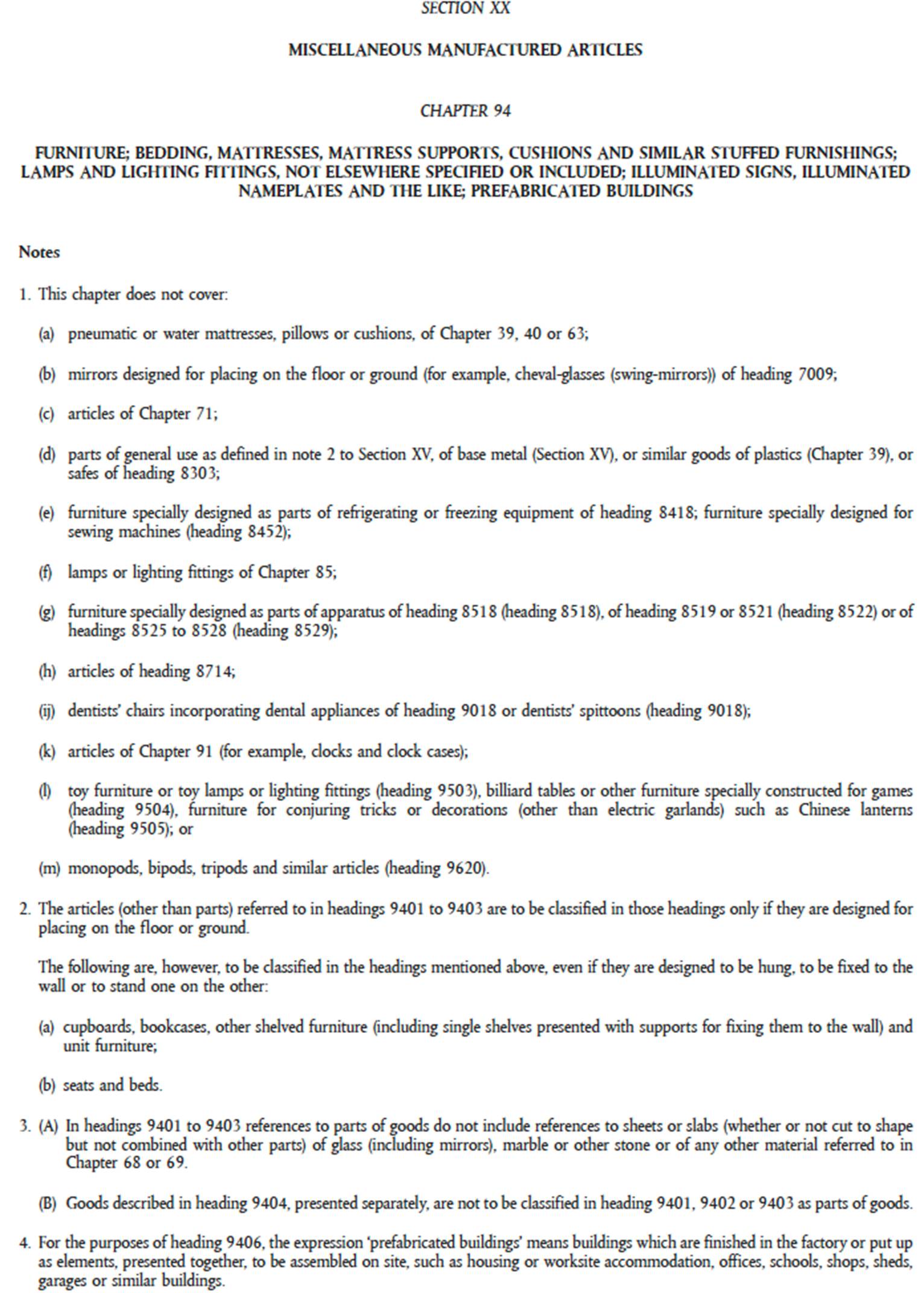

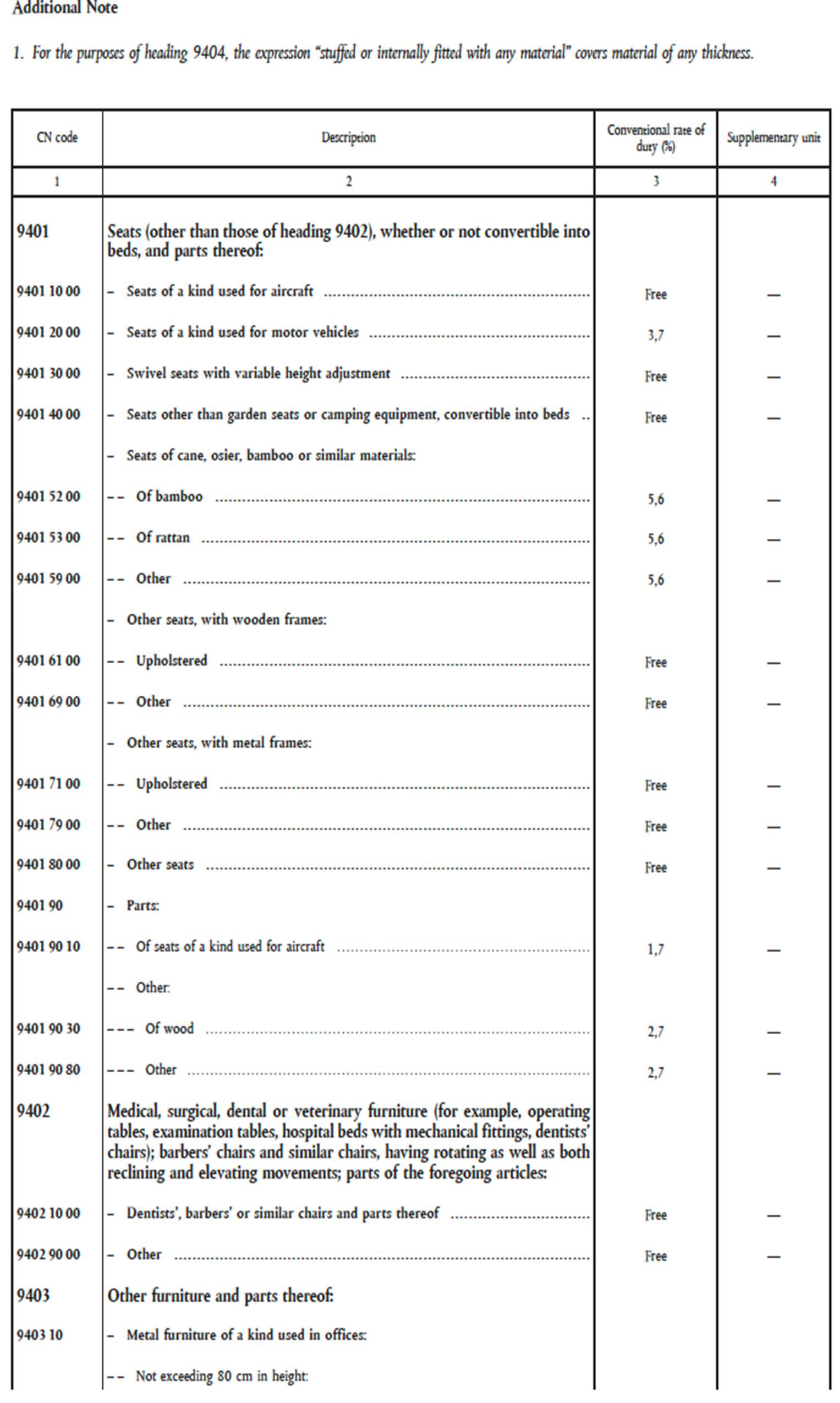

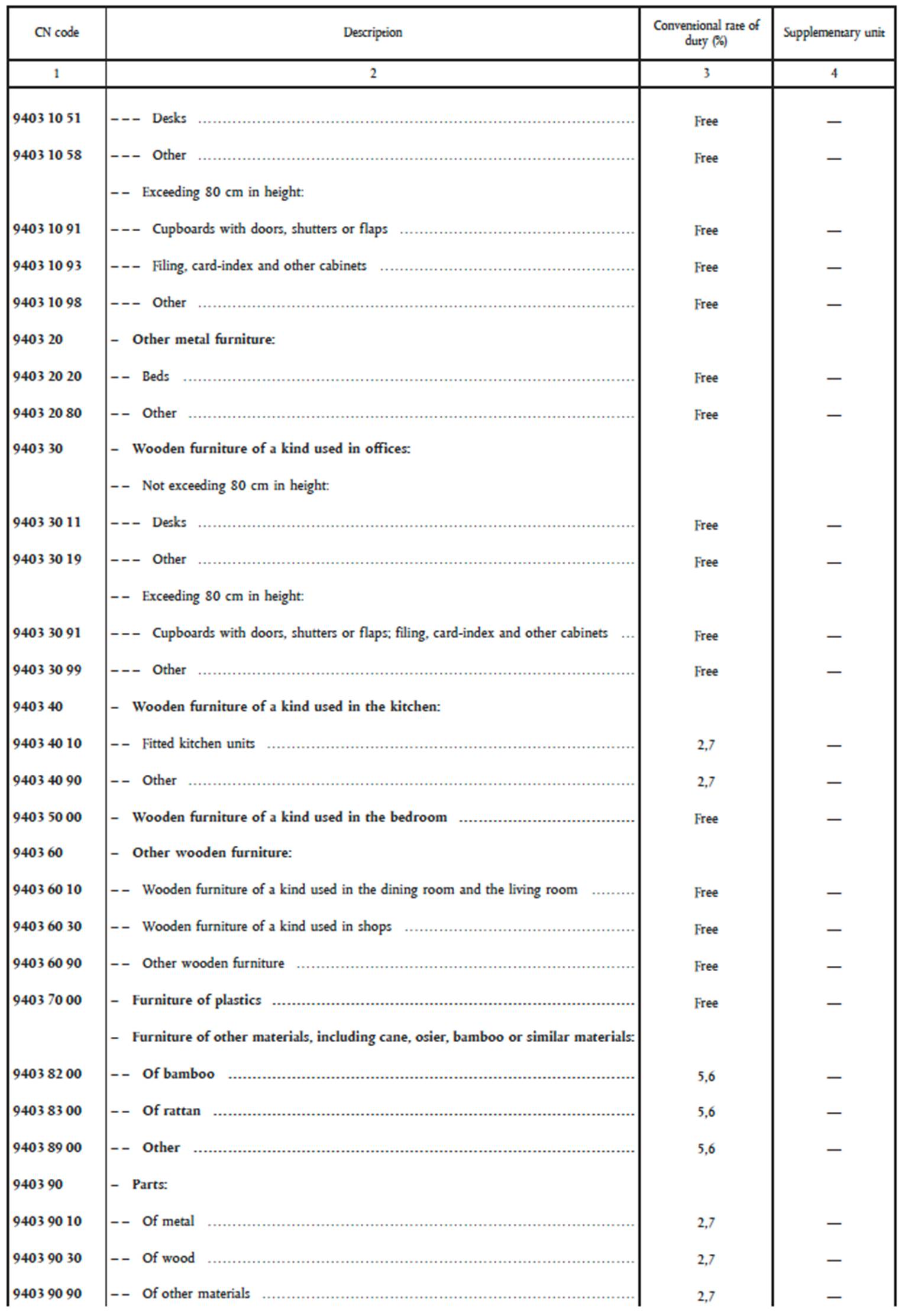

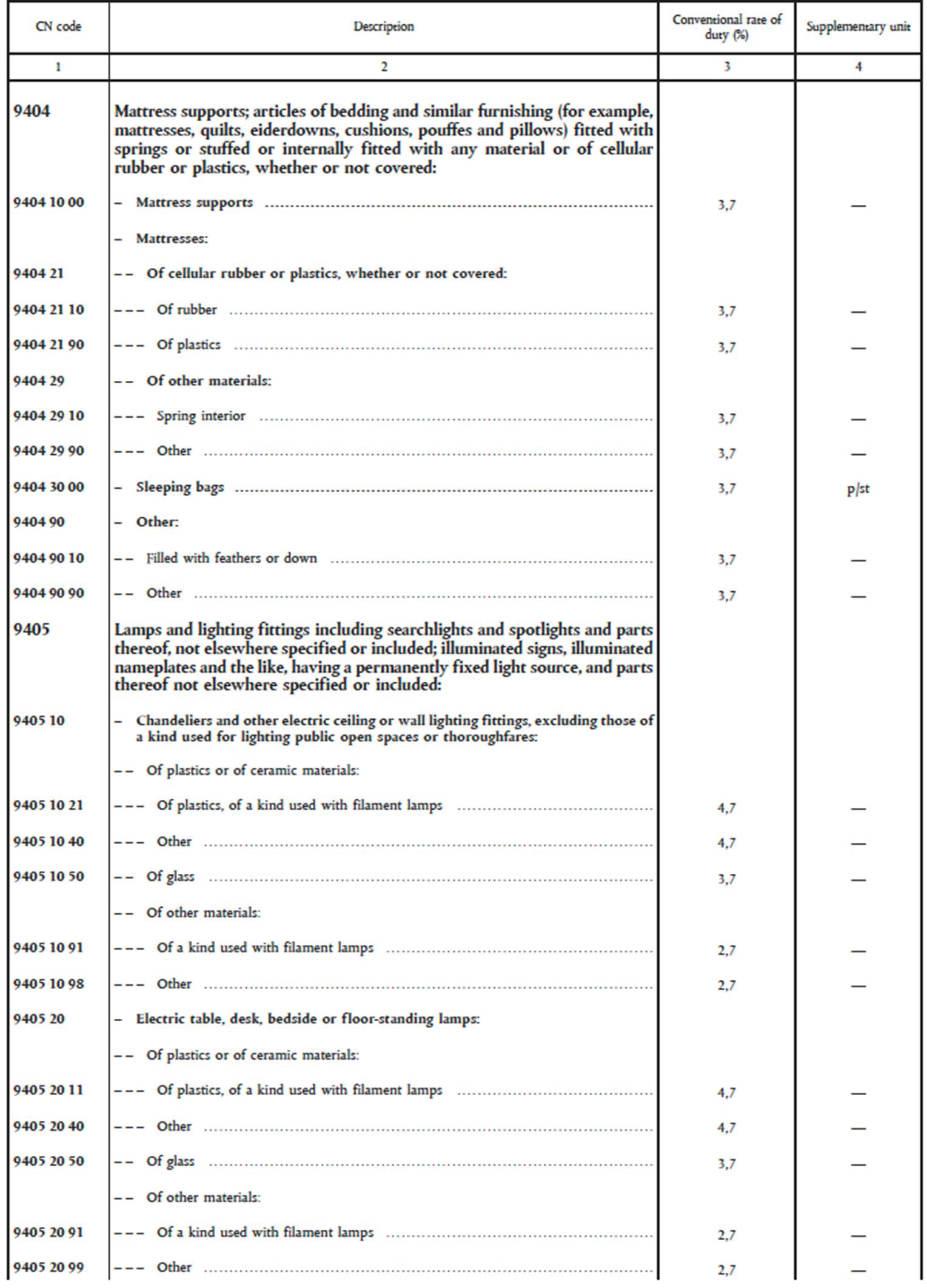

130. That chapter relates to: FURNITURE; BEDDING, MATTRESSES, MATTRESS SUPPORTS, CUSHIONS AND SIMILAR STUFFED FURNISHINGS; LAMPS AND LIGHTING FITTINGS, NOT ELSEWHERE SPECIFIED OR INCLUDED; ILLUMINATED SIGNS, ILLUMINATED NAMEPLATES AND THE LIKE; PREFABRICATED BUILDINGS.

131. As will be recalled, the specific code for the RBS in this appeal was previously 9403 2080 00 and applied across the Customs Union until at least 30 August 2018. This is described as ‘other metal furniture’ in the CN and has a duty rate of 0%.

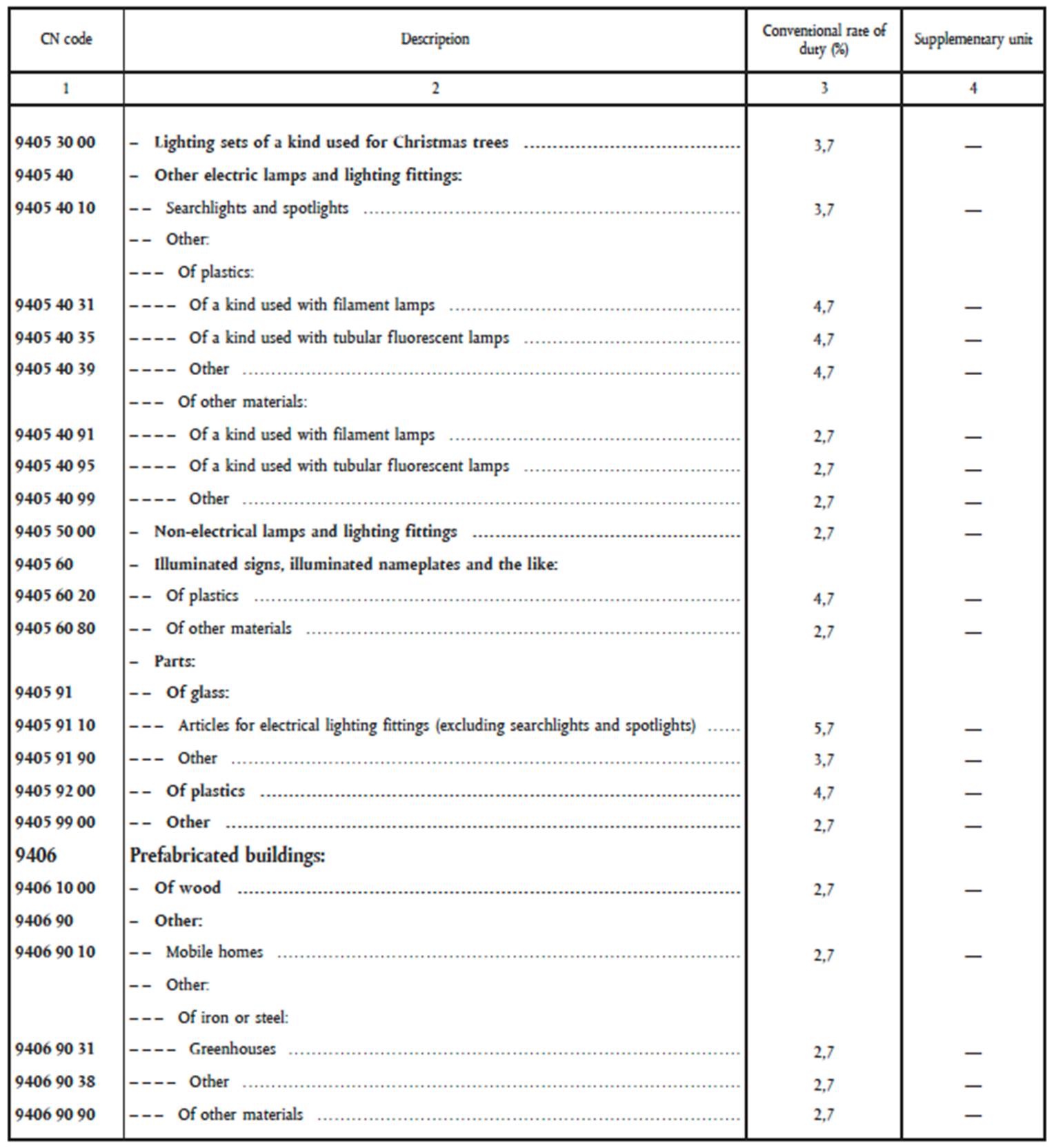

132. The CN for Chapter 94 is produced at Annex 2.

133. As we have said, the CNEN promulgated on 30 August 2018 is produced at Annex 1. The essential text was to advise that the commodity code 9403 2080 00 did not include “information displays” such as “street boards” or “roll-ups” and they should be classified where they are more specifically included. Instead, where the essential characteristic was that of an aluminium frame, the commodity code should begin 7616.

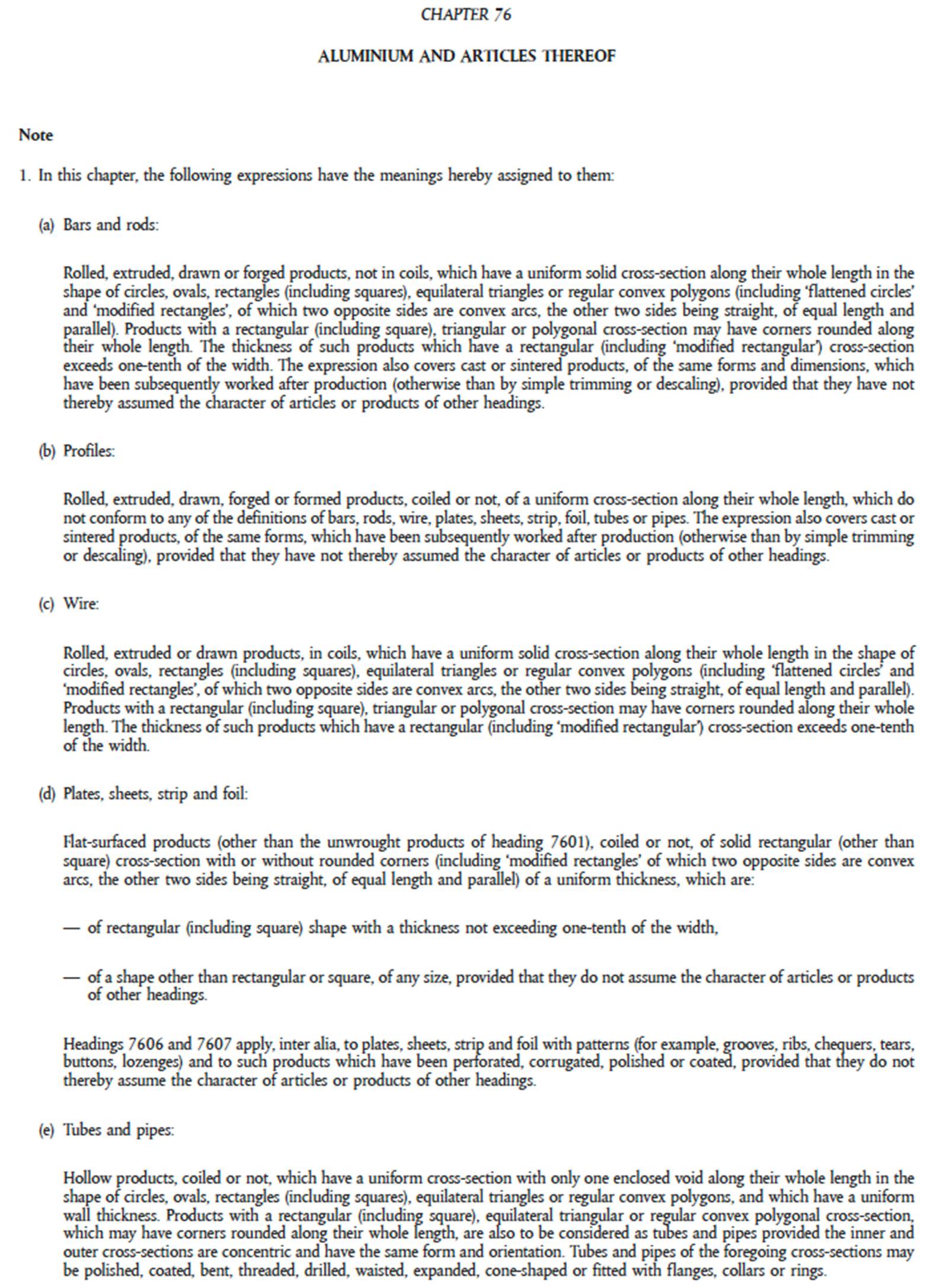

134. There are notes to chapter 94 (as we have set out in full in Annex 2). They state, in material part:

“1. This chapter does not cover:

(a) - (c) …

(d) parts of general use as defined in note 2 to Section XV, of base metal (Section XV), or similar goods of plastics (Chapter 39), or safes of heading 8303;

(e) - (m) …

2. The articles (other than parts) referred to in headings 9401 to 9403 are to be classified in those headings only if they are designed for placing on the floor or ground.

The following are, however, to be classified in the headings mentioned above, even if they are designed to be hung, to be fixed to the wall or to stand one on the other:

(a) cupboards, bookcases, other shelved furniture (including single shelves presented with supports for fixing them to the wall) and unit furniture;

(b) seats and beds.

3. (A) In headings 9401 to 9403 references to parts of goods do not include references to sheets or slabs (whether or not cut to shape but not combined with other parts) of glass (including mirrors), marble or other stone or of any other material referred to in Chapter 68 or 69.

…”

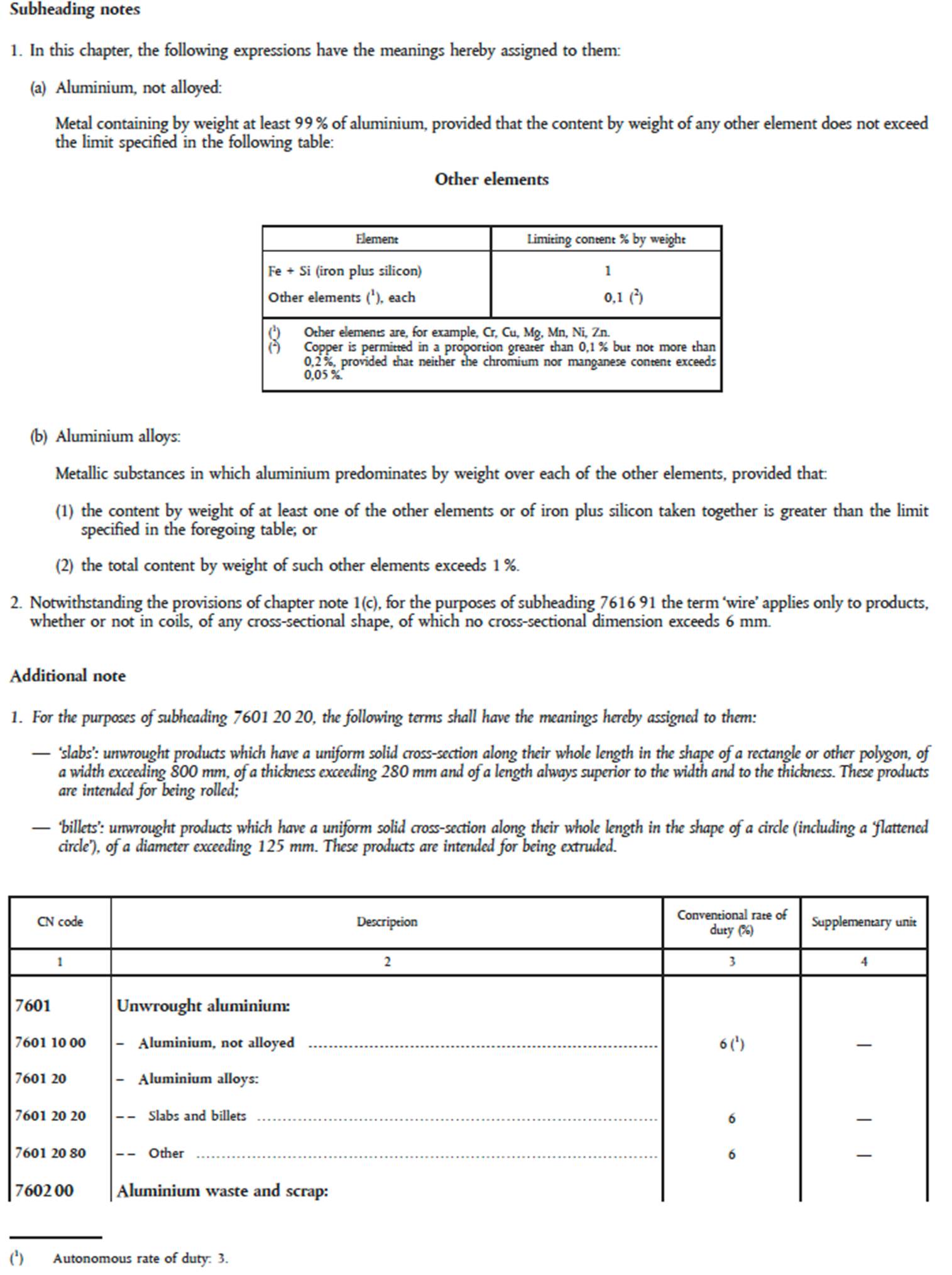

135. Both parties referred us to the HSEN published by the Customs Cooperation Council for Chapter 94 where there is a definition of furniture. That states, for the purposes of that chapter, furniture means:

“(A) Any “movable” articles (not included under more specific headings of the Nomenclature), which have the essential characteristic that they are constructed for placing on the floor or ground, and which are used, mainly with a utilitarian purpose, to equip private dwellings, hotels, theatres, cinemas, offices, churches, schools, cafes, restaurants, laboratories, hospitals, dentists’ surgeries, etc., or ships, aircraft, railway coaches, motor vehicles, caravan-trailers or similar means of transport. (It should be noted that, for the purposes of this Chapter, articles are considered to be “movable” furniture even if they are designed for bolting, etc., to the floor, e.g. chairs for use on ships. Similar articles (seats, chairs, etc.) for use in gardens, squares, promenades, etc., are also included in this category.

(B) The following:

(i) Cupboards, bookcases, other shelved furniture (including single shelves presented with supports for fixing them to the wall) and unit furniture, designed to be hung, to be fixed to the wall or to stand one on the other or side by side, for holding various objects or articles (books, crockery, kitchen utensils, glassware, linen, medicaments, toilet articles, radio or television receivers, ornaments etc.) and separately presented elements of unit furniture.

(ii) Seats or beds designed to be hung or fixed to the wall.

Except for the goods referred to in subparagraph (B) above, the term “furniture” does not apply to articles used as furniture but designed for placing on other furniture or shelves or for hanging on walls or from the ceiling.

It therefore follows that this Chapter does not cover other wall fixtures such as coat, hat and similar racks, key racks, clothes-brush hangers and newspaper racks, nor furnishing such as radiator screens. Similarly, this Chapter excludes the following types of goods not designed for placing on the floor: small articles of cabinet-work and and small furnishing goods of wood (heading 44.20) and office equipment (e.g. sorting boxes, paper trays) of plastics or of base metals (heading 39.26 or 83.04).

However, equipment (cupboards, radiator screens, etc.) built-in or designed to be built-in, presented at the same time as the prefabricated buildings of heading 94.06 and forming an integral part thereof, remain classified in that heading.

Headings 94.01 to 94.03 cover articles of furniture of any material (wood, osier, bamboo, cane, plastics, base metals, glass, leather, stone, ceramics etc.). Such furniture remains in these headings whether or not stuffed or covered, with worked or unworked surfaces, carved, inlaid, decoratively painted, fitted with mirrors or other glass fitments, or on castors etc.”

(emphasis in original)

136. Thereafter, there is remarkably little authority on what furniture is. The combined researches of the advocates, after a request by the Tribunal, have located three of relevance that contain some principle.

137. In Skatteministeriet v Imexpo Trading A/S (C-379/02) the CJEU determined that plastic chairmats were furniture without any wider analysis of what furniture was, save that the HSEN to chapter 94 was relied upon.

138. In Clear Display Ltd v HMRC (TC/2020/3587) (7 January 2022) (‘Clear Display’) this Tribunal, differently constituted, held that the lockable frames in that case were not furniture. Having set out in a table the CN classifications the Tribunal said:

21. It seems to us that whilst things such as street lamps may be said to furnish a street or be street furniture, they are not, in the ordinary use of the word, “furniture”. In the heading of Chapter 94 a colon follows the word “furniture” –

“Furniture: bedding, mattress supports, cushion and similar stuffed furnishings”,

and there follows a semicolon before the list recommences with “lamps and lighting fittings…”. That indicates to us that the word “furniture” is not to be read broadly but is intended to have a meaning consistent with the items which follow it and so confined to items which furnish a domestic room, an office or possibly a garden. On this construction of the Chapter heading, the Locking Frames do not fall within any heading of the Chapter.”

139. The Tribunal went on to find that the CNEN that we are in large part concerned with supported the interpretation in that case that the product was not furniture (together with several other reasons that do not need to detain us).

140. The problem is that as it applies in the case the CN we are considering (published as we have said in October 2017 and October 2018) is headed as we have already set out: FURNITURE; BEDDING, MATTRESSES, MATTRESS SUPPORTS, CUSHIONS AND SIMILAR STUFFED FURNISHINGS; LAMPS AND LIGHTING FITTINGS, NOT ELSEWHERE SPECIFIED OR INCLUDED; ILLUMINATED SIGNS, ILLUMINATED NAMEPLATES AND THE LIKE; PREFABRICATED BUILDINGS.

141. It will be noted that ‘Furniture’ is followed by a semi-colon, not a colon. As a result, whatever the position the Tribunal found itself in in Clear Display, we do not derive any assistance from that case.

142. Finally, in PR Pet BV v Inspecteur van de Belastingdienst (C-24/22) the CJEU determined that cat scratching posts were not furniture. In passages containing principle, they said:

“56. It must therefore be held that the goods falling under heading 9403 of the CN have the common characteristic of being intended for furnishing offices, kitchens, bedrooms, dining rooms, living rooms or shops. Such places have the common feature of being dedicated to occupation by humans.