11. In the event, I did not hear or determine either application before the end of the trial. The timetable was extremely tight and in the course of oral Closing Submissions Mr Hugo Cuddigan KC, Lufthansa's leading counsel, agreed that I should read all of the documents de bene esse and then decide what weight I should attach to them. I am grateful to him for that concession which has made my task considerably easier. Having considered those documents and determined the issues to which they are relevant, I extend time for the service of both the Second and Third CEA Notices and I give permission to the Defendants to rely on the documents referred to in each notice. I briefly express my reasons for doing so:

(1) Lufthansa objected to five documents relating to the transfer of assets to Astronics on the basis that the Defendants had not disclosed them at all in these proceedings and that it was prejudiced because they had been produced after Mr Jouper had given evidence in relation to that issue. I accept that these documents were disclosed very late. But it would have been unfair to Mr Jouper to exclude them because they confirmed his evidence and resolved an ambiguity in his favour.

(2) Further, the documents speak for themselves and a number of them are public documents. It is difficult to see what questions Mr Cuddigan would have been able to put either to Mr Jouper or to a witness who was personally involved in the negotiations for the sale of the relevant business which would have cast any doubt on their contents. Indeed, he could have applied to recall Mr Jouper to deal with them if he had wished to and I would have permitted him to do so.

(3) But in any event, there is no prejudice to Lufthansa. Although I have determined the specific factual issue to which these documents went in the Defendants' favour, I have determined the overall issue in favour of Lufthansa. Moreover, I am far from satisfied that Lufthansa would have had to give credit for a substantial amount or that this issue would have had a significant effect on the ultimate outcome of the Account.

(4) Lufthansa accepted that I had a very broad discretion to permit late hearsay notices but objected to the Defendants relying on the remaining documents for the truth of their contents on the basis that the CEA Notices were served "hopelessly out of time" and Lufthansa had been prejudiced for very similar reasons.

(5) I reject those submissions. I effectively extended time for the service of CEA notices until 13 September 2024 and I am not satisfied that Lufthansa suffered any real prejudice as a consequence of the late notification to Opus to include the relevant documents in the trial bundle. Further, there was no obligation on the Defendants to put any of the documents to Mr Mosebach given that he chose not to give any evidence about the relevant meetings and the documents were put to Mr Jürgen Repenning, the witness who chose to give evidence about this issue.

(6) But in any event, there was no prejudice to Lufthansa in relation to these documents either. Minutes are usually the best evidence of important meetings and it would have been very difficult for Lufthansa to ask me to make findings of fact about what took place at those meetings whilst at the same time resisting disclosure of the minutes. Furthermore, the factual issue between the parties was very limited indeed and, although I accepted the minutes of the relevant meetings as accurate (contrary to Lufthansa's submission), I decided the overall question of factual causation in Lufthansa's favour.

II. Background

A. The EmPower DC

(1) The first ISPS

19. Mr Jouper's evidence was that there was no FAA guidance in place for in-seat power when Olin developed the EmPower DC system and that he and Mr Carl Lund, Astronics' DER, worked together to comply with the FAA's general safety guidance and that he and Mr Darrell Hambley (also of Olin) wrote an initial draft of a detailed memorandum on in-seat power which the FAA modified and adopted. On 6 June 1996 the FAA published that draft guidance under the heading "Guidance Regarding the Installation of In-Seat Power Supply Systems (ISPSS) for Portable Electronic Devices (PED)" addressed to "All Aircraft Certification Offices". It stated as follows:

"The Seattle Aircraft Certification Office has recently been approached by several applicants seeking FAA approval for the installation of systems intended for use by passengers to provide electrical power to portable electronic devices. The in-seat power supply systems are being proposed for installation in transport category airplanes. In consideration of the applicant's proposals, the position of the Transport Airplane Directorate on this subject was requested. The intent of this memorandum is to distribute that position to all aircraft certification offices. The FAA Transport Airplane Directorate advises all aircraft certification offices that for the approval of those power supply systems which connect on-board aircraft electrical power/systems to passenger provided carry-on devices, the following conditions must be met:

1) The in-seat power supply system must be designed to provide for adequate circuit protection against system overloads, smoke and fire hazards resulting from intentional or unintentional system shorts, faults, etc., including children inserting thin metal objects into the socket or liquids being split into the socket.

2) Each system output must employ RF filtering to protect critical and essential level aircraft systems from radiated and/or conducted electromagnetic interference (EMI). Also, the manufacturer must ensure isolation of the aircraft electrical system bus from any electrical noise created by connected portable electronic devices or by the ISPSS itself.

3) A clearly labeled and conspicuous means method (on/off switch) of deactivating the PED ISPSS must be provided for the flight crew. This disabling feature shall be available at all times and must allow for the immediate disconnection of all seat outlets. Use of circuit breakers for this means is not acceptable. Also, a description of the flight crew station control feature and its operation must be contained in the Airplane Flight Manual (AFM). Note: Additional switches may be provided for the cabin crew.

4) Occupants shall be protected against the hazards of electrical shock. Applicants must submit substantiation of non-hazard to passengers for proposed voltages. Irrespective of substantiation, voltages appearing at passenger-accessible electrical power outlets shall not exceed 24 volts.

5) System Power Limitations - Applications must submit substantiation of non-hazard to passengers for proposed maximum power. Irrespective of substantiation, maximum power available at each seat outlet shall be limited to 100 watts (4.17 amps @ 24 volts).

6) Conducted/Radiated electromagnetic capability (EMC) evaluation of the in-seat power supply system shall be accomplished with maximum load at each passenger outlet."

29. On 24 June 1997 the FAA published a revised memorandum headed "Revised Guidance Regarding the Installation of In-Seat Power Supply Systems (ISPSS) for Portable Electronic Devices (PED)" (the "1997 Memorandum"). It involved no change of policy, identified the same hazards as before and it still prohibited the use of higher voltage AC power. Conditions 1, 4 and 5 were in the same or nearly the same form as the 1996 Memorandum although they were now Conditions a., d., and f.:

"a. The in-seat power supply system must be designed to provide circuit protection against system overloads, smoke and fire hazards resulting from intentional or unintentional system shorts, faults, etc. (e.g., including spilling liquids in the sockets and children inserting thin metal objects into the sockets)."

"d. Occupants shall be protected against the hazards of electrical shock. Applicants must submit substantiation of non-hazard to passengers for all proposed voltages. Substantiation must include system requirements which eliminate the risk of shock.

e. To provide for a power connection from the aircraft ISPSS to the portable electronic device, a special adapter shall be required for all connected PED's to operate. The special adapter will have the following characteristic -- it must have a mating connector that will plug into a unique connector on the aircraft side which cannot be mistaken for, and is not compatible with, a conventional duplex alternating current (AC) outlet.

f. System Power Limitations -- Applicants must submit substantiation of non-hazard to passengers for proposed maximum power. Regardless of substantiation, maximum power available at each seat outlet shall be limited to 100 watts."

(3) The JAA Draft Policy

30. On 13 May 1998 the JAA also produced a draft policy (the "JAA Draft Policy"). It stated that it was based on the 1997 Memorandum and that differences between the two texts were indicated by underlining (in accordance with normal JAA practice). It also contained explanatory text in italics. The JAA Policy set out Conditions a, d and e (above) together with the following addition and commentary:

"a. The in-seat power supply system must be designed to provide circuit protection against system overloads, smoke and fire hazards resulting from intentional or unintentional system shorts, faults, etc. (e.g., including spilling liquids in the sockets and children inserting thin metal objects into the sockets). (ref. JAR 25.869(a), 25.1353(d), 25.1357.)"

"d. Occupants shall be protected against the hazards of electrical shock. Applicants must submit substantiation of non-hazard to passengers for all proposed voltages. Substantiation must include system requirements which eliminate the risk of shock (ref JAR 25X1360(a).) The use of low DC output voltage (below 50 volts) is strongly recommended for that purpose.

Reason for proposed change: It is JAA belief that use of standard voltages such as 110V/220V is not appropriate, due to both the potential passenger safety risks and also the "facility" to use "strange" PEDs. The use of low voltage together with specific power connections as described in paragraph e. seems the most appropriate solution for generalised application of the ISPSS concept on JAR-25 aeroplanes.

e. To provide for a power connection from the aeroplane ISPSS to the portable electronic device, a special adapter shall be required for all connected PED's to operate. The special adapter will have the following characteristic -- it must have a mating connector that will plug into a unique connector on the aeroplane side which cannot be mistaken for, and is not compatible with, a conventional duplex alternating current (AC) outlet."

(4) KID

33. On 3 December 1998 KID (which was still then a profit centre or division of another subsidiary of Airbus, DASA) and Lufthansa, entered into an agreement headed "Teaming Agreement" which was in the English language but governed by German law (the "1998 Teaming Agreement"). The Preamble and Articles 1 to 4 provided as follows:

"Preamble

Responding to a permanently increasing market demand for PC Power Outlets in aircraft seats, several companies have introduced in-seat power supply systems to the market. On account of safety regulations issued by the airworthiness authorities (FAA, JAA) these in-seat power supply systems apply only a low l5 VDC output voltage into the seat outlets. KID is one of the suppliers of a 15 VDC system (hereinafter referred to as "Classic System"). LHT has developed a technical concept for a 110 VAC in-seat power-supply system (hereinafter referred to as "Advanced System"). This concept is concentrated mainly upon solutions regarding the necessary safety aspects in order to comply with the safety regulations of the airworthiness authorities, thus facilitating a system certification.

Article 1 Scope

KID will, under its own sole responsibility, introduce the Advanced System to the market. The parties agree that this responsibility comprises the development, the manufacturing, the marketing of, and after-sales support for, the said system. LHT will participate in the revenues resulting from such activities of KID.

[REDACTED]

Article 2 Team Work

In order to arrive at best possible marketing results LHT will render the following support to KID applying its best efforts and to the extent reasonably feasible. LHT will render best efforts to the extent reasonably feasible and at its own cost in actively supporting and cooperating with KID in acquiring the certification for said systems by the Luftfahrt Bundesamt and in case of need by the JAA and FAA. Such support includes for instance advice concerning installation and integration works.

Article 3 System installation

KID undertakes to recommend LHT to any potential buyer as partner for the installation of the systems into the respective aircraft. In principle within this context LHT may offer the following services:

- complete installation of the systems including certification (STC) and complete documentation (full turn key package),

- installation kits,

- certification support.

In such a case LHT will place an offer for such service in its own name, but after consultation with KID, adapted to the individual requirements of the buyer. The placement of the offer and the negotiations resulting therefrom (to be conducted together with KID) will be performed with the express aim to arrive at a commercially attractive over-all offer. In case a potential buyer abstains from choosing the offer of LHT, KID will be free to cooperate with other partners in this respect. LHT will inform KID in due time, if LHT sees no possibility to perform the installation as asked for by the buyer.

Article 4 Promotion

In principle KID will take charge of promotion campaigns at its own costs. However, LHT is also entitled to promotion activities, in which case KID will provide LHT with existing advertising material such as brochures free of charge. Promotion Campaigns conducted by both Parties will be coordinated in advance, especially in respect of contents and costs."

49. The Defendants relied on the fact that the minutes also recorded a wide range of safety features under the agenda item "Fault Protection":

"The different type of faults and fault protection techniques were considered. Initially, there was some confusion over the meaning of Ground Fault Interrupt Protection, Differential Protection and Galvanic Isolation. The definition and meaning for these protection techniques were discussed and agreed to be as follows.

Ground Fault Interrupt Protection:

The protection circuit monitors the current flow in the power input line against the ground potential. If the measured fault current exceeds a certain level, the protection circuit will cut off the power.

Differential Protection:

The protection circuit compares the current flow in the power input and power return lines. If the current differs for more than a certain level, the protection circuit will cut off the power.

Galvanic Isolation:

Use of isolation transformers to isolate the output part of the power outlets

from the main power inputs. The power outlet is effectively floating and should not cause hazardous electric shocks to passengers. This is a technique used in shaver sockets in bathrooms.

The merits of the above techniques were discussed. The general consensus of the meeting was that suitable use of the above methods should address the concerns over short circuit faults (phase to ground fault & phase to phase fault) and shocks to passenger. It was also agreed that the maximum fault current should be limited to 30 mA and the activation time should be less than or equal to 30 mSec. see 'Appendix A' (Attachment 3) for the agreed wording on fault protection issues.

The meeting was inform that KID Systeme uses Differential Protection at each seat out let which will protect the passenger from phase to phase short circuit faults and phase to earth short circuit faults."

51. The revisions to the JAA Draft Policy reflected the decision in principle to permit the installation of ISPSS supplying 110V AC power. Conditions a. and e. were largely unaffected but the additional sentence which had been added to Condition d. recommending DC power had now been removed. An appendix ("Appendix A") had been agreed and added to the draft policy in the following terms:

"Additional Criteria To Be Met for The Installation Of 110V, 60 Hz AC Systems

The following criteria in this appendix should be considered in addition to the material presented in the main guidance document for approval of 110 volt 60 Hz AC ISPSS:

1. The power outlets should be labelled with the output voltage and frequency (110V a.c., 60 Hz) and suitable safety instructions should be provided for the passenger detailing the PED permitted to be used. These instructions should also include the use of the system, its limitations, hazards and the control of airline supplied equipment.

2. Fault Protection.

a) Suitable means of protection should be provided through the use of differential protection and/or galvanic isolation (isolation transformer) to minimise the risk of passenger shock. This is to guard against inadvertent contact with live parts of the system.

If differential protection is utilised, it should have the following characteristics:

Maximum fault current should be limited to 30 mA. Activation time in the event of a differential fault should be less than or equal to 30 mSec. In the event of differential protection circuit failure, output power should be automatically shut down at the outlet.

b) To guard against damage to ISPSS cable assemblies installed in the seat itself, seat mounted ISPSS cable looms should have additional protection means.

3. Indication should be provided to enable cabin crew to detect which outlets are in use.

4. The ISPSS should be automatically deactivated in the event of a rapid decompression of the aircraft.

Note 4 Finally, the use of external audio speakers shall not be permitted with any portable electronic device. All audio must be delivered through headphone[es]."

(9) JAA Certification

54. On 5 October 1999 the FAA agreed to adopt the JAA Draft Policy in its revised form and this agreement was recorded in a revised memorandum (the "1999 Memorandum"). I set out the introduction to the memorandum together with conditions a., d., e. and f. of the "ISPSS Approval Conditions" and Appendix A in full:

"The policy contained in this memorandum has been harmonized between the FAA and a Joint Aviation Authority (JAA) and industry harmonization working group. It should be applied to all transport airplane programs for an acceptable method of compliance with 14 CFR part 25 for in-seat power supply systems (ISPSS) installations.

INTRODUCTION

The following describes conditions that should be met for the approval of ISPSS which connect aircraft electrical power to passenger provided carry-on devices. This policy does not cover the approval of the use of such portable electrical devices (PED's) or any interconnecting means (adapters, cords etc.) used to power such equipment onboard an aircraft. This guidance covers the approval of low voltage (nominal 15V DC) and high voltage (nominal 110V AC, 60 Hz) systems. Nominal output voltages differing from the typical voltage values specified above may also be considered for approval using the guidelines specified in this policy. For guidance on additional criteria to be met for the approval of the high voltage ISPSS, refer to Paragraphs 1), m), and n) of this policy.

This policy is based on the FAA memorandum on the same subject, dated June 24, 1997, issued by the Transport Airplane Directorate. This policy was modified from that in a JAA and FAA study group (DFSG#103) and agreed to on October 5, 1999. Differences from the Draft JAA policy include: references to FAA, CFR, AC (Advisory Circular) etc., rather than JAA, JAR (Joint Aviation Requirements), AMJ (Advisory Material Joint), etc.; the use of American English terminology and some minor clarification and editorial modifications.

ISPSS APPROVAL CONDITIONS

a. The ISPSS should be designed to provide circuit protection against system overloads, smoke and fire hazards resulting from intentional or unintentional system shorts, faults, etc., (e.g., including spilling liquids in the sockets and children inserting thin metal objects into the sockets. Ref. 14 CFR, Sections 25.869, 25.1353, 25.1357).

Output power should not be present at the ISPSS socket until the portable electrical device (PED) connector is correctly mated with the ISPSS socket.

The design of the ISPSS socket installation should be such as to prevent the ingress of fluid into the power sockets.

The hazard to the aircraft occupants of tripping over the PED lead wire should be addressed in the design of the ISPSS connector and installation.

If an automatic overheat protection feature is employed by the ISPSS, then this feature should not be able to be reset in flight.

The ISPSS should be powered from a non-essential power supply (bus) of the aircraft.

In addition, appropriate quantitative and/or qualitative failure analyses of each installed ISPSS should be conducted such that any likely failure condition would not reduce aircraft safety nor endanger the occupants. The analysis should consider the effects of the environment in which any IS PSS equipment is installed, the cooling arrangements and the safety features employed to prevent a fire or overheat condition from being inadvertently created."

"c. Occupants should be protected against the hazards of electrical shock. Applicants should submit substantiation of non-hazard to passengers for all proposed voltages. Substantiation should include system requirements which eliminate the risk of shock."

e. To provide for a power connection from the aircraft ISPSS to a PED, a special adapter should be required for all connected PED's to operate. The special adapter will have the following characteristic: it should have a mating connector that will plug into an ISPSS outlet on the aircraft side that cannot be mistaken for, and is not compatible with, a conventional alternating current (AC) outlet. The intent of this paragraph is, in part, to control the PED's that are connected to the power supply by the selection of a particular connector type if the control of the PED's cannot be effected otherwise (e.g., by equipment features or cabin crew procedures). Automotive sockets (cigarette lighter style) would not be acceptable.

f. ISPSS Power Limitations - Applicants for installation approval should submit substantiation of proposed maximum power as being non-hazardous to passengers. Regardless of the level of substantiation, the maximum power available at each seat outlet should be limited to 100 watts."

ADDITIONAL CRITERIA FOR THE INSTALLATION OF 110V, 60 HZ AC SYSTEMS

The following criteria in this appendix should be considered in addition to the material presented in the main body of this policy for approval of 110 volt 60 Hz AC ISPSS:

1. The power outlets should be labeled with the output voltage and frequency (110V AC, 60 Hz) and suitable safety instructions should be provided for the passenger detailing the PED's permitted to be used. These instructions should also include the use of the system, its limitations, hazards, and the control of airline supplied equipment.

m. Suitable means of protection, such as differential protection and/or galvanic isolation (isolation transformer), should be provided to minimize the risk of passenger shock. This is to guard against inadvertent contact with live parts of the system.

If differential protection is utilized, it should have the following characteristics:

Maximum fault current should be limited to 30 mA. Activation time in the event of a differential fault should be less than or equal to 30 mSec. In the event of differential protection circuit failure, output power should be automatically shut down at the outlet.

The fault protection system should include features for monitoring the health of the fault detection circuits. If a fault is detected, the power to the outlet should be automatically removed. Any automatic reset feature should not be permitted.

n. The ISPSS should be automatically deactivated in the event of a rapid decompression of the aircraft."

"Note 5: Operators should provide suitable safety instructions for the passengers detailing the PED's permitted to be used. These instructions should also include the use of the system, its limitations, hazards and the operation of airline supplied equipment.

The general policy stated in this document is not intended to establish a binding norm; it does not constitute a new regulation and the FAA would not apply or rely upon it as a regulation. Although the FAA retains the discretion not to follow the policy in this document, an Aircraft Certification Office proposing a deviation from this policy should only do so with the concurrence of the Transport Standards Staff, ANM-113. Applicants should expect that the certificating officials will consider this information when making finding of compliance relevant to new certificate actions. Also, as with all advisory material, this statement of policy identifies one means, but not the only means, of compliance."

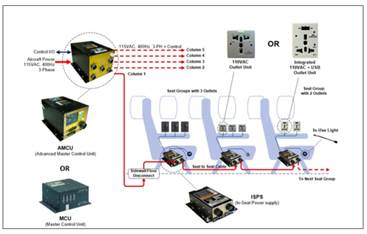

63. One of the documents to which Mr Jouper referred was D1170-226 which was entitled "Safety Features EmPowerTM AC In-Seat Power Supply Part Number 1170-1." The authors of the document described those safety features in section 3.0:

"3.1 DESCRIPTION

The 1170 AC ISPS is a power conversion unit designed to provide an airline passenger access to 60 cycle 110VAC power at the passenger seat. When providing the flying public with access to power, safety features and interlocks must be provided to ensure safe, reliable operation of power and fault tolerance of the power source to ensure passenger and aircraft safety. The ACISPS contains several levels of interlock and safety features to ensure that when the passenger requests power it is available and should a fault condition arise, the power supply will remove power or disable itself under all foreseeable failure modes.

This paper addresses safety at the system level and the seat level. System safety is addressed with the use of the combination of the EMPOWER™ Master Control Unit (MCU) 1067-2, 1170-1 ACISPS and 1171-1 Outlet Unit. These three Line Replaceable Units (LRU) and associated cables make up an extended system of the EMPOWER™ Classic DC system. For information on the EMPOWER™ Classic system refer to System Description Document Dl068-228. This document describes system 1 and 2 for systems with and without the use of an MCU.

SYSTEM LEVEL SAFETY

The EMPOWER™ Classic AC system is designed to meet stringent safety standards as set forth by the FAA and the airframe manufacturers. The AC systems has unique features to compensate for the fact that the system will accept a standard plug. The function of the MCU in the system is to control power enable to the system, interface with the aircraft decompression signal and disable the system during cabin decompression, monitor and control the total power usage of the system, provide overload protection between the MCU and the ACISPS and monitor and report fault conditions via the front panel indicators. The ACISPS provides input current limiting, output current limiting, over voltage protection, under voltage protection, short circuit protection, ground fault protection, thermal sensing and control, EMI filtering from the ACISPS and the Passenger Electronic Device (PED) attached and line voltage isolation from chassis and output

voltage. In addition to the listed safety features, output power is only available when the MCU indicates additional power is available and a user plugs in an appropriate plug and no output faults exist. When an appropriate plug is installed, both contacts of the plug must be inserted with a short time period in order to allow for power to be applied. The timeout is less than 0.1 seconds to ensure that an object inserted in one contact of the outlet will not enable the output to be active.

The outlet assembly provides a shutter type front panel which covers the internal contacts whenever the outlet is not in use, and indicator LED that indicates when power is available and interlock pins providing feedback to the ACISPS whenever a user is plugged in and requesting power."

69. It was also Mr Mosebach's evidence that Airbus, which still controlled KID at the time, chose to settle the dispute and by a settlement agreement dated 27 October 2003 (the "2003 Settlement Agreement") the parties agreed to enter into a new framework agreement to govern the contractual relationship between them and gave mutual releases. In clause 3(e) Airbus and KID also covenanted not to sue GD on the following terms:

"Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this Agreement, the Patent License Agreement, the Existing SFE Framework Agreement or the Framework Agreement (if it is entered), each of Airbus and KID, for itself and for its Affiliates, covenants not to sue or initiate legal action of any kind on any legal theory against GD AES, or its Affiliates, or its or their directors, officers, employees, agents or customers, relating both to (i) any patents owned by Airbus or KID as of the Effective Date, or which Airbus or KID has the right to assert, as of the Effective Date including but not limited to United States Patent No. 6,016,016, and related in any way to power management systems and any continuations, divisions, refiles, reissues or reexaminations of any such patents or the application from which it issued, and any extensions thereof, or any foreign counterparts thereto, and (ii) products marketed as of the Effective Date and made, used, offered for sale, sold, or imported by or on behalf of GD AES or its Affiliates."

70. KID also made certain representations and gave certain warranties about the 1998 Teaming Agreement and, in particular, that Article 6 granted KID an exclusive user's right in return for the payment of royalties. Clause 7(d)(i) provided that the agreement was to be governed by the law of the State of Virginia USA and that all disputes were to be settled by arbitration and clause 7(d)(ii) provided for the exclusive jurisdiction of the Eastern District of Virginia. Clauses 7(h) and 7(i) also provided as follows:

"h. Third-Party Beneficiaries. Except for Article 2, Section 3(e), and Section 4(b), hereof, which are intended to benefit and to be enforceable by any party referred to therein as entitled to a release or forbearance thereunder, nothing in this Agreement, expressed or implied, is intended to confer on any person other than the parties hereto or their respective permitted successors and assigns, any rights, remedies or liabilities under or by reason of this Agreement.

i. Successors and Assigns. Neither this Agreement, nor any of the rights, duties or obligations hereunder, may be assigned (by operation of law or otherwise) by the parties hereto without the prior written consent of all other parties hereto, which consent shall not be unreasonably withheld or delayed; provided, however, that each party shall be allowed to assign this Agreement without consent in connection with a sale or transfer of all or substantially all of such party's assets (or, in the case of GD ABS, all or substantially all of the assets relating to its Airborne Electronic Systems group). This Agreement shall be binding upon, and inure to the benefit of, the parties hereto and their respective permitted successors and assigns (and any party referred to in Article 2 or Section 3(e) hereof as entitled to a release or forbearance thereunder). Any attempt by a party to assign this Agreement, or any of the rights, duties or obligations hereunder, other than as permitted by this Section 7(i) shall be null and void."

D. The EmPower Fusion

77. Mr Jouper's evidence was that to obtain certification Astronics submitted 18 key documents to the FAA, a number of which Mr Acland explored with Mr Repenning. Astronics dealt with Condition a. of the 1999 Memorandum in D1191-202 which was entitled "Response to FAA/JAA Transport Airline Directorate for PED Power Systems EmPower AC In-Seat Power Supply (P/N 1191-x) and Outlet Unit (P/N 1235-x-x)". Section 4.1 was headed "Protection Against Overloads" and after referring to the specific condition in the 1999 Memorandum, Astronics set out its response in a series of bullet points:

"• The ACISPS (1191-x) has been designed and verified to be tolerant of overloads, short circuits intentional and unintentional.

• Power is not applied to the output until an appropriate plug is inserted into the outlet unit.

• After the plug is inserted into the outlet, the ACISPS delays activation of the power.

• The Outlet Unit contact chambers are isolated from each other such that objects inserted into one chamber cannot internally reach the other chambers.

• The Outlet Unit connection is through the use of a standard duplex style connector that can be pulled free under emergency egress situations.

• The Outlet Unit and ISPS carry the third "ground" pin for PED chassis grounding.

• A dual level thermal limit is used to protect the ACISPS during operation. Level one is self-resetting and if this fails, level two will trip and can only be reset by cycling the input power OFF and then ON.

• The ACISPS includes GFI circuit compliant with UL 943. If GFI is tripped, the 60Hz outputs to PEDs are disabled and power must be removed to reset the GFI circuit.

• Installation designs power the ISPSS systems from non-essential busses.

• For safety features of the ACISPS and the ISPSS system refer to document D1191-207."

78. The second bullet point was a reference to the mating guidance in the 1999 Memorandum and in their Closing Submissions the Defendants accepted that this guidance was met by use of the inserted feature of the Patent. However, they made the point that the document identified numerous other safety features including the GFI circuit in the eighth bullet point (above). Astronics also dealt with Condition c. of the 1999 Memorandum in D1191-202 in section 4.4 headed "Electrical Shock". Again, after referring to the specific condition in the 1999 Memorandum, Astronics set out its response in a series of bullet points:

"• The Outlet Unit is finger proof and designed to power plugs.

• Power on self tests are performed to determine proper state of the outlet unit. If the outlet unit is not in the proper state, power is not applied to the outlet unit.

• The outlet unit contacts are in isolated chambers such that a plug or other device may not touch more than one contact internally to the outlet unit.

• After a valid connection, loss of either contact removes power to the outlet unit.

• Over voltage is monitored and the outlet unit is deactivated if the threshold is reached.

• The ACISPS includes a Ground Fault Interrupt (GFI) circuit to protect the passenger in case of contact with output voltage.

• The third ground pin is carried in the system to isolate the PED chassis.

• The ACISPS monitors all internal power supply voltages to maintain the unit within nominal operating conditions.

• Power is not applied to the output unless an appropriate power plug is installed in the outlet unit noted by simultaneous activation of both contacts.

• For additional safety features, refer to Document D1191-207."

79. Astronics also dealt with Appendix A and the additional criteria in the 1999 Memorandum in D1191-202 in section 5. Astronics set out its response in a series of bullet points under the following headings (and for brevity I have excluded the references to the 1999 Memorandum below each one):

"5.1 POWER OUTLET LABEL

• The ISPSS Outlet Unit is labeled with "110VAC 60Hz" to signify the output voltage and frequency.

• Additional system safety instructions, system utilization and approved devices are the responsibility of the customer or installer.

5.2 SUITABLE MEANS OF PASSENGER PROTECTION

• The Outlet Unit is finger proof and designed to power plugs.

• Power on self tests are performed to determine proper state of the outlet unit. If the outlet unit is not in the proper state, power is not applied to the outlet unit.

• The outlet unit contacts are in isolated chambers such that a plug or other device may not touch more than one contact internally to the outlet unit.

• After a valid connection, loss of either contact removes power to the outlet unit.

• Over voltage is monitored and the outlet unit is deactivated if the threshold is reached.

• The ACISPS includes a Ground Fault Interrupt (GFI) circuit to protect the passenger in case of contact with output voltage. The maximum fault current is limited to less than 6 mA and an activation time of less than 30 mSec.

• The third ground pin is carried in the system to isolate the PED chassis.

• The ACISPS monitors all internal power supply voltages to maintain the unit within nominal operating conditions.

• Power is not applied to the output unless an appropriate power plug is installed in the outlet unit noted by simultaneous activation of both contacts.

• For additional safety features, refer to Document D1191-207.

5.3 AUTOMATIC DECOMPRESSION SHUTDOWN

• Logic-level signal inputs are provided in the ISPSS to allow installation of ON/OFF control by either the flight crew, the cabin crew or external keylines such as DECOMPRESSION.

• Actual implementation of ON/OFF switches are a function of the system installation design. Inputs can be routed directly to the ACISPS (when no MCU is installed) or to the Master Control Unit (MCU). In addition, the control switches can go to relay logic to control power to the input of the MCU or ACISPSs without the use of an MCU. This adds an additional safety margin by completely removing the ISPSS from the power bus.

• This switch is normally controlled by the flight crew and/or cabin crew or as a key line input (i.e., altitude or DECOMPRESSION switch)."

80. A number of these passages refer to D1191-207 which was entitled "Safety System Assessment EmPower AC In-Seat Power Supply Part Number 1191-x and EmPower AC Outlet Unit Part Number 1235-x-x". This document referred to both hardware and software safety features:

"The following safety features are implemented in hardware, designed

to safety Design Assurance Level (DAL) C:

• Input Current Limiting

• Output Current Limiting

• Output Over/Under Voltage Protection

• Short Circuit Protection

• Ground Fault Interrupt

• Over Temperature Thermal Limit

• AC ISPS to PED EMI Filtering

• Watchdog Timer

• Warning Labels on the AC ISPS case

• Voltage level indicator on the AC ISPS case

• ON/OFF control from the MCU and/or Flight Crew and Flight

Attendant switches

• AC OU contacts recessed in isolated, enclosed chambers

• AC OU redundant ground wires"

"The following safety features are implemented in software, designed

to RCTA DO-178B software level D:

• GFI BITE

• Power on Self Test (POST) Checksum

• AC OU Plug-in Detection"

83. Mr Barovsky gave evidence that on 8 September 2003 Boeing issued "D-36440 Standard Cabin Systems Requirements Document Rev. D" ("D-36440") providing specific guidance for ISPSS. It was also his evidence that it did not generally distinguish between DC and AC power although paragraph 5.4.2.4(c) did require that: "For AC systems, the ISPS shall be designed to provide nominal voltage of 115 volts AC at 60 Hz". D-36440 did, however, provide general guidance in relation to the safety of each component. For example, the document set out the following guidance in relation to each individual component:

"5.1.1 Safe LRU Design Commentary

Each LRU must be designed with safety in mind. Safety is generally addressed through a combination of design features and protective devices, analysis of the probability of failure and component reliability, and qualification testing. Protective devices must be designed to operate independently from the normal operation of the LRU. Each protective device must "fail safe," i.e., the hazard is precluded when the device has failed. The reliability of each protective device must be documented in the Safety Analysis (SCSRD section 6.1.5) such that each failure is are adequately addressed based on the severity of its effect and associated probability of occurrence.

Passengers and crew must be protected from electrical shock. If the LRU is designed with a non-conductive case, shock is not an issue. If the LRU operates with voltage(s) less than 30 volts AC or DC and is to be installed in a dry area, shock is also not an issue. If the LRU is to be installed in a wet area, e.g., a galley, then adequate grounding (SCSRD section 7.3.2.4) becomes important. If the LRU operates with more than 30 volts AC or DC and is far from an adequate airplane ground, e.g., installed in the passenger seats, purser work station, or video control center, then one or more protective devices must be provided to remove power."

"6.1.5 LRU Safety Analysis Commentary

A Safety Analysis is required for each LRU to document the details of each potential failure in the LRU and its safety impact. That is, each potential failure must be assessed for its effect on the airplane and occupants as described in the System Safety Analysis (SCSRD section 4.2.8). The analysis must identify and discuss the methodology used to avoid failures that assessed as catastrophic, hazardous, or major. The information may be provided in an individual analysis for each LRU, or all together in one detailed System Safety Analysis for the entire system. The LRU Safety Analysis is intended to address the following hazards as a minimum:

1. A passenger or crew member is shocked.

2. There is arcing in the equipment.

3. Sparks are emitted by the equipment.

4. Smoke is emitted by the equipment.

5. An LRU and/or interconnecting wiring starts on fire.

6. An LRU develops a surface temperature exceeding 204°C.

7. A battery vents.

8. Personal injury occurs due to contact with equipment.

9. Personal injury due to exposure to RF transmissions from a wireless system.

Requirements

a. A Safety Analysis shall be provided for each LRU and cable or wire bundle in accordance with the negotiated Technical Data Delivery Plan (SCSRD section 4.2.1). [CR]"

"6.1.5.2 Over-current and Over-voltage

Commentary

Current levels up to the gauge of the power input connector pin/socket will be provided in Boeing installations unless limitations are noted in the LRU Outline Drawing (SCSRD section 6.1.2). Airplane power is subjected to many transients as defined in SCSRD section 7.3.2. Over-current and over-voltage conditions may result in arcs, sparks, smoke, and/or fire. The following questions illustrate the focus of this portion of the safety analysis. They are not presented as a complete set. The supplier is encouraged to "expand the envelope" of the safety analysis for its LRU as necessary based on superior knowledge of the system design, LRU design, and interconnecting wiring.

1. Are there internal components that are incapable of withstanding the maximum input current or normal/abnormal voltage transients?

2. What design features or protective devices, hardware or software, limit the current to internal components that cannot handle the LRU's maximum input current?

3. What design features or protective devices, hardware or software, prevent the LRU's maximum input current from flowing onto smaller-gauge signal output lines?

4. Can pass-through power lines accept the LRU's maximum input current?

5. What happens if a pass-through power line shorts to ground or multiple lines short to each other "downstream" from the LRU?

6. If there are motors or transformers in the LRU, is there a failure mode where an over-current condition may occur without the pertinent circuit breaker opening?

7. If software is used to contribute to the safety margin provided by design features or protective devices, what RTCA/DO-178B level is it?"

86. Astronics was also required to satisfy TS0010 and TS0011 (above) in order to obtain Airbus approval for the EmPower Fusion system. However, the removal of the shutter and twist mechanism from the 1171 Twist Lock prompted Airbus to raise concerns about the safety of the 1235xx outlet units. Mr Jouper also gave evidence in Jouper 4 that Airbus granted approval for the EmPower Fusion system after discussions with the Airbus Design Office. By email dated 24 March 2004 Mr Gerd Dueser of Airbus wrote to Mr Mike Hettich of Astronics raising a number of questions and by email dated 30 March 2004 Mr Hettich replied embedding his answers in bold in the body of the original email. I set out the questions and answers in full in the same format:

"Mike, last Friday we checked the ISPS 1191 in conjunction with the outlet 1235. Main change to the prevous [sic] AC outlet-design is the missing mechanical children protection device. The remaining electronic protection mechanism does not fufill [sic] the certification aspects and Airbus requirements.

Please see comments below on how the specific items are addressed and overall safety is addressed.

1. There is no device which hinders to insert thin objects.

The intended function of the AC OU is to accept thin metal objects (i.e., power plugs). One needs to look at the ISPS (1191) in -conjunction with the Outlet Unit (1235) as a system. The AC OU as a stand-alone unit does not provide power under any conditions to a passenger. Only when connected to the ISPS and specific operational/ safety conditions have been met will power be provided to the Outlet.

TGM/25/10 does not require a device to block objects from being inserted. The TGM requirements state "a. The in-seat power supply system should be designed to provide circuit protection against system overloads, smoke and fire hazards resulting from intentional or unintentional system shorts, faults, etc. (e. g., including spilling liquids in the sockets and children inserting thin metal objects into the sockets)." The 1191 and 1235 meet these requirements.

Further in TGM the FAA/JAA state "In addition a qualitative failure analysis of each installed in-seat power supply system should be conducted such that any likely failure condition would not reduce aeroplane safety nor endanger the occupants ... " The 1191 and 1235 meet these requirements also.

Please see the detailed analysis in the Preliminary Safety Assessment. Once this Preliminary Safety Assessment is approved by Airbus, GD will complete the detailed FMEA, Safety Assessment, and Fault Tree providing the quantitative data fulfilling this requirement.

2. It was no problem to activate the power output at the outlet by inserting "thin objects".

The timing of the insertion of the plug is monitored. The line and neutral contacts on the power plug must engage the power contact "simultaneously" (within 200 msec currently) and remain mated for greater then one second. The intent of this is to reduce the chance of obtaining power if an inappropriate object is inserted. Airbus and GD personnel know the inter-workings of the Outlet and ISPS. Therefore, we understand how to activate the output power. We are investigating a reduction in the "simultaneous" time to 100-l50mSec.

3. We found also no protection element against ingress of dirt and dust or spilling liquids in the socket.

As long as the AC OU maintains a safe condition when exposed to the ingress of dirt, dust, or spilling liquids, then this is not necessary. Also note that the FAA/JAA, Airbus, and General Dynamics installation documentation require the Outlet to be mounted in a horizontal orientation to avoid the ingress of fluids and other materials. GD has performed a series of liquid tolerance tests and the ISPS and OU operated as expected and remained safe during the tests. These test were run with and without plugs inserted.

4. There is no device which detects if a mating PED plug/connector is attached to the outlet.

A correct making plug is determined as indicated in 2. above.

You might answer that the two micro-contact-mechanism is the answer to 1., 2. and 4. but we think that this is not sufficient [sic]. Please propose an additional feature, similar as you had on your previous design with the mechanical children protection mechanism. This mechanism was also good for answering item 3.

GD and the FAA DERs disagree with the need for a mechanical interlock. Instead, we have a significant number of protection devices and safety features in the ISPS and OU that significantly reduce the exposure to electrical shock and continue to meet the FAA/JAA requirements as well as GD internal requirements for safe products. The ISPSS employs numerous safety features to reduce the risk of electrical shock (finger proof, GFI, sense timing for application of power, disconnect timing for removal of power, OU sense self test at power up, delay prior to application of power, etc.). No additional features are required to meet the certification requirements. In fact, if we employed a mechanical interlock, one must address the failure mode of this device and assume that it has failed. Under this failure condition, it is possible that the potential for shock would be increased since the design would depend on the mechanical features. GD has taken an aggressive approach on the safety features of the system and do not depend on a mechanical device which is prone to failure over time.

Please review revision 2 of the Preliminary System Safety Assessment which addresses each function in detail and provides more detailed explanations.

Another issue is the quality of the already installed electronic protection mechanism. Here we require following improvements:- pls confirm that if someone inserts thin metal objects into the outlet during power off that after power up these outlet is still off.

We have implemented a design change to meet this. The auto-reconnect after power is eliminated.

- the pwr-enable-time-window for simultaneously contact insertion shall be <l00ms (as short as practical [sic] possible)

Currently at 200 msec. Will investigate whether this can be reduced and still provide a reliable connection when a power plug is inserted (i.e., still perform it's intended function).

- the pwr-enable-time until the outlet enables power after a successful

insertion of plug shall be >1s.

We have implemented a design change to meet this. The time is set at approximately 1.25s.

- scenario: the outlet pwr is enabled because two thin objects has been inserted simultaneously [sic]. Then one thin object is removed. Then the detection mechanism must deactivate power as fast as possible. Today the timing seems to be too slow (~500ms)

The design is currently at l00mSec.

As a good practice [sic] we strongly recommend to increase the refresh timing and stabilize frequency for the status LED when it is in amber-mode. Goal is a non-flickering amber-light.

We concur with the flickering observation and are implementing a design change to remove the amber mode.

Requirements

1. TGM-25-10 (certification base):

ISPSS APPROVAL CONDITIONS

a. The in-seat power supply system should be designed to provide circuit protection against system overloads, smoke and fire hazards resulting from intentional or unintentional system shorts, faults, etc. (e.g., including spilling liquids in the sockets and children inserting thin metal objects into the sockets). (ref. JAR 25. 8 69 (a), 25. 1353 ( d), 25.1357.)

Comply.

Output power should not be present at the ISPSS socket until the PED connector is correctly mated with the ISPSS socket.

Comply.

The design of the ISPSS Connector installation should be such as to prevent the ingress of fluid into the power socket as far as is practically possible.

Comply (as far as is practically possible). Outlet Unit mounted in horizontal orientation.

2. Airbus spec. requires

For 110 VAC only: Output power shall be available only if both pins are inserted at the same time and if the matching plug is fully engaged in the outlet unit.

Comply. Definition of fully inserted is within .1" of faceplate.

The OU shall be protected against ingress of liquids and insertion of objects. Faulty safety sensors or connections shall lead to disabling of power at the output.

Comply. Definition of protects means maintain a safe condition."

(6) The 2005 Asset Purchase Agreement

88. Section 2.1 provided that the buyer bought the "Purchased Assets" from the seller (and assumed the "Assumed Liabilities"). Section 2.2 identified all of the assets which fell within this description and section 2.2(a) (v) defined the intellectual property rights included in the sale:

"to the extent used or held for use by the Seller exclusively for the Business, and in each case to the extent legally assignable, all (A) patents, patent applications, trademark registrations and applications, copyright registrations and applications and domain names solely to the extent set forth on Schedule 2.2(a)(v), (B) unregistered trademarks, unregistered trade names, computer software, unregistered copyrights, trade secrets, confidential business information (including formulas, compositions, inventions, manufacturing and production processes and techniques, technical drawings and designs, technical data, customer and supplier data, pricing and cost information) and (C) all rights in, relating to, or for use or exploitation of, "Airborne Electronic Systems" and "AES", and in each case, all associated goodwill, including all rights thereunder, remedies against infringement and rights to protection of interests therein under the Laws of all jurisdictions (collectively, the "Intellectual Property");"

101. Mr Robin Hough, who is the Commodity Manager responsible for managing electrical commodities at Safran, also made a witness statement dated 16 May 2024 in which he gave evidence that IFE and ISPS systems were the only electrical commodities which Safran treated as BFE principally because of their high cost. He also gave evidence that although Safran issued a purchase order for each item for record purposes, it received the Components for the EmPower systems at no cost. He gave the following evidence about title to the Components and the contractual relationship between Safran, Panasonic and its customers:

"20. Though Safran receives BFE such as EmPower components at no cost, Safran will still need to raise a PO against which to receive the BFE into stock and maintain traceability. While it will be Safran's customer who will have contracted with the IFE/EmPower System supplier to supply parts, under that contract Safran will be the shipping address for the PO between the supplier and the customer. Safran will therefore raise a zero-value PO simply to receive the parts.

21. When BFE parts such as EmPower components are received from their supplier, the Safran stores team will deal with putting parts in our stock in a similar way to other items. However, importantly, on the receipt, BFE part numbers will be given an identifying suffix that is unique to the airline supplying the parts to us as BFE. For example, for American Airlines, the parts would be booked as (ABC123)-AA. Air New Zealand has a suffix of "AZ", and so on. Each airline is given a different suffix because these are standard IFE systems and Safran will likely receive the same IFE system from different customers, so we must have a way to assure that the correct IFE system is installed into the correct seats. Airlines may be using the exact same part numbers, so the suffix denotes ownership of the particular part.

22. Regarding title in the BFE parts, Safran does not own the BFE at any stage. They are owned by the customer. I am not aware that title ever transfers to Safran. The suffix shows that the parts are owned by someone else and not to be touched for any other purpose other than installation into that customer's seats."

24. Contracts relating to BFE are made between our business and our customer. Who our customer is, contractually, is not something I get involved with. My understanding is that it can be an airline or Airbus/Boeing. Either way, as far as BFE is concerned, Safran will be supplied it free of charge. There is no contract for the supply of BFE parts between Safran and the BFE supplier.

25. As briefly mentioned above, the only circumstance where we would have a contractual relationship with Astronics or any supplier of a BFE EmPower System is if we lose or break parts supplied to us and have to replace them at our cost. In those circumstances, there is a transactional PO raised and the "battle of the forms" determines whose terms and conditions apply. From memory, we did not have a consistent process in place over the relevant period for issuing further paperwork asserting Safran's terms & conditions of purchase after receipt of a supplier's order acknowledgement, so typically the supplier's terms and conditions would apply.

26. Across suppliers, our relationship with Panasonic ("PAC") and other IFE system suppliers is the same as it historically has been with Astronics. We only place a PO with them in respect of replacement parts, the terms of which will then be governed by either Safran's standard Terms of Purchase or the supplier's standard Terms of Sale."

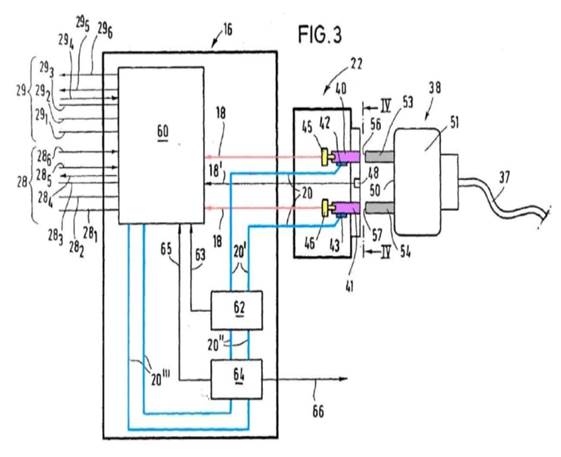

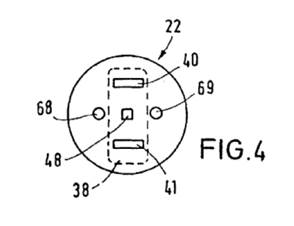

128. Morgan J described the way in which he understood the invention to work in the Liability Judgment by reference to Figures 3 and 4 in the following passage at [36] to [42]:

"36. The recessed contact terminals in the socket (shown in purple, 40, 41) were each designed to receive a pin, and at the end of each recess there was a microswitch (in yellow, 45 and 46). As the plug was pushed in, each pin travelled to the bottom of its recess and on reaching the end it triggered its corresponding microswitch, detecting that the pin was inserted.

37. On the front face of the socket (22) there was an optical infrared reflection sensor (48), which sensed the body of the plug. It comprised an infrared emitting LED and a receiver diode. If the distance between the socket and the plug fell below a certain minimum separation, the radiation emitted from the LED was reflected from the plug and received by the receiver diode.

38. Each of the microswitches was connected via a signal line (18) to the voltage supply device (specifically, to a control and monitoring unit - 60). Each microswitch, when activated, sent a signal from the socket to the voltage supply device. When all signal inputs were triggered (i.e. when both contact pins are inserted far enough to push the microswitches), the supply device detected that a plug has been inserted. The optical sensor was similarly connected to the supply device via a signal line (18'), and when the plug was close enough to reflect the light from the LED, that too could send a signal to the supply device.

39. The control and monitoring unit was connected to the 110V, 60Hz mains supply (29, 28), and had a voltage switch that could apply the high voltage (via supply cables 20).

40. The control and monitoring unit of the supply device also took inputs from a short circuit detector (62) to detect current leakage and provide power limiting of the power supply to approximately 100W to prevent overload of the supply device, and from a line monitoring detector (64) that worked together with the control and monitoring unit to filter interference out of the supply lines.

41. In this way, when the supply device received an input from all the associated sensors and detectors, indicating that each sensing condition was satisfied, it could switch the supply on, allowing high voltage power to flow, via the supply lines (20) to the pins of the plug.

42. Figure 4 (above) showed the face of a socket designed to receive the 2 pins of a US plug (40, 41) or of a European plug (68, 69). The optical sensor (48) was shown at the centre of the socket. There was no hole for the earth pin of a UK plug."

129. As I have stated above, the Patent consisted of a detailed description and seven claims. Claims 1 to 3 were the subject matter of the declaration which Morgan J made in the Liability Order and Claim 2 was held to be valid by the German Courts. Claim 5 was also the subject matter of detailed argument before the judge in the context of the construction of Claim 1. I therefore set out Claims 1 to 7 in full:

"1. A voltage supply apparatus for providing a supply voltage for electric devices (36) in an aeroplane cabin, comprising a socket (22) to which the device (36) is connectable by means of a plug (38) and to which the supply voltage can be applied, the socket (22) comprising a socket detector (45, 46, 48) detecting the presence of a plug (38) inserted in the socket (22), and a supply device (16) being provided remotely from the socket (22) and being connected to the socket (22) via a signal line (18) and via a supply line (20) for the supply voltage, the supply device (16) applying the supply voltage to the socket (22) when the plug detectors (45, 46, 48) indicate the presence of the plug (38) via the signal line (18) to the supply device (16).

characterized in that

the plug detector (45, 46) is formed such as to detect the presence of two contact pins (53, 54) of the plug (38) in the socket (22), and the supply device (16) only applies the supply voltage to the socket (22) if the presence of two contact pins (53, 54) of the plug (38) is detected simultaneously.

2. The voltage supply apparatus according to claim 1, wherein the supply device (16) only applies the supply voltage if a maximum contact time is not exceeded between the detection of the first and the second contact pin (53, 54) of the plug (38).

3. The voltage supply apparatus according to claim 1 or 2, wherein the plug detector comprises mechanical switches (45, 46) activated by the inserted contact pins (53, 54) of the plug (38).

4. The voltage supply apparatus according to one of claims 1 - 3, wherein the plug (22) comprises a casing detector (48) detecting the presence of the plug casing (51) of the plug (38) at the socket (22).

5. The voltage supply apparatus according to claim 4, wherein the casing detector (48) is an optical reflection sensor detecting a minimum distance of the plug casing (51) to the socket (22).

6. The voltage supply apparatus according to claim 4 or 5, wherein the supply device (16) applies the supply voltage to the socket (22) only if the plug detector (45, 46) indicates the presence of the contact pins (53, 54) and the casing detector (48) indicates the presence of the plug casing (51).

7. The voltage supply apparatus according to one of claims 1-6, wherein a plurality of supply devices (16) and a central voltage source (30) are provided for the voltage supply of the supply devices (16), the voltage source (30) being able to be deactivated by a control signal."

141. The importance of Neuenschwander to the issues which I have to decide is that it framed the dispute over the insertion test. If the Defendants were right and the insertion test did not require full insertion then, so the Defendants argued, it was not novel over Neuenschwander. The dispute was also relevant to an argument which the Defendants advanced in relation to Figure 4 (above). They argued that the insertion test only required partial insertion because Figure 4 contemplated micro-switches at the sides rather than the bottom of the plug holes:

"72. Mr Acland drew attention to Figure 4. Figure 4 is described in paragraph [0032] of the description in the Patent. That paragraph refers to the location of the microswitches for the plug detector in a way which is consistent with the other parts of the description whereby the microswitches are at the bottom of the holes for receiving the pins of the plug. However, paragraph [0032] goes on to refer to the possibility that the

pairs of plug holes (US and European) might be arranged so that they are not at right angles to each other (as shown in Figure 4) but overlay each other. With that possibility, paragraph [0032] states that the microswitches are to be arranged to the sides of the plug holes. There is no drawing dealing with this possibility which shows where precisely the microswitches should be placed.

73. Mr Acland suggested that if, for the purposes of this possibility, the microswitches were placed on the sides of the plug holes but not at the bottom of the plug holes, then a plug would be detected when it was not fully inserted. The suggestion then seemed to be that when I come to construe claim 1, which refers to an arrangement which appears to require full plug insertion, I should reconsider what it means in order to accommodate the possibility referred to in paragraph [0032], but not illustrated, which might involve switches which are not at the bottoms of the plug holes. It then appears to be said that I should then hold that claim 1 permits the microswitches to be at the bottom of the plug holes or somewhere else on the sides of the plug holes.

74. Mr Acland's submission based on paragraph [0032] involves reading claim 1 in a way which is wider than the language in which it is apparently expressed and which dispenses with the requirement apparently expressed in claim 1 which is that the plug is detected when the pins make contact with microswitches at the bottom of the plug holes. I accept that the possibility which is identified in paragraph [0032] is part of the material which I should consider when I come to construe claim 1 but it is not the only material. I consider that taking the wording of claim 1, with its express cross references to the drawings and taking the other parts of the description and drawings altogether, claim 1 does identify a requirement that the plug is fully inserted in the socket and that is how it should be construed. On that basis, claim 1 and, indeed, the other claims do not appear expressly to deal with the possibility referred to in paragraph [0032]. I was not addressed on the implications of that position as regards

that possibility and I will not deal with it further."

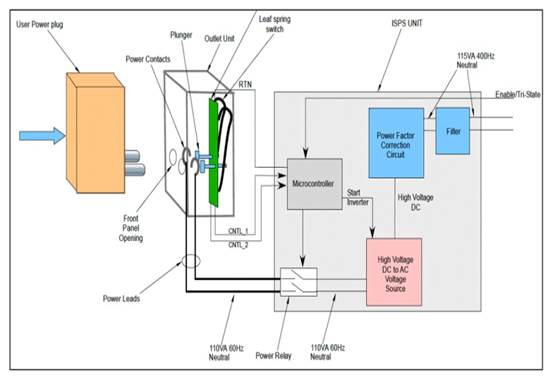

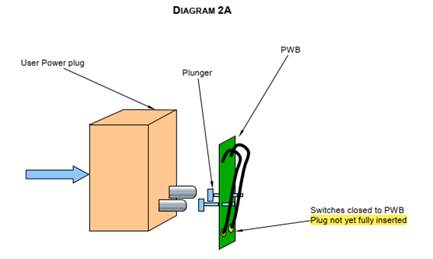

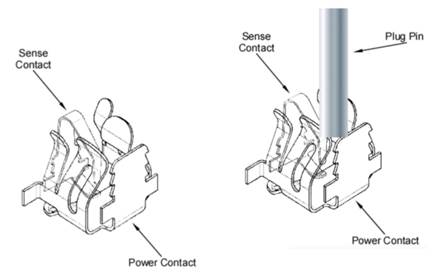

161. Figure 4 shows the plug pin being pushed into the Power and Sense Contacts (which are just behind the Twist Lock faceplate). Section 3 described the operation of the system in the following terms:

"3.2 The 1171 Twist Lock Outlet Unit is a plug socket. It comprises a "female" socket, that is, a housing, which contains two or more holes intended to receive the pins of a "male" plug to which electric devices can be connected. Each of the line and neutral holes in the female socket contains a Sense Contact and a Power Contact as illustrated above.

3.3 Mains power is only available at the Outlet Unit as described below. The presence of a plug in the Outlet Unit is detected using two sensors (the line sensor and the neutral sensor), each comprising a Power Contact and a Sense Contact. As the plug is pushed in, each pin first comes into contact with a Power Contact. On being pushed in slightly further, each pin comes into contact with a Sense Contact, thereby providing an electrical connection between the two Contacts through the plug pin itself. This electrical connection initiates the transmission of a signal to the ISPS Unit microcontroller via CNTL_1 or CNRL_2.

3.4 Upon the microcontroller receiving a signal from either one of the sensors, the ISPS Unit then sets a timer of 50 or 300 milliseconds depending on the model of ISPS Unit. When the timer expires, the ISPS Unit checks whether signals are present from both line and neutral sensors. If this criterion is met, a further 0.5 second timer is set. If both sensors remain engaged throughout the duration of the second timer, the central AC voltage source is engaged, a corresponding output relay is closed and power then flows, via the power cable (labelled "Power Leads" in Figure 1) which is contained within an Interconnect Cable, to the 1171 Twist Lock Outlet Unit and the user's device.

3.5 In the 1171 Twist Lock Outlet Unit design, the Sense Contacts and Power Contacts are located on the side of the holes into which the plug pins are pushed. For all compatible plug types, power is supplied to the1171 Twist Lock Outlet Unit by the ISPS when a portion of the plug pin remains outside the 1171 Twist Lock Outlet Unit."

165. Professor Patrick Wheeler, who is Professor of Power Electronic Systems at Nottingham University and head of the Power Electronics Machines and Control Research Group, gave expert technical evidence on behalf of Lufthansa both at the Liability Trial and on the taking of the Account. In section 6 of his fifth report dated 2 September 2024 ("Wheeler 5") he gave the following evidence about the Twist Lock:

"32. I understand that the Defendants assert that the location of the switches in the hypothetical modified 1171 Twist Lock outlet unit, and the degree of pin insertion required to activate them, would be the same as in the actual 1171 Twist Lock outlet unit. I have been asked therefore to consider the question of equivalents by reference to the actual 1171 Twist Lock outlet units.

33. The 1171 Twist Lock outlet unit is shown in Figures 1 and 2 of the Defendants' 'Particulars - AES 1171 Twist Lock'. It has its detectors arranged to the side of the pin sockets so that it detects the side of the pin, not the end of the pin. I have been asked whether the 1171 Twist Lock achieves substantially the same result as the invention of claim 1, in substantially the same way.

34. In this regard, the result is a safe arrangement for detecting a plug inserted in the socket. The skilled person would consider the key objective of having switches at the bottom of the socket holes was to ensure that the length of pin exposed at the trigger point were kept to a safe level. I have explained that the inventive concept of claim 1 achieves this result through the use of pin detectors which are triggered only once the pin is inserted. An arrangement such as that of the 1171 Twist Lock outlet can achieve this objective. This is because what matters is the pin exposure at the point at which the pin detector is triggered.

35. The question whether the 1171 Twist Lock does in fact achieve the same result will therefore depend on the amount of pin exposure allowed by those outlets in practice. It is apparent that the pin detectors on the 1171 Twist Lock, though on the side of the socket holes, are deep within the socket holes. Jones Day have shown me a table comparing the 1171 Twist Lock with the 1235 outlet. I attach this at Exhibit PWW-31. I understand this to be a document created by AES. I note that AES indicate that with both the 1171 Twist Lock and the 1235 outlet, there is 0.1 inch (i.e. 2.5mm) of pin exposure at the point when power can be supplied. On its face, it is an indication that the 1171 Twist Lock outlet and the 1235 outlet achieve the same result in this respect. In particular, they promote safety by testing for a plug which is almost completely inserted, with the degree of insertion required by both outlets being identical.

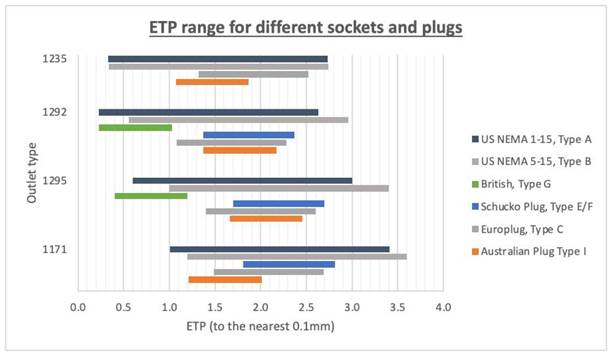

36. I have also been referred to the results of experiments conducted for the purposes of these proceedings by the Defendants, which I attach at Exhibit PWW-32. I understand these have been designed to show the pin exposure at the power trigger point for 1171 Twist Lock outlets and for each of the 12xx outlets which were the subject of the liability trial. These results are shown in the following chart (where 'ETP' refers to Exposure Trigger Point - i.e. the degree of pin exposure at the point at which the power is turned on):..."

169. The ETP Chart was reproduced in both Lufthansa's Opening Trial Skeleton and its Closing Submissions. The Defendants did not challenge it and, indeed, they reproduced the part of it relating to the 1171 outlet in their own Closing Submissions. Professor Stephen Burrow, who is a Professor of Aircraft Systems at Bristol University, gave expert technical evidence on behalf of the Defendants. He was instructed not to address Wheeler 5, section 6 on the basis that it was a matter for legal argument. However, Mr Cuddigan put this section of Professor Wheeler's report to Professor Burrow in order to establish whether there were any technical issues between them:

"Q. I am grateful. What happened next in Professor Wheeler's report is he addressed the question of equivalence of Twist Lock in relation to the switch position issue. Now, that was another section which you were told was legal argument. You've read this part of Professor Wheeler's report, haven't you? A. I have, yes, yes, yes. Q. If, perhaps, we could pull out so we can see how it continues over the page. Is there anything in section 6 which you disagree with as a matter of engineering? A. So I think, just to try and be helpful here, I think perhaps the difference in the legal point is about where you set your test for equivalence. So is the result safety, and that's achieved by detecting full insertion, or is it the result detecting pins, and so on? I think that's why, to that extent, it is a matter for legal argument, I don't think I can offer anything to the court. For me, as I'll try to articulate, whether you detect the end face of the pins or the side face, it does have some consequence on how easy it would be to cope with particularly the difference in the different plug standards, and achieve zero ETP. Q. Yes. That point aside, is there anything that you take issue with in this section of Professor Wheeler's evidence as a matter of engineering expertise? A. How far through? So are we 32, 33, 34 -- Q. Could you go as far as -- as far as 39 {C2/12/13}, please. A. Right, okay. (Pause). So the only thing -- I've got to 35 {C2/12/12}. So in exhibit PWW-31, I believe that is a -- sort of a design target or a design aspiration for them and it does, indeed, quote 0.1 of an inch as the ETP with NEMA sockets. I think, although that was the design target, we've discovered through the experiments that actually there is a bit of variation, that they both don't achieve that, and particularly the 1171 doesn't achieve that aspiration. Q. Yes. It doesn't always achieve it, but it does sometimes? A. Indeed, yes. Yes. So I think in -- I'm just down to the bottom of page 10 at the moment. So in 37 {C2/12/12} Professor Wheeler describes the key safety objective for preventing access by a passenger's fingers to the live pin. I think that's -- it's also a combination of the shape of the plug housing. So although we can talk about the pin exposure, and we imagine the face of the socket as a plane, the shape of the plastic housing around the side will influence whether or not we could say a passenger's fingers might contact with those pins, but I take his point. Q. So the plug shape is part of the solution as well? A. And that is why plug shape is dictated in the standards. Q. Yes. A. And that's partly why travel adapters can never meet the standards, but anyway. Could we move on to the next page, please? (Pause). So I think you see in, sort of, 38 {C2/12/13} where myself and Professor Wheeler differ in our outcomes. So for me, the way the Twist Lock actually detects -- the mechanism is so different that, in my mind, I suggest it doesn't achieve in the same way. But if the test is wider and it doesn't matter about the mechanism, then you can understand you come to a different conclusion. (Pause). And in 39, again, I think it is probably a legal matter, rather than -- Q. It's certainly a mixed -- A. Yes. Q. -- engineering and legal matter, absolutely. So I'm content for you not to engage with that, if you would prefer not to. A. I don't think -- I don't think I have anything to add there."

170. Professor Burrow disagreed with Professor Wheeler that the 1171 Twist Lock made use of the same inventive concept as Claim 1 but considered this to be a legal issue. Subject to this qualification, he accepted all of Professor Wheeler's evidence in the passage which I have set out above and added some useful detail of his own. I make the following findings of fact based on this evidence and the Twist Lock PPD:

(1) I accept Professor Wheeler's evidence and I find that the pin detectors of the 1171 Twist Lock were deep within the socket holes although on the sides of the socket holes rather than at the end of each one. I also accept Professor Wheeler's evidence and I find that the purpose of locating the pin detectors was to ensure that the length of pin exposed at the trigger point was kept at a safe level.

(2) I also find that the purpose of positioning the plug detectors to the side of the plug receptacles or plug holes was to enable the outlet to send a power-on signal for all five compatible plug types, namely, the US NEMA 1-15, the US NEMA 5-15, the Schuko plug, the Europlug and the Australian plug: see the Twist Lock PPD, ¶1.5 and ¶4.3 together with the table immediately below it.

(3) I accept Professor Burrow's evidence in cross-examination and I find that Exhibit PWW-31 contained a design target. I also find that the 1171 Twist Lock and the 1235 outlet were designed to have the same ETP target of 0.1 inch or 2.5 mm when used with a standard US NEMA plug.

(4) Professor Burrow did not challenge the accuracy of the ETP Chart and the Defendants relied on part of it themselves. I therefore find that the ETP Chart was an accurate record of the repeat experiments and that those experiments established that the range of ETPs for a single example of each of the 12xx series, for a single example of each type of plug was between 0.20 mm and 2.95 mm (depending on the outlet and the plug).

(5) I also find that the ETP range for a single example of the 1171 Twist lock was between 1.00 mm and 3.60 mm (depending on the plug) and that:

(a) The maximum ETP for a single example of the US NEMA 1-15 Type A plug was 3.4 mm.

(b) The maximum ETP for a single example of the US NEMA 5-15 Type B plug was 3.60 mm.

(c) The ETP range of two examples of the 12xx series, namely, the 1235 outlet and the 1295 outlet was 0.5 mm to 2.9 mm.

(d) There was an overlap of 1.9 mm in the ETP range of the examples of the 1171 Twist Lock outlet and the 12xx series outlets.